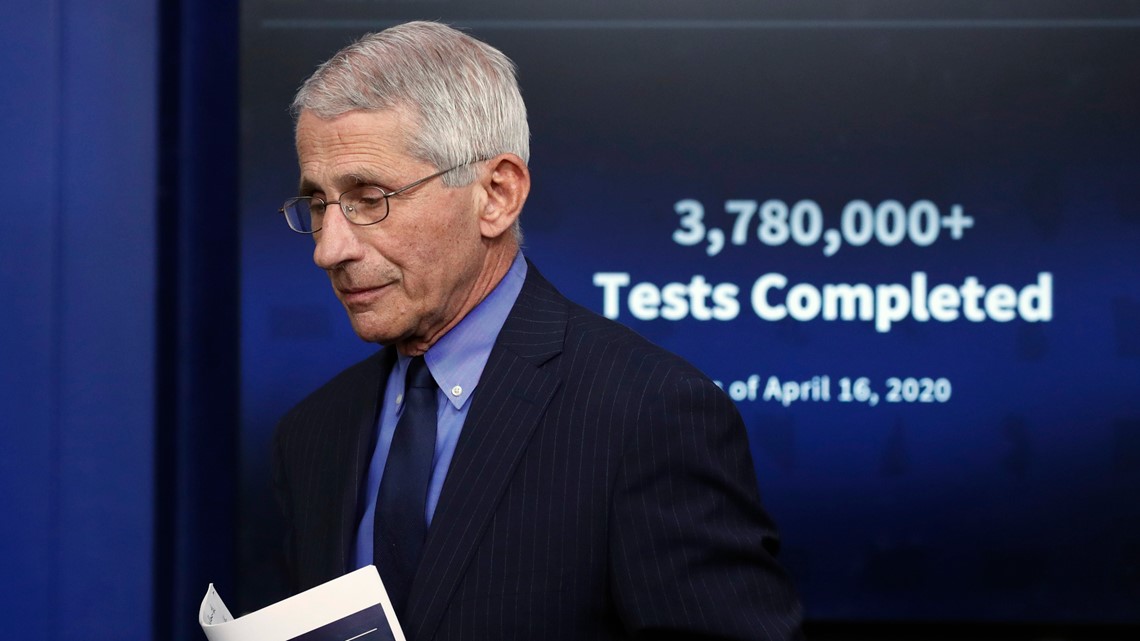

WASHINGTON — Dr. Anthony Fauci, the government's top infectious disease expert, warned on Tuesday that “the consequences could be really serious” if cities and states reopen the U.S. economy too quickly with the coronavirus still spreading.

More COVID-19 infections are inevitable as people again start gathering, but how prepared communities are to stamp out those sparks will determine how bad the rebound is, Fauci told the Senate Health, Labor and Pensions Committee.

“There is no doubt, even under the best of circumstances, when you pull back on mitigation you will see some cases appear,” Fauci said.

And if there is a rush to reopen without following guidelines, “my concern is we will start to see little spikes that might turn into outbreaks,” he said. “The consequences could be really serious.”

In fact, he said opening too soon “could turn the clock back,” and that not only would cause “some suffering and death that could be avoided, but could even set you back on the road to try to get economic recovery.”

Fauci was among the health experts testifying Tuesday to the Senate panel. His testimony comes as President Donald Trump is praising states that are reopening after the prolonged lockdown aimed at controlling the virus's spread.

Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn, chairman of the committee, said as the hearing opened that “what our country has done so far in testing is impressive, but not nearly enough.”

Worldwide, the virus has infected nearly 4.2 million people and killed over 287,000 — more than 80,000 in U.S. alone. Asked if the U.S. mortality count was correct, Fauci said, "the number is likely higher. I don’t know exactly what percent higher but almost certainly it’s higher.”

Fauci, a member of the coronavirus task force charged with shaping the response to COVID-19, testified via video conference after self-quarantining as a White House staffer tested positive for the virus.

With the U.S. economy in free-fall and more than 30 million people unemployed, Trump has been pressuring states to reopen.

Fauci, in a statement to The New York Times, warned that officials should adhere to federal guidelines for a phased reopening, including a “downward trajectory” of positive tests or documented cases of coronavirus over two weeks, robust contact tracing and “sentinel surveillance” testing of asymptomatic people in vulnerable populations, such as nursing homes.

A recent Associated Press review determined that 17 states did not meet a key White House benchmark for loosening restrictions — a 14-day downward trajectory in new cases or positive test rates. Yet many of those have begun to reopen or are about to do so, including Alabama, Kentucky, Maine, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Utah.

Of the 33 states that have had a 14-day downward trajectory of either cases or positive test rates, 25 are partially opened or moving to reopen within days, the AP analysis found. Other states that have not seen a 14-day decline, remain closed despite meeting some benchmarks.

Besides Fauci, of the National Institutes of Health, the other experts include FDA Commissioner Dr. Stephen Hahn and Dr. Robert Redfield, head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — both in self-quarantine—and Adm. Brett Giroir, the coronavirus “testing czar” at the Department of Health and Human Services.

The event Tuesday got underway in the committee’s storied hearing room, but that’s about all that remained of the pre-pandemic way of conducting oversight. The senators running the event, Alexander and Democrat Patty Murray of Washington, were heads on video screens, with an array of personal items in the background as they isolated back home.

A few senators, such as Alaska Republican Lisa Murkowski and Connecticut Democrat Chris Murphy, personally attended the session in the hearing room. They wore masks, as did an array of aides buzzing behind them.

The health committee hearing offers a very different setting from the White House coronavirus task force briefings the administration witnesses have all participated in. Most significantly, Trump will not be controlling the agenda.

Eyeing the November elections, Trump has been eager to restart the economy, urging on protesters who oppose their state governors’ stay-at-home orders and expressing his own confidence that the coronavrius will fade away as summer advances and Americans return to work and other pursuits.

The U.S. has seen at least 1.3 million infections and nearly 81,000 confirmed deaths from the virus, the highest toll in the world by far, according to a tally by Johns Hopkins University.

Separately, one expert from the World Health Organization has already warned that some countries are “driving blind” into reopening their economies without having strong systems to track new outbreaks. And three countries that do have robust tracing systems — South Korea, Germany and China — have already seen new outbreaks after lockdown rules were relaxed.

WHO's emergencies chief, Dr. Michael Ryan, said Germany and South Korea have good contact tracing that hopefully can detect and stop virus clusters before they get out of control. But he said other nations — which he did not name — have not effectively employed investigators to contact people who test positive, track down their contacts and get them into quarantine before they can spread the virus.

“Shutting your eyes and trying to drive through this blind is about as silly an equation as I’ve seen,” Ryan said. “Certain countries are setting themselves up for some seriously blind driving over the next few months.”

Apple, Google, some U.S. states and European countries are developing contact-tracing apps that show whether someone has crossed paths with an infected person. But experts say the technology only supplements and does not replace labor-intensive human work.

U.S. contact tracing remains a patchwork of approaches and readiness levels. States are hiring contact tracers but experts say tens of thousands will be needed across the country.

Worldwide, the virus has infected nearly 4.2 million people and killed over 286,000, including more than 150,000 in Europe, according to the Johns Hopkins tally. Experts believe those numbers are too low for a variety of reasons.