AUSTIN, Texas — While most Central Texans wait to get the COVID-19 vaccine, history tells us that getting everyone vaccinated doesn’t always happen right after a new drug is developed. Take the case of the polio vaccine in the 1950s.

Back then, the poliovirus struck fear in parents everywhere as children were most susceptible to catching it. The virus that caused polio often led to paralysis, breathing difficulties and, occasionally, death.

In 1952, during the worst polio outbreak in U.S. history, 57,000 people were infected, 21,000 were paralyzed and 3,100 died – most of them children.

Scientists worked to find a vaccine. Dr. Jonas Salk believed he had found the formula that would offer protection for the most vulnerable. It used a live virus that was killed in formaldehyde and injected into the arm to trigger the immune system to fight off a polio infection.

To test the effectiveness, volunteers inoculated nearly two million children, some with the real vaccine and others with a placebo. The results were made public in April 1955: the vaccine was about 80% to 90% effective.

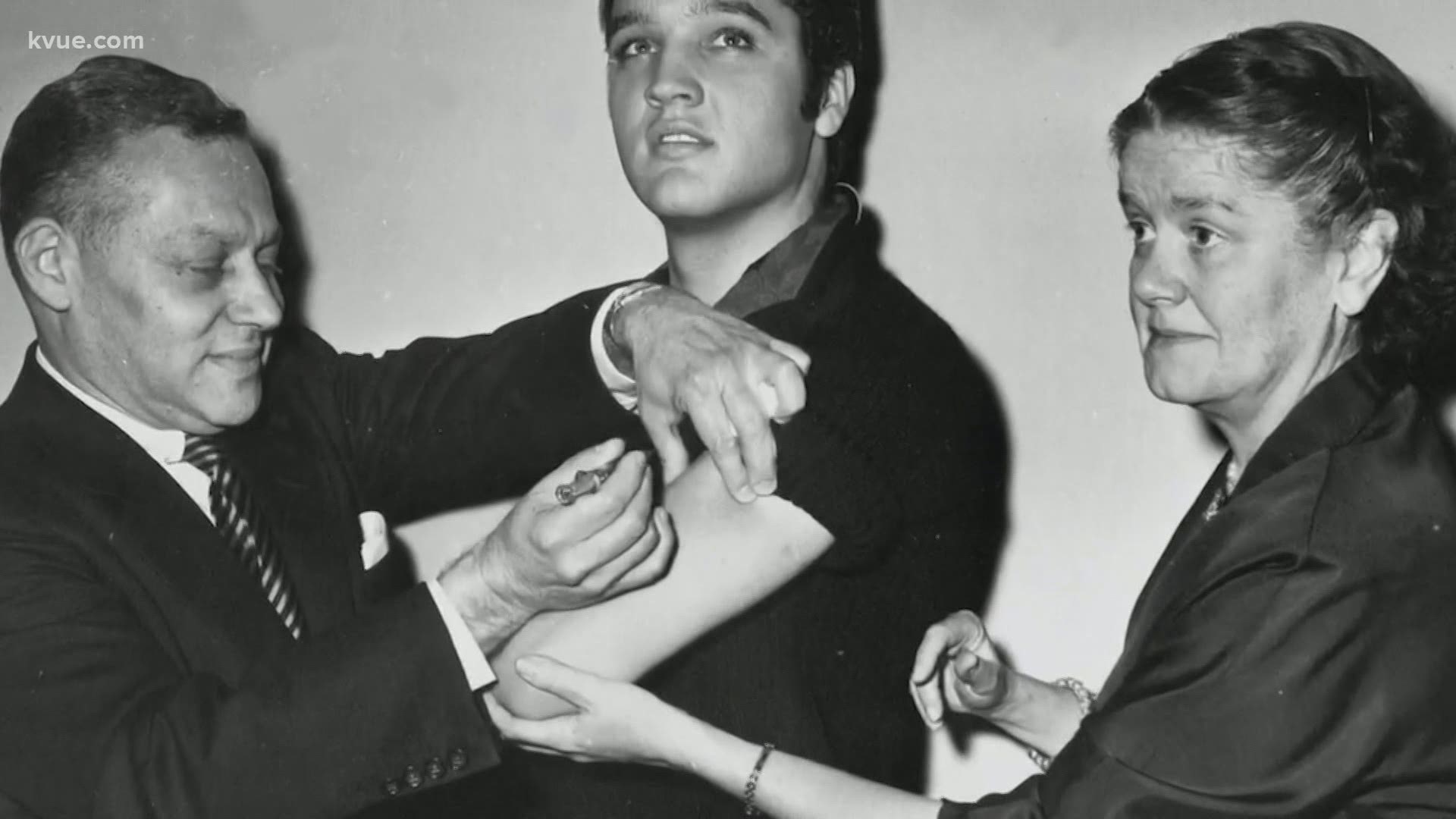

To offer reassurance that it was safe, publicity pictures showed Elvis Presley getting one of the first shots.

But getting a large number of people immunized would take time. There were critical shortages of the vaccine and public frustration. The government did not stockpile the drug and saw vaccine production and distribution as the responsibility of private pharmaceutical companies. It would take several years to reach everyone.

There was also a disastrous error that temporarily stopped the program. One of the six pharmaceutical companies licensed to make the vaccine accidentally failed to kill the live poliovirus before it was distributed. Instead, hundreds were injected with the virus. Many got sick and some died.

Once the problem was found, vaccinations resumed.

The incident led to a search for a different kind of vaccine. In 1961, Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral vaccine earned the recommendation of the American Medical Association after extensive worldwide testing.

Across the U.S during the early ’60s, people lined up to swallow simple sugar cubes that had been coated with a weakened live poliovirus. It was remarkably effective at stopping the spread of polio and protecting the individual from future infections.

Today, the Salk and Sabin vaccines are credited with leading to the virtual eradication of polio worldwide.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: