Texans share their experiences with mental health during the pandemic

KVUE spoke to families, families of long-term care facility residents, health care workers, people experiencing homelessness and more about their mental health.

Resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, there are resources available.

Resources for children:

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychology's (AACAP) resources for helping kids and parents cope amidst COVID-19

- CDC: Children's Mental Health

- National Alliance on Mental Illness' Lighthouse

Resources for older adults:

Resources for health care workers:

- American Medical Association: Managing mental health during COVID-19

- American Psychological Association: COVID-19 information and resources

- CDC: How to cope with stress and build resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Mount Sinai Center for Stress, Resilience and Personal Growth

- NAMI: Health care professionals

- Physician Support Line (1-888-409-0141)

Resources for people experiencing homelessness

Resources for young adults

- Austin Community College Counseling Center online appointment scheduler

- CDC: Support for teens and young adults

- OutYouth Austin (512-419-1233)

- St. Edward’s Health and Counseling Center (512-448-8538)

- UT Counseling and Mental Health Center (512-471-3515)

Resources for all:

- Crisis Text Line (text TX to 741741)

- Integral Care's 24/7 Crisis Helpline (512-472-4357), Psychiatric Emergency Services, Mobile Crisis Outreach Team and Mental Health Urgent Care

- Integral Care Mental Health Toolkit

- NAMI's list of warning signs and symptoms

- NAMI of Central Texas

- NAMI's COVID-19 Resource and Information Guide

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255)

- PsychHub

- The SIMS Foundation

- Texas Health and Human Services COVID-19 Mental Health Support Line (1-833-986-1919) and other COVID-19 behavioral health resources

- The Trevor Project

- Veterans Crisis Line

If you break a bone, you go to a doctor. It’s not something to be ashamed about. It’s something that needs help to heal.

So, why is there so much silence around anxiety, depression and other mental health struggles? Isn’t mental health just as important as physical health?

We want to remove the stigma surrounding mental health by talking about it.

The pandemic has impacted each of us in some way. COVID-19 has taken a toll physically, mentally and emotionally. Throughout the next few chapters, we’ll be talking about mental health and how the pandemic has impacted the way we feel and think. We'll also be taking a look at data and medical studies to demonstrate that no one is alone in dealing with mental health.

Every day this week, a new chapter will be added to this story. The chapters will focus on kids and families, families of residents in long-term care facilities, health care workers, people experiencing homelessness and young adults.

The effects of the enduring pandemic are weighing on all of us. Let's talk about it.

Families

Meet Any Canizales. She’s a mom of three, a wife and an ER nurse.

"It has been the most interesting first year of nursing, I think, that I could have imagined," Canizales said. "I actually started working on my unit two weeks before COVID was a thing and shut us completely down."

Over the past year, Canizales also picked up a job at a rehabilitation center and, like many other parents during the pandemic, she added teacher to her resume as her kids shifted into virtual learning for part of the year.

"I think that's where I've struggled the most this year because I've questioned a lot on how I'm parenting and whether I'm meeting my expectations for them and their emotional needs and are they getting their homework done? And it's just been a lot with coming home after 12-hour shifts in a world that was completely new to me. And then now, all of a sudden, being a teacher, which I've known all my life, I'm not meant to be a teacher,” Canizales said, laughing a bit.

When you’re raising a 10-year-old, eight-year-old and five-year-old, much like the kids themselves, life doesn’t seem to slow down. But that changed with the pandemic.

Canizales said when her kids' school moved virtual, her oldest, a fourth-grader diagnosed with ADHD, saw his grades drop.

"While he's always been distracted, it's never been as bad as this year was," she said.

Her son was not alone.

"It's been a national problem that kids are not doing well. Like the grades are going down and schools have had to make adjustments in terms of the requirements, which is really sad," said Dr. Joanne Sotelo, a psychiatrist at Baylor Scott & White Health.

Sotelo said she’s had more referrals overall than ever.

"It’s very different," she said. "It's not your typical referral for attention problems or [a] little misbehavior here and there."

Sotelo said poor mental health has been a pandemic of its own. And data backs her up.

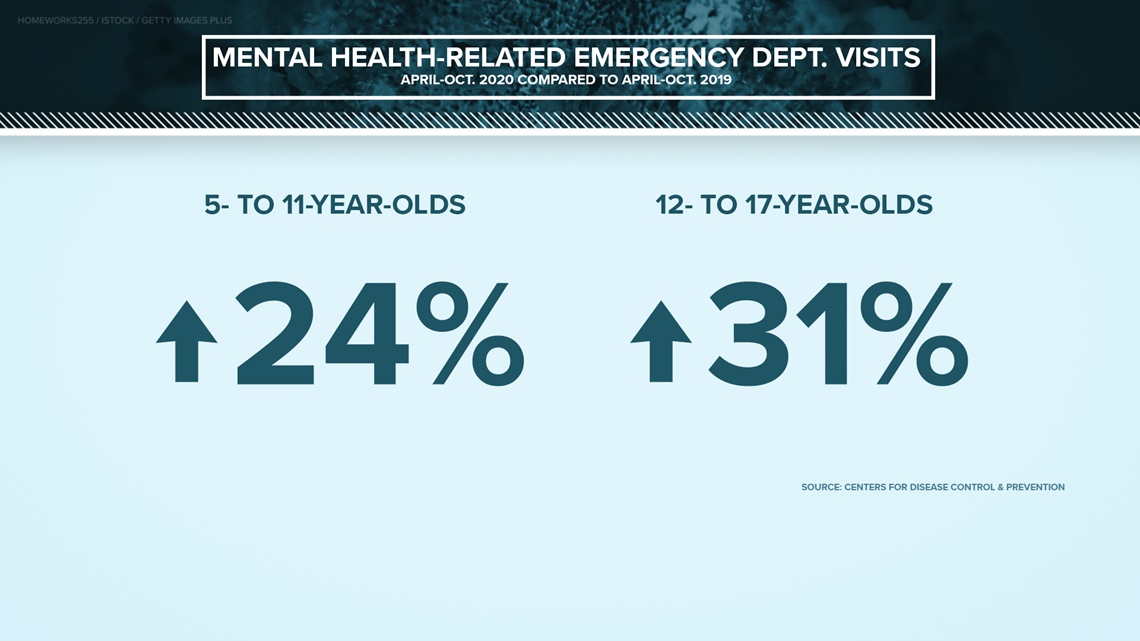

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that between April and October of 2020, children's mental health-related emergency department visits in the U.S. not only increased but remained high. Compared to the year before, visits for kids ages five to 11 increased by 24%, while visits for 12 to 17-year-olds increased by 31%.

"The kids are struggling a lot also with sadness and anxiety and kind of disconnection socially," Sotelo added.

Canizales experienced those struggles with her family, as well.

"Having to explain to them, especially in the beginning of the pandemic, 'No, you can't go next door tonight or you can't go across the street to your friend's house today,' and then today turn into a week and a week turned into, you know, we're 12 months into this thing," Canizales said.

Even though she joked about her frustrations with math changing since she was a kid, Canizales said trying to get her children to understand the social impacts of a global pandemic was one of the toughest lessons she had to teach them.

"Because you can't really teach them the seriousness of what's going on in a way that they fully understand. So, there was a lot of crying. There was a lot of, 'Why? Is she not my friend anymore? Do they not like me anymore?'" she said.

"They like to be social, even as infants. I had them everywhere at parks, had playdates. I never wanted them to be scared of certain people or animals or [any] environment. So they've always been social butterflies," Canizales continued, tearing up. "And to kind of stop that cold turkey was, was very rough."

RELATED: Kindness Campaign uses murals to raise money for emotional and mental health tools for kids

She said her kids went months without seeing their friends.

“It took a long time and a lot of tears and a lot of kind of counseling to make them understand that it was it was nothing that they had done. It was just the way things were at the moment," Canizales said.

As her kids questioned where their friends were, Canizales started questioning herself.

"Where am I going to go wrong as a mother? Where am I going to go wrong as a nurse? Where am I going to go wrong as a wife? Because it's been an unprecedented level of stress, not just for me, but for every mother and every parent out there," she said.

She said she is back on anxiety medication, which has helped her cope and to stay focused on her family.

Sotelo offered some tips for parents whose kids may be struggling with their mental health or just the changes brought on by the pandemic.

"Mental health is difficult to understand, even for adults. We have our own ideas about it, our own stigma. So, that would be probably the most important thing to start is awareness. Awareness of not just how the kids are doing in terms of their work, but then also emotionally," Sotelo said. "Then awareness of where are we, how are we doing, and what do we believe in in terms of mental health. And do we have [a] stigma?"

She said conversation is the first step, followed by acting how you want your kids to act – talk about your emotions and how you’re feeling. But how to talk to children varies with age:

- For young kids: "It is important to recognize that even if they are very smart in terms of brain development, they do not have the capacity for abstract thinking. They are very concrete, very black and white. So, we have to talk to them in terms of what they can understand and see. But we can talk about feelings, and we can talk about behaviors. Most kids, even very young, they can say, 'I'm sad, I am mad.' They might not say anxious, but they'll show that with repetitive play and things like that. They are worried and it's OK."

- For middle school-aged kids: "They already have done abstract thinking capacity, and they know a lot, so we can talk to them more directly. We can use the words depression, anxiety, ADHD, even the word suicide because they are hearing about it. They are reading about it … So we have to pay attention to them and acknowledge it and talk to them about it. They have a lot of questions, and we need to answer them. Honestly, you don't have to give them all the details, but we do need to be honest and straightforward."

- For teens: "Even though their brains are almost adult level, they are not going to want to talk to us as much. They'll be talking to their friends more, but then they might have more misinformation about it. So, we have to be able to have that open conversation here and there with them and give them space and let them know that we are here and that they can come talk to us for whatever they need."

Sotelo also said parents need to remember to take care of themselves.

"We have to be fine, and fine is, doesn't mean 'I am perfectly calm and happy.' No, it's feeling what we have to feel and still move forward, take care of ourselves, sleep well, eat well, exercise, do a little bit of mindset work and role model that for our kids. The best gift that we can give to our kids is having a very loving, open environment where they feel like they can come to us in a trusting way, and that's a gift that they'll have forever," Sotelo said.

For more mental health resources for children, head to the last chapter.

Families of long-term care facility residents

Meet Veronica Alcala. She had to make the tough decision to move her mother into a long-term care facility after she was diagnosed with mild dementia.

"My mom was a very, very independent woman, strong persona. Her dementia wasn't too bad. She always remembered me. She was forgetful with names at times, but she knew what she wanted and when she wanted it," Alcala said, laughing. "I would visit her every day. My mother and I were very close."

Those daily visits changed when the pandemic hit.

"I remember leaving the last day and telling her … 'I'll be back tomorrow to do your hair.' Because I’d always dye her hair or comb it and curl it," Alcala said. "She used to be a hairstylist, so that's something she'd always had to have on point."

Long-term care facilities across the country started shutting down, and the place where Alcala’s mom stayed was no different. Alcala was limited to visits through a window.

"At first, it was just soul-crushing because I was unable to make any decisions about her care and I was unable to do the things that I was doing every day," she said.

Mary Nichols understands Alcala’s frustration more than most. Her mom is also at a long-term care facility, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

That’s just one reason Nichols started Texas Caregivers for Compromise in July.

"It took me several weeks to get frustrated enough to begin the petition and start looking for other people like me. But it didn't take very long for me to find those people," Nichols said.

By August 2020, she said her petition had thousands of signatures. Texas Caregivers for Compromise then introduced a proposal for an essential caregiver program to Texas Health and Human Services.

In September, Gov. Greg Abbott announced nursing home facilities in the state could open back up for essential caregiver visits.

"I really believe that this mental health crisis is on both sides of the facility walls. Families have endured such an excruciating level of pain and anxiety and uncertainty," Nichols said.

Both families and facility residents have been impacted.

"I've had patients who describe their experience in assisted living as being in a minimum-security prison," said Dr. David Murdy, a geriatrician with Baylor Scott & White Health.

He said families often have to make the tough decision of moving a loved one into a long-term care facility.

"Their family members want them to stay safe. But it is often the daughter, the husband, the spouse who can best interpret, reassure them, provide support to them," Murdy said.

Feelings of isolation are just one of the pandemic’s impacts on people’s mental health.

"I think it's the hardest thing. It does play a big role with your mental health. The decline, I think it's the biggest – it's the worst. I believe they felt lonely. They felt forgotten," Alcala said.

The hope for any kind of contact became even bleaker when there was a COVID-19 outbreak at Alcala’s mom’s facility over the summer. She said her mom tested positive.

"It was downhill from there. She can no longer use the phone, she can no longer call me, she could no longer speak when I spoke to her or when I would video chat, she was always asleep," Alcala said.

Alcala went about six months without being by her mom’s side – 210 days before the governor ordered that visits could resume on Sept. 24.

She was back in her mother’s room the first day.

"To my surprise, my mom could no longer communicate. My mother could no longer move," Alcala said. "It wasn't her anymore."

The next morning, she learned her mother had died.

"It’s very hard to deal with, especially when you've been attached to a family member or your parent for so long and, in that way, I miss her every day," Alcala said. "There's not a point in time that I don't think about her. It's very hard. The anxiety, the mental anguish. What could I have done? Was this my fault? It's just – it's heartbreaking."

Even through loss, Alcala said her family has been a lifesaver.

"They’ve taught me that you have to cherish every moment that you have, and I am so glad that I was able to be there when I was for my mother," Alcala said. "That's something that nobody could take away from me."

Murdy said isolation definitely can impact health, especially at an older age.

"It can be devastating. It's not uncommon to see people decline faster under these kinds of conditions than they might have if they had had more or frequent contact with loved ones," Murdy said.

He encouraged people to find interaction where they can.

"We have to overcome the health effects, the negative health effects of some of our lockdowns with other strategies that can improve people's communication, interaction with their families. Technology can be a great aid for that," Murdy said.

For mental health resources, head to the last chapter.

Health care workers

Meet Aly Quiambao, Dr. Nick Steinour, Dr. Karen Smith and Tami Taylor.

Quiambao is a medical ICU registered nurse at Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Steinour is the emergency department medical director at Ascension Seton Medical Center. Smith is a senior staff physician at Baylor Scott & White Health. And Taylor is the chief nursing officer at St. David’s Round Rock Medical Center.

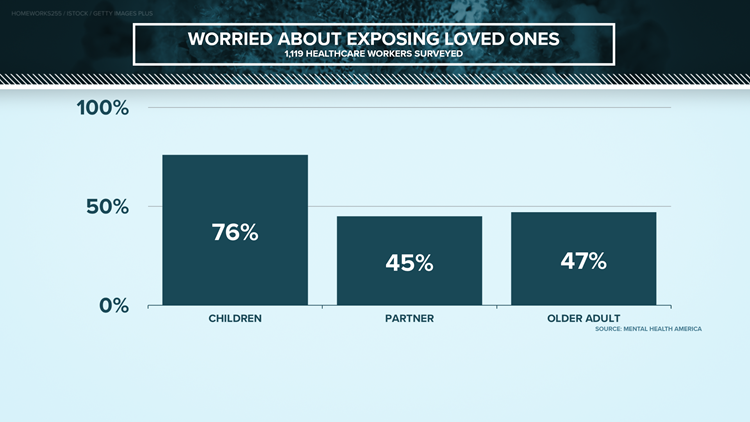

Each of them has families, loved ones that they care about. And each has dealt with the harsh reality that doing their jobs could bring COVID-19 back to their families.

"There was concern. There was concern about, 'Are we going to survive this? Are we going to get sick? Are we going to take this home and get our loved ones sick?'" Steinour said.

Smith echoed his concerns.

"How do you make sure that you're keeping them safe while putting it all on the line for your patients?" he said.

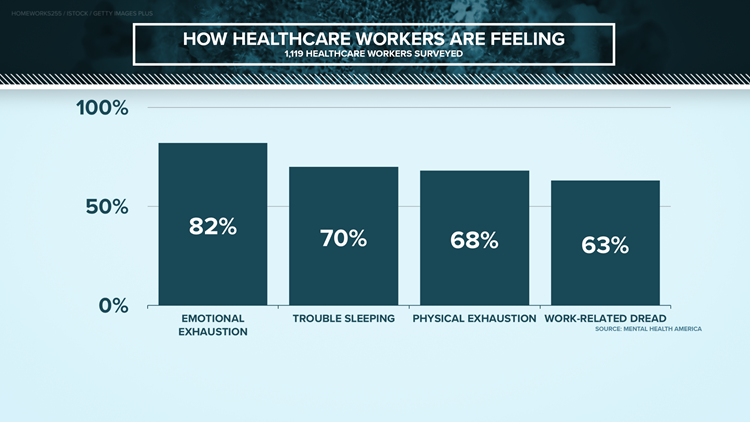

Along with worries of catching COVID-19 and passing it on to someone else, the pandemic brought burnout.

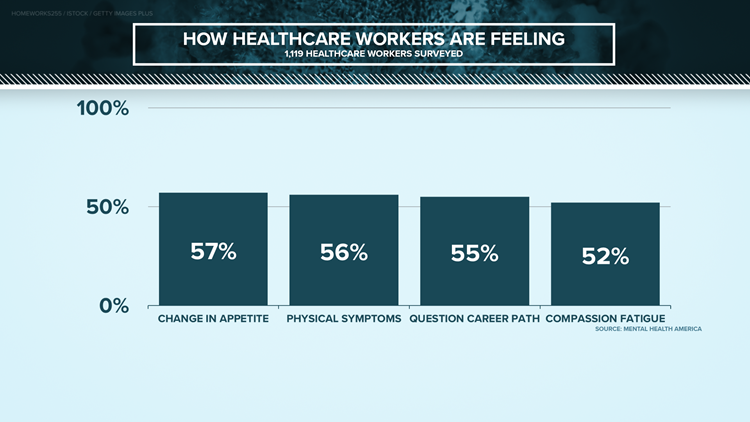

"There was a lot of crying moments. There was, in the beginning, there was a lot of fear," said Quiambao, who added that she even started questioning her career choice.

She said some days she just felt like a failure.

"Our exterior is like, ‘Oh, I'm an ICU nurse. Yes, I can do this. I take care of the sickest patients.' Like, that's the exterior. However, in the interior … there are times where I have felt like, ‘Wow, I've given my 100,000%. However, I feel like I still failed.’ It's like, yes, I'm taking care of them, but also why do I feel like a failure? Because I just sent them off down to the morgue. That was like, one of the hardest things, I think, to come to reality," Quiambao said.

Quiambao and the others aren’t alone.

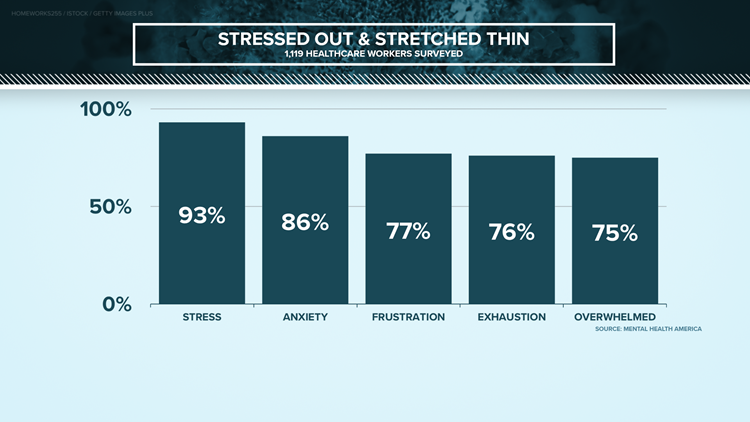

Mental Health America reports 93% of the health care workers it surveyed are stressed out, with more than 75% saying they’re frustrated and burnt out – showing no one is immune to the pandemic taking a toll on their mental health.

GRAPHS: How health care workers are feeling

Anne Marie Warren is the research center director for behavioral health for the Baylor Scott & White Research Institute. She is working on a long-term study regarding the impacts of COVID-19 on essential workers.

While the results aren’t in for that study, she said burnout is a common theme among health care workers.

"In addition to looking at the negative psychological symptoms that people may be having, we're looking at things like resilience and coping in health care workers from this study and from other studies that I've been involved with that we've done. Health care workers tend to be highly resilient," Warren said.

But like many of us, health care workers have faced personal loss.

"My brother passed away in April," Smith said. "I just went home and sat down and stared at the wall and took some bereavement days off, and that was all I could do."

Quiambao said days working in the ICU, witnessing people dying, took a major toll on her mental health.

"I just curled up in a fetal position. I was just crying," she said, recalling one of the toughest days when she didn’t even want to go to work. "I think I broke down there just because of the toll that it has taken. Because every day at work, that's all I see, that's all I had to experience."

Through all the struggles, health care workers kept showing up.

Especially at the beginning, there was a lot of love from the community. However, health care workers said they learned leaning on each other helped more than they would’ve thought.

"I've had many conversations that I've never had pre-pandemic – and I've been doing this long enough that most conversations and topics have been broached, most you wouldn't want at a dinner party," Steinour said, laughing. "But it's really brought to light the importance and the need to recognize your own vulnerabilities and address them and recognize you're not alone in this."

Here’s what helps the four health care workers KVUE spoke to:

Quiambao: "My mom works is a nurse as well, at the same hospital, just in a different floor, and her partner as well. So, I just vent and I just unload on them because I know that they will understand where I'm coming from. So that helped a lot … I'm not a crier. It'll take me a while to even break down. So, I think allowing myself to feel those emotions and allowing myself to be true to my emotions have helped me. And then, of course, dogs. I mean, our pets – get a pet, but make sure you take care of them. But they've helped a lot as far as if I'm – just before work or when I wake up, it would just be immediate kisses and nose boops and all that, so that has helped me, has helped my mental health. Honestly, I mean, yeah, they don't understand what you're talking about, but just being able to hug and snuggle somebody or something. My dog has helped me go through with all of this emotional rollercoaster of life."

Steinour: "I found myself outdoors much more. I think being able to get outside, even if it's for just a short walk, get some sunshine on your face, be able to take your mask off. I found that rejuvenating. I've found myself listening to things like Headspace, where there's sort of intentional meditation and mindfulness to center my thoughts so that you don't kind of get in this circular pattern of worry causing anxiety, causing more worry, causing more anxiety. So just the ability to kind of have intention around thought and kind of quiet the mind, that's something that I hadn't really explored before. But certainly, during this, I found to be helpful. Communicating with friends – I do a lot more intentional calls, especially with those friends that I've previously had close relationships with and now distance or profession has kind of driven us apart a bit. Reconnecting with them and kind of centering and finding that grounding has been helpful to kind of understand where I'm at, where I'm going. And then there are resources out there like counseling. The county medical society has some free services available. And then our hospital, as well as our organization, has some counseling lines where you can call and talk to somebody."

Smith: "Take small steps like, 'OK, well, I don't know much, but I know I can wear a mask and sit six feet away from the patient and wash my hands for 20 seconds.' And that's an anti-anxiety action because now I'm in control of doing that thing … I learned the things I could do. And then you kind of have to reframe. I had to come to the point of what if my loved one got COVID and see the worst happening and see myself surviving that. And that's a technique for managing anxiety. It's not an easy one and not everyone's always ready for it. But imagine the worst happening and see yourself surviving. And then my faith – and for me, that was huge, huge, huge. You have your belief system that you fall back on."

Taylor: "Instead of coming to work and then going to work out and doing other things outside of work ... We all work long hours and then I go home. So there really isn't a lot in between. And you have to fill in that those gaps and really try to help yourself with your mental health by doing things like cooking and music and other ways to have an outlet other than what we used to do. Something that's been a great distraction for me is I'm in school right now getting my doctorate. And so, that has been something that whenever I go home that I can focus on."

For more resources for health care workers, head to the last chapter.

People experiencing homelessness

Meet Amie Parker. She became homeless after moving to Austin in 2019.

She now lives under Interstate 35.

“We have maybe about 10 to 11 people here, so quite a large family you might say,” Parker said.

She said two more women may soon be coming to the camp to get away from “bad situations.” That’s just one reason Parker calls the camp “Camp Safe Haven.”

“Come be safe. Warm yourself by the fire. Talk to anyone that is around and that's what makes me feel good,” she said.

Parker said she tries to stay pretty positive. But living an already isolated life in the middle of a pandemic can have some negative impacts on a person’s mental health.

“It's really taken a toll. I've gone downhill. I've been uphill, I've been downhill, it's been a rollercoaster for me,” she said.

Mark Hilbelink, the director of Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center, said mental health assistance is difficult to access for most people. He also said therapy is pretty much nonexistent for the homeless community, leaving many with solely medicinal options.

“But then they don't take it correctly or they don't know how to take it correctly or they get it stolen or they lose it. And just – the odds of someone actually making it from the point where the doctor writes the script to the end of the script is virtually impossible,” Hilbelink said.

To add to the obstacles, Hilbelink said people don’t always have access to reliable transportation to make it to appointments or access to a phone for services like TeleMed.

“And TeleMed is reliant on you having the same piece of technology that you had three weeks ago when you did your last appointment. And for most people experiencing homelessness, the odds of them having the same piece of technology they had three weeks ago, whether it's a phone or a tablet or computer, is very, very low,” Hilbelink said. “And to compound that, a lot of the agencies that helped the homeless and allowed them to gain access to the Internet or gain access to technology in their spaces, including public libraries and many of the social service providers, closed down during the pandemic.”

Both Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center and Integral Care’s PATH (Programs for Assistance in the Transition from Homelessness) team have continued serving people throughout the pandemic.

“The process hasn't changed,” said David Gomez, a program manager for Integral Care’s PATH Team. “We're doing the same thing we were doing before COVID. The number of people we're finding is greater at the campsites.”

The PATH Team goes into camps, looking for and getting resources to people who are experiencing homelessness and struggling with mental health or substance abuse.

“Even when they have a sense of community, they still feel isolated by the major community,” Gomez said, adding that each person who is homeless has faced their own kind of storm.

Both the PATH Team and Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center are working to fight that feeling of isolation.

Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center is pretty much a one-stop-shop when it comes to homeless needs. Folks there say one of their favorite parts about Sunrise is it just give people a place to gather.

As for the PATH Team, Parker said she feels safer knowing people are coming to check on them.

“My mental health has gone from like, say, on a scale of one to 10 – one being the worst, 10 being the best – it's gone from a two, of being or feeling separated, isolated, to now being maybe eight on the scale. We're almost there to a 10, but we could always use more.”

There’s still work to be done to help those who are homeless deal with their mental health.

“Almost every person experiencing homelessness has endured some sort of trauma and some would argue are experiencing trauma every single day,” Hilbelink said. “To not have access to any sort of counselor or any sort of therapy options in addition to the medication is really kind of like short-handing the response right from the start.”

For resources, head to the last chapter.

Young adults

Meet Alexandrea Tagle. She graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in May 2020 with a Bachelor of Science and Psychology. Now, she’s applying to graduate school for nursing.

Like many 2020 graduates, Tagle’s final spring semester quickly changed once the pandemic hit.

“The pandemic started right before spring break. That turned into two weeks. That turned into not going back to campus. That turned into, ‘Oh, you can't come in for volunteering,’” Tagle said. “We had to pause everything, [start] social distancing. And I think the hardest adjustment was, we were navigating this new step in life, excited for graduation, and then it wasn't what you're taught it would be.”

She said everything she worked for suddenly felt far from reach, taking a toll on her mental health.

“There were days that it just felt endless, like this was never going to end. Like we were always going to be stuck inside and just trying to navigate this by ourselves,” Tagle said. “So I did feel like there was some days that were really down, and it was hard to get out towards the end of that and to keep things in perspective, especially with COVID being so unknown in the future. It's even harder to grasp that."

Over the past year, young adults across the country had graduations, both high school and college, move virtual. They had potential employers implement hiring freezes. Some internships were put on hold. Many also lived in cities that had protests over the summer and they experienced their first presidential election.

“We still are in disbelief that we've been through all of this in the short amount of time that it was,” Tagle said. “It feels like the last year of the pandemic has been an eternity. It feels like it's been years. I feel like our time went from feeling like it was going really fast to feeling like it was lasting forever.”

Tagle said she often felt like she was no longer in control of her life and sometimes even felt like a failure.

“It was hard to get out of bed. It was hard to make your goals for yourself when you're not seeing those things in person moving forward,” she said. “And I did find it really difficult.”

Tagle isn’t alone. Dr. Kim Kjome, a psychiatrist at Ascension Seton Shoal Creek, said young adults are balancing a lot of stress-inducing situations on top of a year filled with unknowns and isolation.

“Oftentimes, they've been told up until this point … they’re in control of their own destiny, their grades they make or what kind of determines what happens next. And this is something that they have no control over,” Kjome said.

She said young adults can be a vulnerable community, and the implications of the pandemic can make them even more susceptible to mental health challenges.

“We've had a lot of people come into the hospital in crisis during this time,” Kjome said, adding that this crisis will “define this generation.”

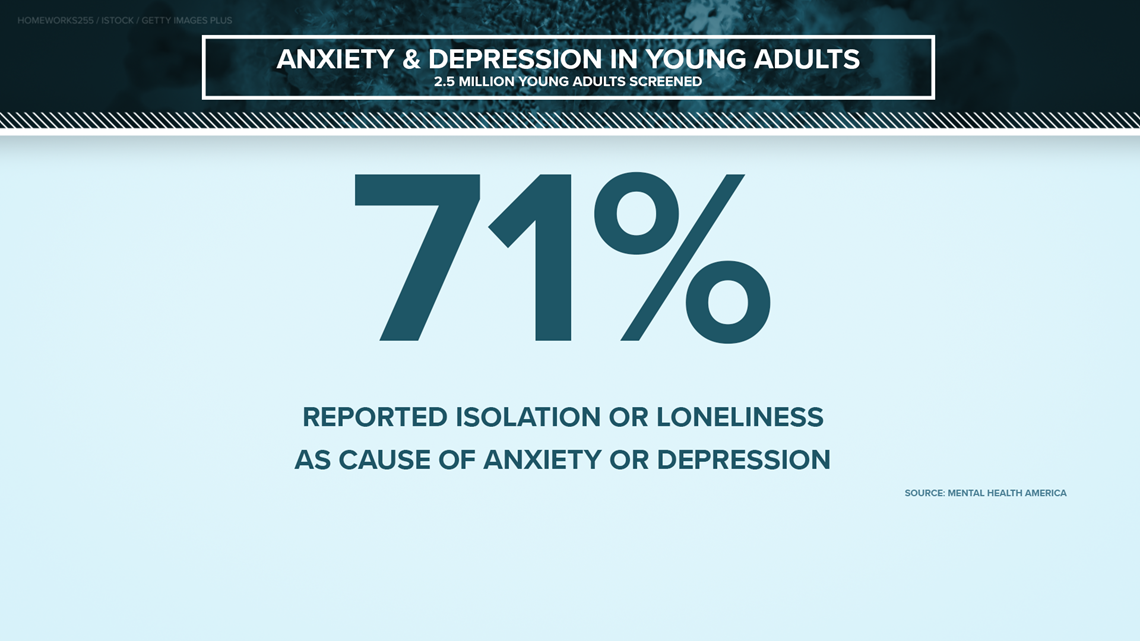

Between April and December of last year, Mental Health America screened 2.5 million people. Of those, 71% reported isolation or loneliness was the reason for their anxiety or depression.

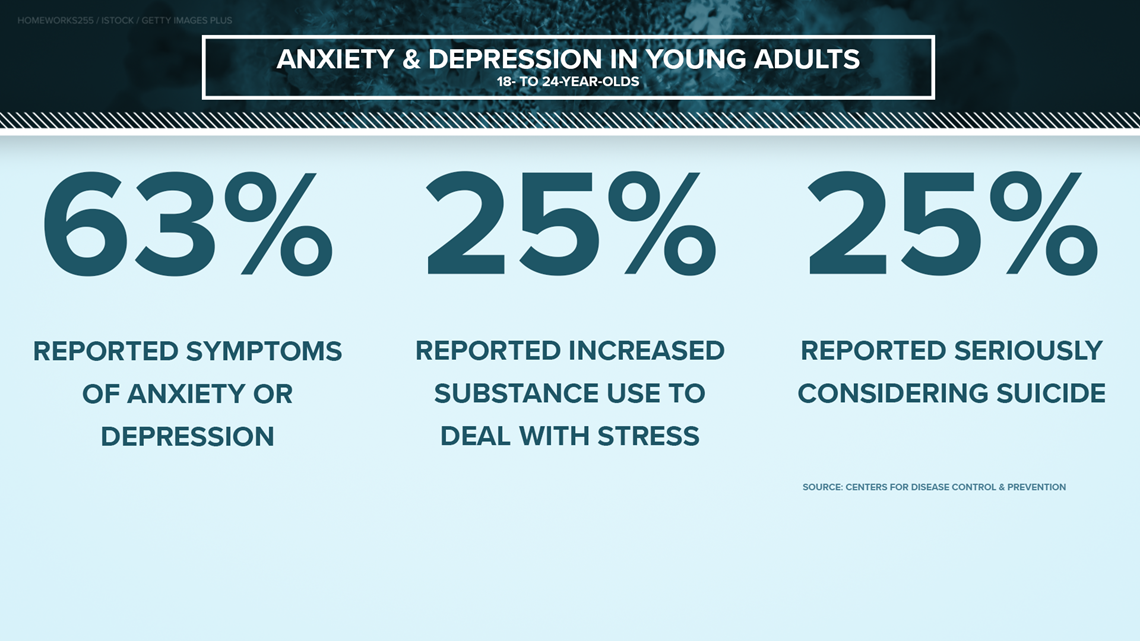

The CDC surveyed young adults and found 63% reported anxiety or depression symptoms. A quarter of those surveyed also said they had seriously considered suicide.

“These are foundational years that we have always looked forward to and these [are] foundational years that start your career. And when they don't work out as planned, it can be really devastating. And when things aren't going as quickly as you would like, it feels like a setback. And I think people should be more understanding of that,” Tagle said.

Tagle said she decided to go to therapy and get medication for anxiety and depression. She said it’s helped her see “more of a light now.” As she looks for the silver lining, she said the pandemic has given her hope in herself.

“It has kind of given us skills to handle this stress and to navigate new things and to not be afraid of the unknown. And I think that was the hardest part of dealing with it,” Tagle said. “But I'm glad I've gone through it now, although it's been really hard. I wouldn't change anything, what I did and what I have done, because I feel like I've gotten very strong after all of this.”

She said, along with therapy, talking with her peers has helped a lot. It has helped them all understand that they aren’t alone in feeling defeated or isolated.

For more resources for young adults, head to the last chapter.

Resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, there are resources available. This section will be updated daily.

Resources for children:

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychology's (AACAP) resources for helping kids and parents cope amidst COVID-19

- CDC: Children's Mental Health

- National Alliance on Mental Illness' Lighthouse

Resources for older adults:

Resources for health care workers:

- American Medical Association: Managing mental health during COVID-19

- American Psychological Association: COVID-19 information and resources

- CDC: How to cope with stress and build resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Mount Sinai Center for Stress, Resilience and Personal Growth

- NAMI: Health care professionals

- Physician Support Line (1-888-409-0141)

Resources for people experiencing homelessness

Resources for young adults

- Austin Community College Counseling Center online appointment scheduler

- CDC: Support for teens and young adults

- OutYouth Austin (512-419-1233)

- St. Edward’s Health and Counseling Center (512-448-8538)

- UT Counseling and Mental Health Center (512-471-3515)

Resources for all:

- Crisis Text Line (text TX to 741741)

- Integral Care's 24/7 Crisis Helpline (512-472-4357), Psychiatric Emergency Services, Mobile Crisis Outreach Team and Mental Health Urgent Care

- Integral Care Mental Health Toolkit

- NAMI's list of warning signs and symptoms

- NAMI of Central Texas

- NAMI's COVID-19 Resource and Information Guide

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255)

- PsychHub

- The SIMS Foundation

- Texas Health and Human Services COVID-19 Mental Health Support Line (1-833-986-1919) and other COVID-19 behavioral health resources

- The Trevor Project

- Veterans Crisis Line

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: