AUSTIN, Texas — (The Texas Tribune) Liany Serrano Oviedo crouched in her yellow graduation dress, stared at the mirror and carefully blotted her tears with a wipe. It was a rare moment for the 22-year-old University of Texas at Austin senior to be alone and gather her composure.

Serrano Oviedo had been in high-performance mode all Thursday morning, making laps to get everything ready for the Latinx graduation ceremony she planned, sometimes breaking out into a jog to get from one side of the venue to another.

But she had a moment of frailty while talking with a donor who helped sponsor the event. All of her hard work in the last four years — getting her degree and organizing Thursday’s ceremony — was for her Venezuelan parents, she said.

“This graduation is a big deal because a big chunk of it is bilingual,” Serrano Orviedo said. “And my mom's English isn't that great. And so this ceremony is one where I know 100% she's understanding everything that's being said.”

For decades, subsets of Texas college graduates — from Latinx to LGBTQ students — have organized intimate events separate from the larger commencement ceremony to celebrate the completion of their degrees in the context of their identities and cultural heritage.

But this is the first year UT-Austin and other Texas public universities cut funding and staff support for such ceremonies in response to Senate Bill 17, a new state law that bans diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

Students across the state like Serrano Oviedo fought tooth and nail to rescue cultural graduations, often taking on the burden of planning and finding funding for the ceremonies. The Latinx graduation ceremony took place days before UT-Austin’s commencement, which will be held Saturday.

“It doesn't matter how many obstacles you're going to throw at our community,” said Serrano Oviedo. “We're still going to thrive and we're going to find other ways.”

Students take the lead

For years at UT-Austin, thousands of Latino family members would pack the on-campus Gregory Gymnasium at the end of the school year to see their graduates walk the stage. Some graduates used to wear serape soles made of traditional Mexican cloth. It was the only ceremony where the program was read in English and Spanish.

The now-defunct Multicultural Engagement Center would also pay for surprises for the families, like live Latin bands and food and floral decorations that matched the serapes.

But to comply with SB 17, public universities in Texas have shuttered the multicultural centers that used to organize cultural graduation ceremonies like the Latinx celebration.

Lawmakers who supported the passage of SB 17 last year argued that DEI programs and training were indoctrinating students with left-wing ideology and forced universities to make hires based on their support of diversity efforts rather than on merit and achievement.

The ban did not stop students in the graduating class of 2024 from organizing their own event. Serrano Oviedo and other seniors raised $9,000 with help from Latino leaders across the state. Austin City Council Member José “Chito” Vela secured a local performing arts center for the students to host the ceremony off campus. The League of United Latin American Citizens, the oldest Latino civil rights group in the U.S., stepped in to pay for that venue.

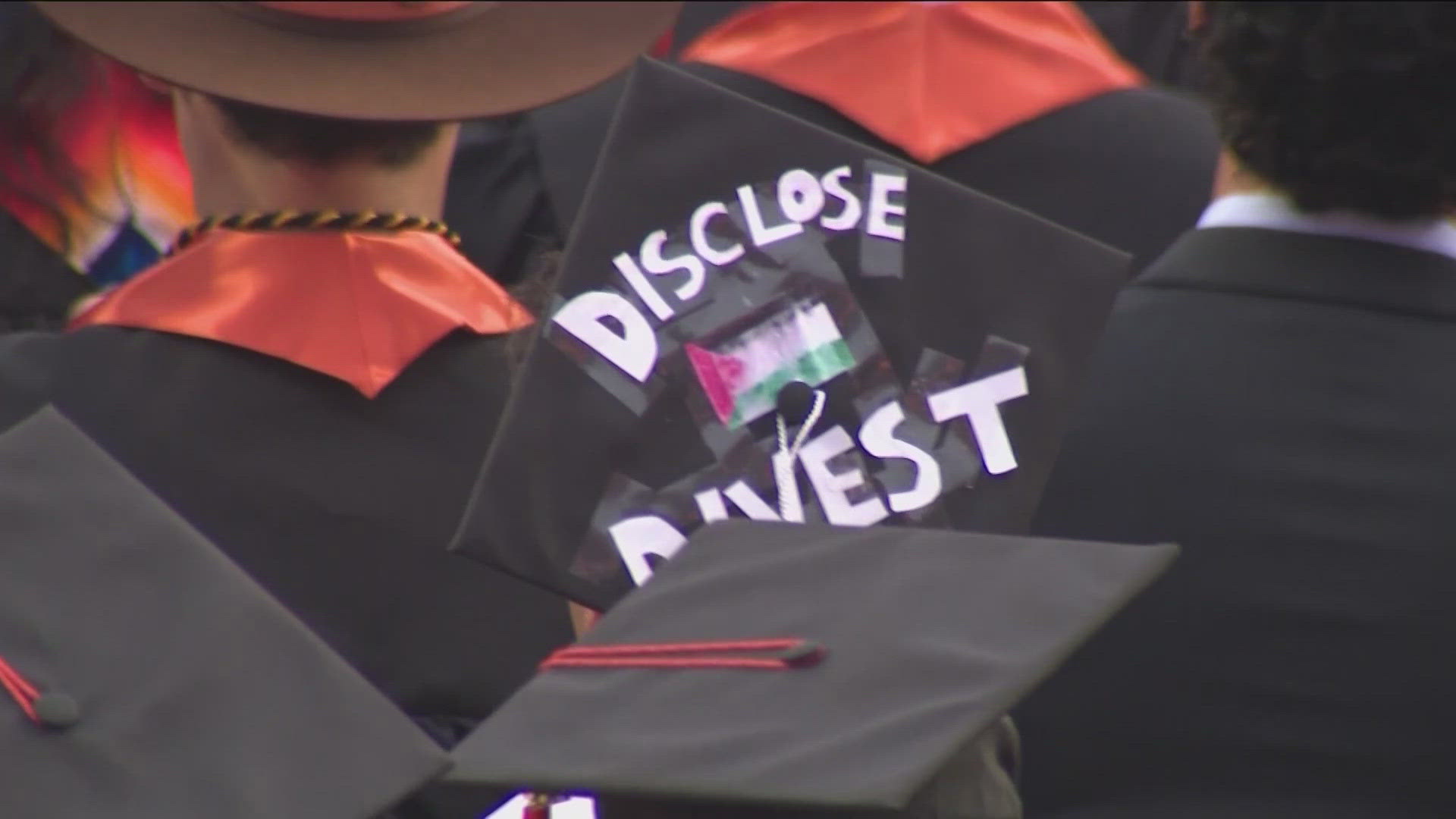

Students graduating this year have already been shaped by a unique set of global and political forces. Many of them graduated high school and entered college in the thick of the pandemic, which means they missed out on a formal ceremony back then. And now they’re leaving at a time where pro-Palestinian protests have broken out across campus, including UT, leading to dozens of student arrests.

On Thursday, as UT-Austin history professor Emilio Zamora adjusted the satin hood for one student at the Latinx ceremony, he called the survival of the tradition “a declaration of independence” from public institutions.

“These students are demonstrating they will have the final say,” he said. “It is a demonstration of our resilience. The university has failed us, but we have risen to the occasion with our youth.”

A nod to family

Under the pink and purple lighting of the nearly-full auditorium, parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles clapped, cheered and clapped again.

Cultural ceremonies often elevate themes that are important to those groups of students — like family to the Latinx community — and aren’t always part of university-wide graduations.

“Gracias a mi mami y papi”— “Thank you to my mother and father” in Spanish — one students’ graduation cap read. Another one read, “Sus sacrificios y apoyo son la razón por la cual lo logre”: “Your sacrifices and support are the reason I made it.”

For some students and faculty, celebrating the accomplishments of Latinx students is a critical recognition of the hard road they journeyed on to get their degree. Latino college students are often the first in their family to get a college degree. That makes cultural ceremonies, which acknowledge the generational sacrifices and obstacles that families have overcome, all the more significant.

They’re also an important gesture if Texas universities want to continue to recruit, retain and graduate Latino students, supporters say.

Despite being designated a Hispanic-serving institution, UT-Austin’s enrollment still lags behind in representing the state’s makeup. Hispanic residents represent the biggest share of Texas’ population — 40% — but only about 25% of students at UT-Austin are Hispanic.

“The cornerstone of a successful Texas is to be doing all of [these cultural events]. In essence, it’s going to affect academics and how people of color perceive the state,” said Katherine Ospina, a UT senior who raised the funds to pay for the ceremony. “Texas is an extremely diverse state and we need to capitalize on that diversity.”

Domingo Garcia, the president of LULAC, the Latino civil rights group that covered the cost of the venue, said he worked two jobs to be the first in his family to graduate from college. Preserving cultural graduations in the face of the DEI ban sends a signal that Latino culture has a place in the state, Garcia said.

“People don't understand the sacrifices that parents, many of them working class, have made to have that son or daughter attend UT and what they've gone through to get to that place,” said Garcia, who is a former state representative. “To not be allowed to celebrate your culture, to celebrate who you're from and what your family's from, it's really immoral.”

Ospina said she could not let the class of 2024 be “lost in the ether” of a post-SB 17 reality.

On Thursday, as the last few family members filtered out of the venue with their graduates at the end of the ceremony, Serrano Oviedo balanced a stack of leftover orange cords and a plastic H-E-B bag.

Serrano Oviedo said she is trying to secure funding from the city of Austin for future ceremonies. A new round of students will have to step in to do the work of organizing, but she’s hopeful the tradition will continue.

“Everything the state Legislature and university threw our way, we overcame,” Serrano Oviedo said.

Ikram Mohamed contributed to this report.

The Texas Tribune partners with Open Campus on higher education coverage.

Disclosure: H-E-B and University of Texas at Austin have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune. The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy.