Cinnamon is a staple in many kitchens, whether sprinkled on oatmeal and coffee or used as an ingredient in everything from snickerdoodles to five-spice chicken. Some people even take large daily doses of the spice for its purported health benefits.

So it was alarming when an outbreak last fall of lead poisoning among more than 500 children was traced back to the cinnamon in three brands of apple purée pouches. A few months later, the Food and Drug Administration warned consumers to avoid 17 ground cinnamon products because they contained lead levels that, while much lower than what was in the apple purées, were high enough to pose a health threat when consumed regularly.

That news prompted CR to ask: What’s going on, exactly, and how worried should consumers be about cinnamon?

To find out, our food safety scientists tested for lead in 36 ground cinnamon products and spice blends that contain cinnamon, such as garam masala and five-spice powder. We purchased products from brands like Badia, McCormick, and Morton & Bassett that are carried in mainstream grocery stores, as well as smaller brands available in stores that cater to international cuisines. The spices were purchased from 17 stores in Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and online. (Read more about how we tested these spices.)

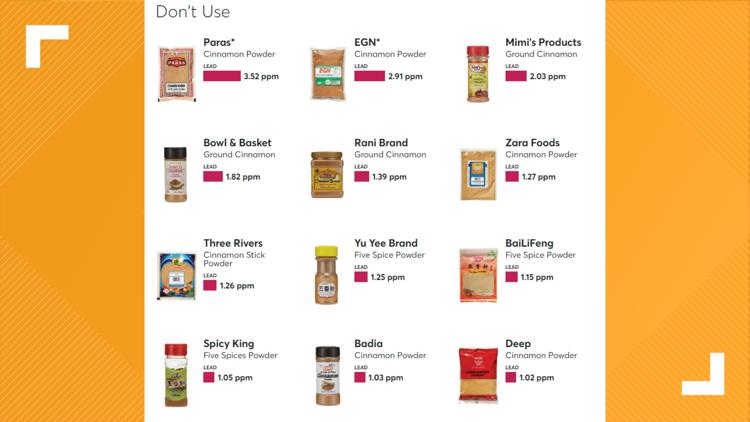

The findings were troubling: 12 of the 36 products measured above 1 part per million of lead—the threshold that triggers a recall in New York, the only state in the U.S. that regulates heavy metals in spices. While CR does not do compliance testing, the results raised concerns for our experts, and we shared our data with New York officials so that they could investigate further.

Just a quarter teaspoon of any of those products has more lead than you should consume in an entire day, says James Rogers, PhD, the director of food safety research and testing at CR. “If you have one of those products, we think you should throw it away,” he says.

“Even small amounts of lead pose a risk because, over time, it can accumulate in the body and remain there for years, seriously harming health,” Rogers says.

Exposure to lead is of greatest concern in children and during pregnancy because it can damage the brain and nervous system, causing developmental delays, learning and behavior problems, and more. However, adults can also experience negative effects. For example, frequent lead exposure has been linked to immune system suppression, reproductive issues, kidney damage, and hypertension.

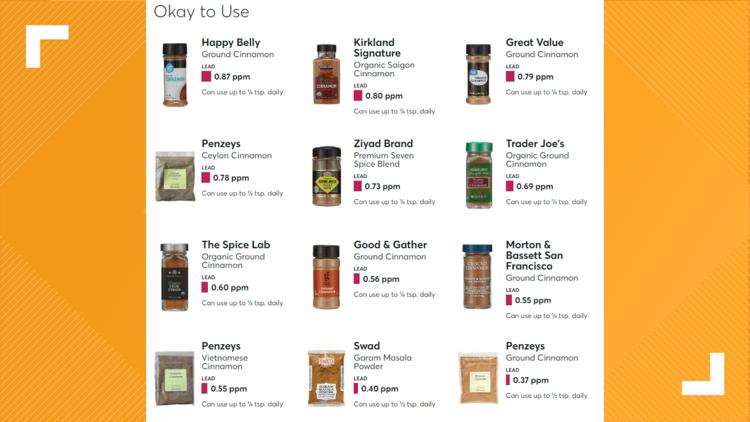

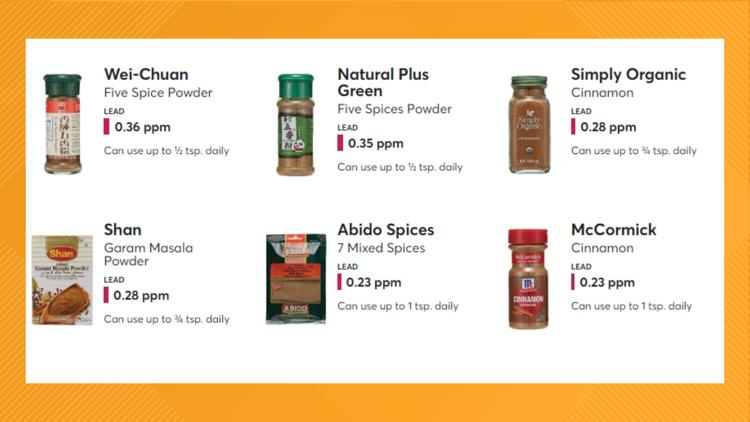

CR did find several cinnamon products that are good options for consumers. The six posing the lowest risk in our tests are 365 Whole Foods Market Ground Cinnamon, 365 Whole Foods Market Organic Ground Cinnamon, Loisa Organic Cinnamon, Morton & Bassett San Francisco Organic Ground Cinnamon, Sadaf Cinnamon Powder, and Sadaf Seven Spice blend.

“These products demonstrate that it’s possible to produce cinnamon with no lead or extremely low levels,” Rogers says.

Finding lower-risk alternatives is consistent with CR’s 2021 original spices investigation, which examined more than a dozen types of spices, from basil to turmeric (but did not include cinnamon).

PHOTOS: The 12 cinnamon powders you should never use

CR’s Tests Prompt Manufacturers to Take Action

After being informed of our results, the two companies with the highest lead levels—Paras and EGN—told CR that they would stop selling their products and that they had told stores to remove the products from their shelves. Mimi’s Products, with the third-highest cinnamon powder, did not respond.

Of the nine other companies with products above 1 ppm, only two replied: Deep and Yu Yee. Both said that they tested their product or relied on tests from their suppliers.

We also asked companies with lower lead levels what they do to limit the heavy metal in their products. We didn’t hear back from any of those with the least lead but did hear from three other companies with relatively low levels.

McCormick told us it monitors “environmental conditions that may increase the natural occurrence of heavy metals.” Penzeys said it grinds its own spices and “the raw material is tested prior to grinding.” And Simply Organic said that it has adopted New York state’s limits and that it conducts “comprehensive in-house inspections and additional product testing for every shipment of incoming material.” (CR’s food safety experts say that while those measures are good, it would be even better to test the finished product.)

How Lead Contaminates Cinnamon

Cinnamon comes from the inner bark of trees that belong to the genus Cinnamomum.

Heavy metals, such as lead, are naturally occurring elements in the Earth’s crust, says Laura Shumow, executive director of the American Spice Trade Association, an industry group representing spice companies responsible for more than 90 percent of the U.S. market. “Any natural product that comes into contact with soil or groundwater has the potential to take up trace amounts of lead that cannot be removed.”

Soil can also be contaminated with lead from industrial byproducts. According to Shumow, the 10 or so years cinnamon trees need to grow before the bark can be harvested makes the spice particularly prone to lead contamination simply because the plant has a long time to absorb any lead present in the soil. And, she says, whatever lead is in the bark can become concentrated in the finished product during the drying process.

What’s more, nearly all cinnamon sold in the U.S. is imported, with most of it coming from Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. Francisco Diez-Gonzalez, PhD, director of the Center for Food Safety at the University of Georgia, says those countries may have fewer regulations or enforcement regarding chemical contaminants—pesticides or industrial byproducts, for example—found in soil.

Lead could also enter cinnamon from processing equipment, storage containers, or packaging, says CR’s Rogers.

Perhaps the most concerning thing for consumers, Shumow says, is that there’s no way to remove lead from the cinnamon (or any herb, spice, or food for that matter) once it is present, or to prevent the trees from absorbing lead from the soil in which it is grown.

She says the industry is currently conducting research on how and why trees that produce cinnamon absorb lead from the environment and what could be done to mitigate it, but it could take years before they have an answer.

Inconsistent Regulation

There are currently no federal limits for lead in cinnamon or other spices. But Enrico Dinges, a spokesperson for the FDA, says that even without a limit, the agency can take action against a product, such as issuing a health alert, if it learns the product has excessive levels either from the agency’s or a state’s testing.

The FDA didn’t answer CR’s question about what level of lead would trigger such an alert or recall, saying instead the agency issues them on a “case by case basis." The FDA used that authority when it recently warned consumers to avoid 17 ground cinnamon products. All of those products had lead levels above 2 ppm, which is comparable with a limit recently proposed by the European Union for how much lead is allowed in herbs and spices.

Earlier this year, while discussing the agency’s health alerts issued for ground cinnamon with high lead, Conrad Choiniere, PhD, acting deputy director for regulatory affairs within FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said, “Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the manufacturers and the importers to ensure the safety of the products entering the U.S. market.”

The FDA told CR that it could not comment on our test results but added that it regularly reviews ground cinnamon test results from states.

By contrast, New York state set a 1 ppm limit for lead in spices in 2016. Any spice over that limit is subject to recall by the state. In fact, New York state has since recalled more than 100 spices due to heavy metal contamination.

When CR informed New York state’s Department of Agriculture that 12 products we tested had lead levels above 1 ppm, the agency said it could not comment on our test results but that it regularly monitors food products, including spices, for hazards and "takes swift action to remove these products from shelves" when problems are found.

Brian Ronholm, director of food safety policy at CR, says the federal government should follow New York in setting a national policy on the amount of lead allowed in herbs and spices, including cinnamon, and other foods.

“Ultimately, we want the FDA to develop a preventive strategy for reducing lead exposure in all foods,” he says. “Right now, they’re just not in a position to do that because they’re chronically underfunded, and have been for decades, particularly on the food side, and that makes it very difficult for them to summon the will to focus on this.”

What You Can Do

There are a few steps you can take to minimize your exposure to lead from cinnamon and other sources:

Buy cinnamon with the lowest lead levels in CR’s tests. If you’re a cinnamon lover who consumes it daily, or who uses a lot of it when you do eat it, your best bet is to choose from the six products in our tests with lead levels close to 0 ppb. You can have a teaspoon or more of these a day—in some cases a lot more. For example, you can consume up to 6 teaspoons of Sadaf cinnamon powder. For 365 Whole Foods Market Organic cinnamon, you can have 16 teaspoons.

Consider sticking with mainstream brands. Of the 12 cinnamon products CR’s experts say to avoid because of concerning lead levels, 10 are from relatively unfamiliar brands sold mainly in small markets specializing in international foods. The same is true for all 17 cinnamon products that the FDA recently warned consumers about. (Consumers should check their homes for these products and throw them out.) By contrast, four of the six products with the lowest amounts of lead came from more familiar national brands.

Don’t rely on labels like “organic” or rely on where the cinnamon comes from. The six organic products in our test did come in below 1 ppm, and three actually had levels close to zero. But, Rogers says, “we don’t have enough data to say for certain that organic cinnamon, in general, is lower in lead.” And he says that the Department of Agriculture’s organic standards don’t include heavy metal testing. Selecting cinnamon based on where it comes from is no guarantee either. Our tests included cinnamon from many of the areas that grow it. “We found high and low lead levels in products from each location,” Rogers says.

Be cautious about bringing cinnamon home from travels abroad. Heavy metal levels, including lead, can be even higher in spices outside the U.S. One issue is that U.S. companies may import the highest-quality cinnamon, says CR’s Ronholm, which could leave lower-quality versions to be sold in the country of origin.

Be wary of taking cinnamon as a health aid. Studies showing possible health benefits from cinnamon, such as lowering blood sugar or inflammation, involve taking higher amounts than what’s typically used in cooking and baking—up to 3 teaspoons. That’s 12 servings of cinnamon. (A serving is ¼ teaspoon.) That would be okay with only a few of the very best cinnamons in our tests.

Limit your potential exposure to lead from all sources. This is especially important if you have kids at home because children are more vulnerable to the effects of heavy metals. One major route of exposure can be drinking water. CR recommends testing your water for lead and arsenic and, if levels are high, installing a water filter. For young children, see CR’s advice on choosing juices and baby foods low in heavy metals.

Vary the foods you eat. Switching up your diet may help you avoid overconsumption of lead or other heavy metals from any one food or spice. In addition, it will help ensure that you get enough vitamin C, as well as minerals like calcium, iron, selenium, and zinc, all of which can reduce how much lead the body absorbs.