AUSTIN, Texas — With the end of the U.S. Civil War, 3.5 million enslaved Black Americans would be set free.

Even though President Abraham Lincoln’s "Emancipation Proclamation," which would eventually lead to the end of slavery in the Confederacy, had been issued in 1862, it wasn’t until June 19, 1865 – the date now known as Juneteenth – that word reached Texas, when Union Gen. Gordon Granger announced the order to the people of Galveston.

As the news spread across Texas, 250,000 formerly enslaved people in the state faced the reality of having to figure out how to make a home, put food on the table and create a better future for their families.

But in that period after the Civil War, matters could not have been more difficult for them. Confederate states like Texas were determined that ex-slaves would neither be truly free nor equal. The Ku Klux Klan and other white terror organizations used lynching and white riots against Black Texans. Jim Crow Laws and Black Codes were the frameworks for an entrenched system of white supremacy and racial segregation.

By 1870, Black residents made up 30% of Texas’s entire population, which was estimated to be 840,000. But there had been so much violence against them, many would travel to bigger cities like Austin, Houston and Dallas where federal troops could offer protection.

Many Black residents in Central Texas would settle in what were known as “freedman’s towns.” Even though so-called “free Blacks” had occupied Austin since the early 1800s, the influx of newly freed slaves led to the creation of 15 separate enclaves where they lived near one another and established their own businesses, schools and churches.

There was Clarksville, established by Charles Clark in 1871, home to hundreds of freed slaves. Located just west of the MoPac Expressway between West Sixth and West 10th streets, the Clarksville neighborhood is now known as a place for pricey homes and long-established businesses.

There was Wheatville, formed by James Wheat in 1869 and located in part of an area now known as the University of Texas at Austin's West Campus neighborhood. The first Black newspaper published west of the Mississippi after the Civil War was compiled, edited and printed there. Its former headquarters still exists in a building on San Gabriel Street that’s surrounded by high-rise UT student condos.

In 1928, Austin City Hall developed a plan that would force Black Americans out of their homes in Wheatville, Clarksville and other freedman’s towns scattered around the city, and into a single community located on the east side of town. To ensure that people would move, City officials warned residents that it would not provide paved roads or sewer lines in the freedman’s towns.

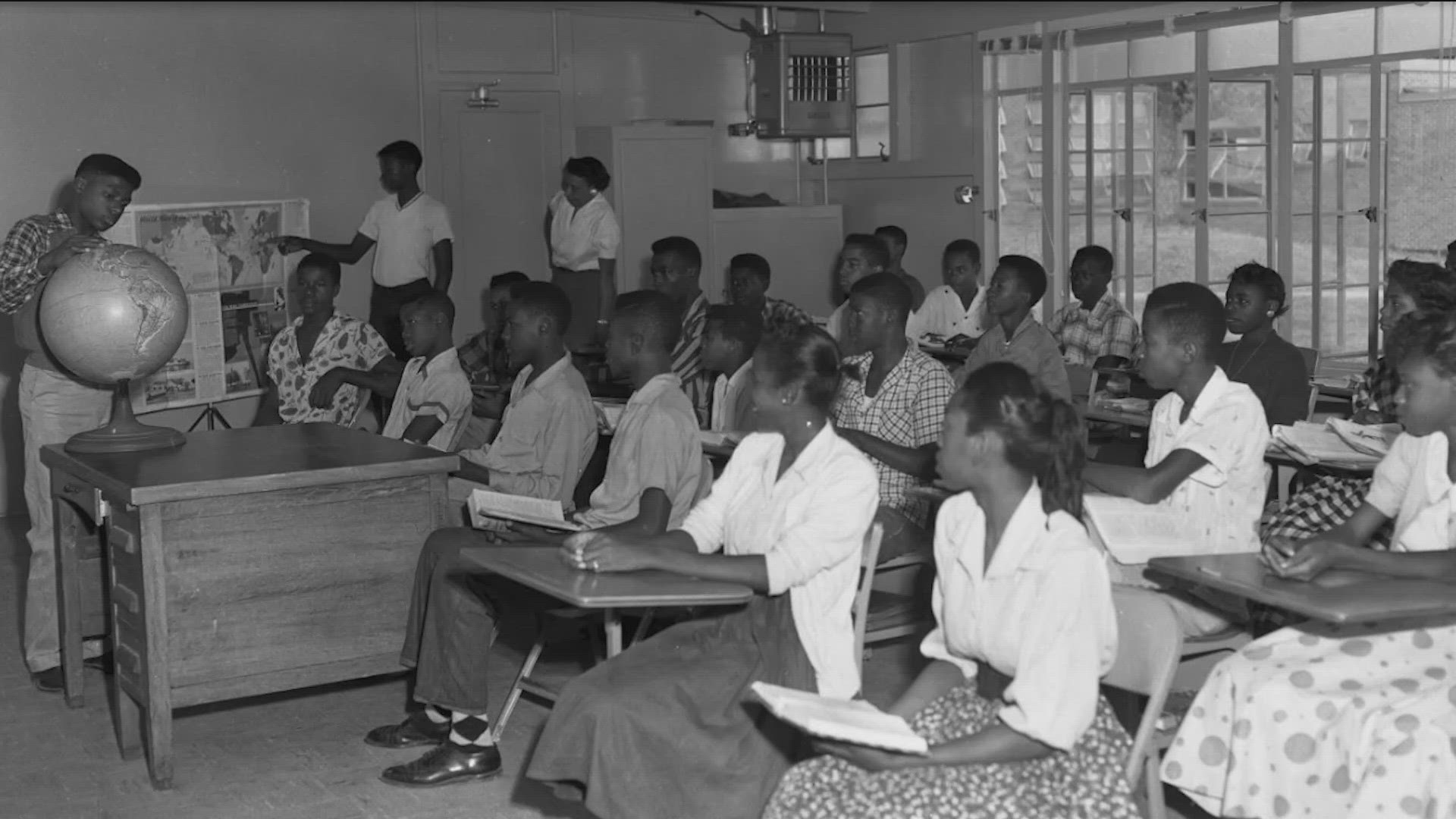

Black Austinites were forced to settle into what the city planners called the “Negro District.” Though the City did help to provide schools, parks and swimming pools, many were substandard.

As East Austin developed into a growing Black neighborhood, East 11th Street would become the focus of a thriving business community. Nearby Tillotson College would offer new opportunities for advanced education. It eventually merged with Huston College to become the higher learning institute we know today as Huston-Tillotson University.

From the 1940s onward, East Austin developed into a heart of Black cultural life and education, a community that shared a common bond through worship at the abundant neighborhood churches.

Yet, for Black Austinites, having a place in the political process was virtually nonexistent. They were shut out of developing public policy or holding elected offices. Making conditions worse, East Austin was considered an industrial zone and in 1948, several large oil companies began building petroleum tank farms that, over time, caused ground contamination around many homes. They operated until 1992.

A greater sense of isolation for Black Austinites from the mainstream of commerce and city and state government occurred when construction began in the 1950s on an interstate highway that would run through the center of the city, separating east from west. What was once an open and accessible boulevard – East Avenue – eventually would be consumed by a 6-lane freeway with additional traffic lanes added later to a deck built above the freeway.

For some who lived on the eastside, Interstate 35 would create a concrete barrier between the prosperous and predominately white downtown and West Austin and their neighborhood on the “other side of town.”

But there were positive changes, too. During the 1950s, there was growing awareness on the part of politicians and the courts that Black Americans deserved the same opportunities as whites. With the passage of Civil Rights legislation and the Voting Rights Act of the 1960s, Black participation in political life took on new urgency.

The first Black American elected to public office in Austin occurred in 1968 when Wilhelmina Delco won a spot on the city’s school board. In 1974, she was elected to represent Austin in the Texas Legislature until she retired in 1995. In 1971, Austin elected its first Black city council member, Berl Handcox.

Voter registration projects became a centerpiece of East Austin political life in the 1980s and 1990s as did political activism by the local chapters of the NAACP, Urban League and the Black Citizens’ Task Force among others.

Families in East Austin won a victory in the courts in 1996 when oil companies agreed to dismantle the petroleum storage tanks near their homes.

Still, change was in the air for East Austin as gentrification took root over the past decade, leading many to believe that rising home values forced many long-time residents to leave. While that’s partially true, historian Lisa Byrd has written that even in the 1970s, before the gentrification that forced many long-time families to move away, Black families had begun moving to the suburbs and smaller communities surrounding Austin, some to be near schools where their children were being bused daily under the school board’s desegregation efforts.

For Black Americans in Austin, past and present, it's been a long history of struggles and triumphs, with so many new chapters of that history yet to be written.