AUSTIN, Texas — The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed serious problems in five Central Texas jails in Travis, Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays and Williamson counties, according to a study by The Texas Justice Initiative and Texas Appleseed.

The two nonprofit groups spent months gathering information from inmates and staff at the five county jails.

Researchers sent a total of 3,500 surveys and got nearly 40% back – about 1,200. They also received 40 letters from inmates detailing conditions inside jails during the height of the pandemic.

Researchers were trying to get a sense of what it was like inside during the pandemic. They also looked at the best practices recommended by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

The conclusion?

"There was a lot of fear in these facilities," said Eva Ruth Moravec.

The Executive Director of the Texas Justice Initiative said that fear from inmates and staff stemmed from inconsistent policies.

Remember how much confusion there was about COVID-19 for the general public? Moravec said it was worse for those behind bars.

Key findings include:

- Lack of transparency in jail policies

- Inconsistent cleaning policies

- Inadequate mask policies

- Lack of access COVID-19 testing

- Obstacles to medical care

- Ineffective quarantine practices

"A lot of people reported having to wait for more than 30 days, sometimes 60 days, for a new mask they were wearing, like what should have been disposable masks for way too long. Often, the onus was on incarcerated people to ask for a new mask," Moravec said.

Moravec also pointed out that the five jails were inconsistent with their data about COVID-19 cases.

"It's hard to know exactly when they had to be reporting because the State was saying only report when you have cases, but when you see the lines just suddenly pop up, it's like, 'well, how did they get to that level?' You know, there had to been other days previously where there were maybe one case or two cases," Moravec said.

Moravec said it's important for data to be accurate because the public relies on it – especially inmates, staff and others who provide services inside the jails need to know correct coronavirus case numbers for their own safety.

She also pointed out the accountability factor. Moravec said many of the people in county jail are pre-trial, meaning they haven't had the chance to prove their case in court.

"So to think about the aftermath of like somebody who might die in a Texas county jail of COVID while they're waiting for trial? Do we deserve that? Do people deserve that or somebody who is accused of something? Is that fair? Or do we want more out of our facilities," Moravec said.

Moravec now hopes her research catches the attention of lawmakers and others who can make a difference. She said it's not a question of if another pandemic will happen, but when.

KVUE reached out to all the sheriffs in the five counties mentioned in the report.

Travis County sheriff, Sally Hernandez, sent the following statement.

"The COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating impact as our entire nation faced a crisis it hadn’t seen in decades. Jails and nursing homes were especially impacted, housing vulnerable residents in communal spaces. We knew we were fighting an invisible, potentially deadly enemy inside our buildings. It was of paramount importance to us that we take every single precautionary measure we could to make our jail facilities fortresses against the virus. We implemented a litany of safety measures, including an innovative plan for isolating arrestees who might be asymptomatic carriers until our medical staff could ensure they were virus-free, fully approved by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards.

Incarcerated people maintain the right to refuse COVID-19 testing, vaccinations and medical treatment. Our medical team managed this complex situation despite a significant percentage of patients declining to participate in measures that would identify and help limit the virus’s ability to spread. Remarkably, TCSO has experienced only 459 cases of COVID-19 among the inmate population throughout the entire pandemic. No inmates died, and none required hospitalization. Our medical team and housing managers did a tremendous job of staying on top of positive cases, isolating symptomatic patients and protecting the general population.

TCSO fully complied with Texas Commission on Jail Standards’ reporting requirements and further, proactively reported both our inmate and employee positive statistics in weekly press releases that continue today. Prevention methods were also released publicly. In fact, the Texas Commission on Jail Standards used our system as a model for jails across the state and we had the honor of helping our colleagues in many other counties find innovative ways to tackle this incredible challenge.

I appreciate the note that our efforts were valiant. I believe it’s true. The valiant men and women working in your Travis County Sheriff’s Office continue to give the highest level of care to those in our custody. I’m also grateful to the judges, prosecutors and arresting agencies who worked with us to keep the jail population as low as possible during this unprecedented event."

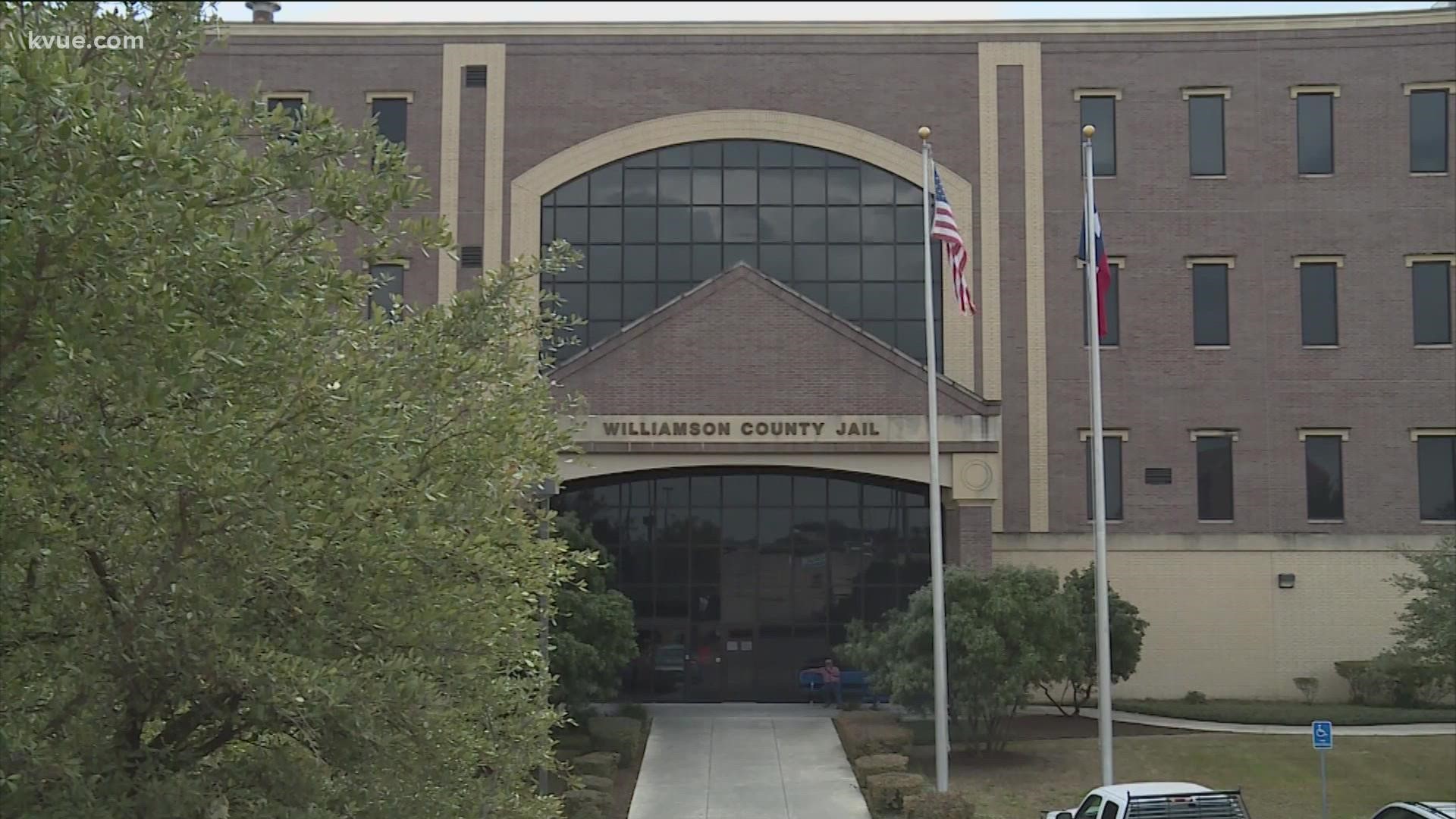

Williamson County Assistant Chief Deputy, Kathleen Pokluda, sent us the following statement:

"While I understand the goal of the Texas Justice Initiative’s report Infected with Fear is to help ensure that jails are held accountable for the treatment of jail inmates and staff, several points made in the report regarding Williamson County are not accurate or are indeed flat out false. I cannot attest to the position of the administration prior to January 1, 2021, but I can assure you that since Sheriff Gleason has been in office, we have made every effort to institute or maintain policies and procedures that best protect our staff and inmates, per CDC guidance and local health ordinances. I also cannot attest to any of the other counties mentioned in the report, these rebuttals are only in regards to Williamson County.

In response to their not being a written policy for Williamson County in regards to inmate access to soap and water (Table 3 and Table 25), that is a basic Texas Commission for Jail Standard (TCJS) policy that must be maintained in order to be in compliance. Any further policy written would be redundant since we are under the jurisdiction of the TCJS and violation would put us automatically out of compliance. Access to soap and water was and continues to be abundant and free. Access to paper towels and toilet paper (in place of tissues) has never been impaired and additional supplies have always been available upon request. Hand sanitizer was provided and is still available at officer stations upon inmate request. Soap was distributed by an officer into the pods weekly, more available upon request if the inmates ran out before the weekly replenishment occurred. Handwashing was and still is encouraged. Even during the winter storm in February, the jail was never without water.

Regarding cleaning and sanitation procedures (Table 5) jail staff cleaned and continue to clean the common areas several times a day. Beginning in March 2021, every 14 days, a special surface protectant and fogger are used that create an antimicrobial barrier that lasts for 30 days. Jail population that was in quarantine and isolation were given cleaning supplies at least 2 times a day or more upon request.

It is my understanding that there was an issue with inmates being charged for masks (paragraph under Table 11) at the very beginning of the pandemic, in early 2020, but it is also my understanding that the policy was changed. As I previously stated, I cannot attest to what the previous administration did or did not do. To my knowledge, this had not been an issue for several months leading up to Sheriff Gleason taking office in January 2021, inmates continue to be given masks free of charge and may exchange for a new mask at any time upon request. I am unaware of any inmates going over 30 days without getting a mask replacement or any claim that refusing to wear a soiled mask resulted in disciplinary action for any inmates.

In Table 13, only 38% of Williamson County jail staff reported that they were given regular access to face shields, but any individual who requested a face shield was given one.

Inmates were not charged for COVID-19 testing at any point during the pandemic (Table 14) nor for any OTC medications that were part of their COVID-19 treatment protocol. Per jail policy, if their medical care was for something other than COVID-19, appropriate charges were placed on their account. Inmates were tested for COVID if they displayed or verbalized symptoms. If someone in the tank became positive for COVID-19, inmates were tested upon request, and only with consent. After 10 days, if asymptomatic, individuals were moved out of isolation per CDC policy at the time, the chance of them transmitting COVID-19 to others was thought to be very low. Inmates were kept isolated until symptoms resolved.

Table 16 and Table 17 deal with inmates reporting whether or not they were tested for COVID-19. Upon intake, medical staff would request to test the inmate, regardless of symptoms. The majority of inmates refused, probably due to inmates wanting to avoid isolation. Avoidance of isolation may have also been a factor in whether or not inmates requested a test. We are unable to perform any medical procedure on an inmate without their consent, as that is a violation of their constitutional rights. In regard to the jail staff, temperatures were checked daily and symptom screening was completed upon reporting for work. There was no testing of employees unless requested due to symptoms or fear of exposure but working in a jail presents its own inherent risks and staff are aware of that from the beginning of their employment.

Specific staff was assigned to the isolation and quarantine areas and this staff was limited for the duration of the shift (Table 21).

Table 23 and Table 24 contradict each other in that Table 24 states that 82% of inmates reported that the medical care they received was adequate if they acquired COVID-19, but then Table 23 states that 79% say they did not receive medical care. I have no way to account for this discrepancy except that this is self-reported by inmates, is completely subjective and cannot be substantiated or supported in any way.

The quotes towards the end of the report are inflammatory and without further details regarding specifics of the complaints or concerns, the aim must be to create a false narrative of what was occurring in the jail. Inmates that were found to have COVID-19 were monitored carefully, and any inmate who needed further treatment was transported to the emergency room."

Hays County Sheriff, Gary Cutler, said that he takes issue and has concerns with the study. He also pointed out there are a lot of inaccuracies.

Caldwell County and Bastrop County did not respond.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: