Defenders: Why Central Texas development may be partly to blame for toxic blue-green algae

The toxic blue-green algae found in several Central Texas waterways could be a deadly side effect of the area's booming growth.

The lure of Austin's lakes and recreational lifestyle contributes to its growth. But for all the fun and beauty our waterways bring, there is also a danger: toxic algae killing pets.

And it's not just happening in the summer months.

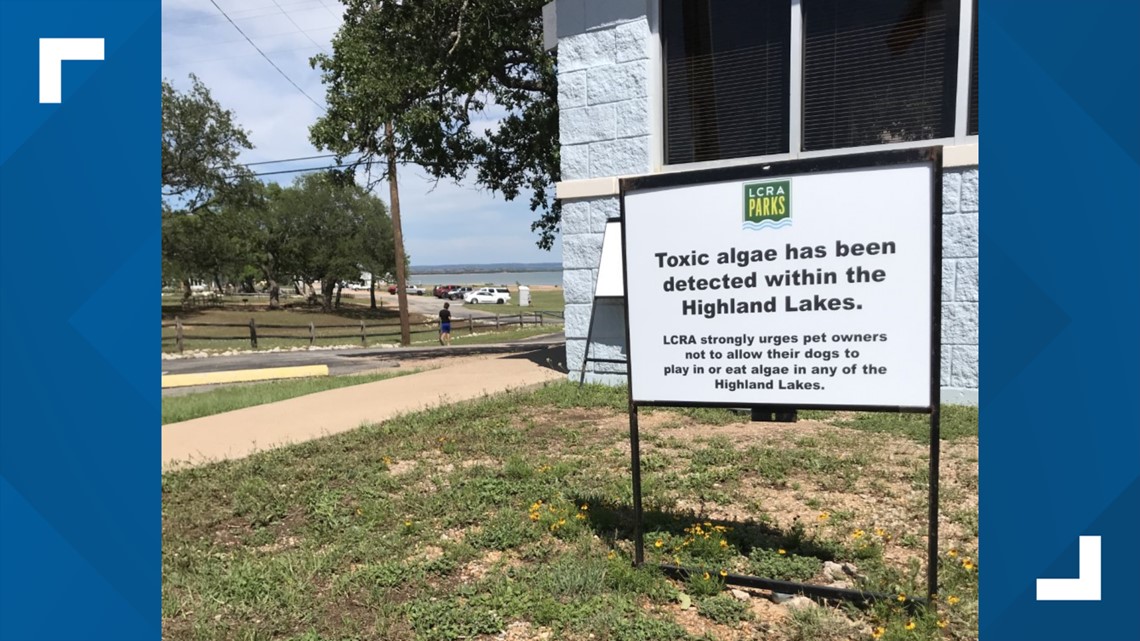

Back in the summer of 2019, several dogs died after visits to Austin-area lakes, where they ingested blue-green algae. It happened again right after the snowstorms this winter. The Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA) found the same toxic algae in several of the Highland Lakes.

Turns out, it could be a deadly side effect of our booming growth.

Deadly day at the dog park

A backyard game of fetch brings so much joy, yet so much sorrow for Claire Saccardi. It brings back a flood of memories of what happened two years ago after a quick trip to the dog park at Red Bud Isle.

She was with her golden retriever, Harper, her companion for four years. They were inseparable.

"She was chasing balls and sticks in the lake and coming back," Saccardi said.

An hour later, back home with Harper, Saccardi realized something was wrong.

"She's walking down the kitchen aisle and just trips and falls and collapses," Saccardi said.

She managed to get Harper to the living room, but the dog could not stand up on her own. So, Saccardi rushed her to an emergency vet.

"I remember them coming in and saying, 'Your baby is not doing well. Can we give her CPS?' and of course I said yes, but that's when I knew that it wasn't going to be OK," she said. "It was fast."

Harper died from ingesting toxic blue-green algae, according to the vet. She was one of five dogs to die that summer in Austin.

Then in January, it happened here again. Another dog dead, this time after playing in Lake Travis and ingesting blue-green algae.

“I thought we were the last ones,” Saccardi said.

Brent Bellinger is an environmental scientist senior for the Austin Watershed Department. He performs a lot of the testing on the local lakes.

“I've gone out, taken samples from Lake Austin and Lady Bird Lake. We did have a hit for that same toxin in Lake Austin by Mansfield Dam, the low water crossing there, but Lady Bird Lake has so far come back negative,” he said.

Blue-green algae are actually a type of bacteria known as cyanobacteria. It typically grows in areas where there are high levels of phosphorous and nitrogen and when water becomes still and warm – but not always.

"These cyanobacteria are present year-round. They just tend to crank up their growth rates during the hottest part of the year," Bellinger said.

That’s what concerns the watchdog group Save Our Springs Alliance.

"When it happened this year, it happened right after one of our historic freezes. So it's not necessarily just the heat that is causing the concern and the growth of the blue-green algae. There are other contributing factors that are obviously in play," said Bobby Levinski, an attorney with Save Our Springs Alliance.

"It's a confluence of conditions. Obviously, development contributes more sediment, more runoff, more nutrients, and that helps fuel cyanobacteria growth, like zebra mussels. From what we've heard, each lake that has mats has zebra mussels," Bellinger said.

The invasion of zebra mussels is a factor because they filter out the good bacteria and leave the bad, helping toxic algae grow.

"When you have a population that's growing so fast – that's what we have in Central Texas – it's very, very difficult to limit the amount of nutrients getting into these water bodies. So, that's where we are right now,” said Mike Clifford, technical director for the Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance.

Clifford said another contributing factor is the growing amount of treated wastewater discharges that the KVUE Defenders have reported on for years, and all the development happening in our area.

"We have a lot of nutrient sources now coming into the water – wastewater treatment plants, agricultural runoff, septic tanks, things like that – that are upstream," he said.

"One of the things that we do need to address in the future is, as we are growing as the region, what water quality standards are [we] holding developers to [to] ensure that the water gets treated before it makes its way back into our water systems?" Levinski said.

Are people at risk too?

"As long as people aren't directly interacting with the algae, their risk and their concern should be low. Obviously, this isn't potable water – you don't want to be ingesting the water anyway," Levinski said.

The LCRA said blue-green algae toxins can cause skin and eye irritation or rashes. Severe reactions can occur when large amounts of water are ingested and can include diarrhea, cramps, vomiting, fainting, dizziness, numbness or tingling in your lips, fingers and toes. If you are experiencing these symptoms after swimming, you should call your doctor.

Environmental advocates said the algae could impact our drinking water if we're not prepared.

"One of the concerns about it making its way into our water supply is how much is making its way in there to know whether our treatment methods are going to be sufficient to make sure that we have safe drinking water. There are communities such as the City of Toledo that actually had to shut down their entire drinking water operations because they had too much cyanobacteria built up into their lake system," Levinski said.

In fact, in 2014, there was so much toxic green algae in Lake Eerie that the water system in Toledo, Ohio, was shut down. The algae were visible from the air.

Austin Water told the KVUE Defenders that it "has processes in place to remove cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins and, so far, cyanotoxins have not been detected in any of our plant intakes."

Can we get rid of blue-green algae?

Certain chemicals can eliminate the algae, but those present even more environmental issues. Aeration has been proven to work, but it can be expensive and difficult in large bodies of water.

Matt Atwood of Lonestar Life Sciences has a different solution.

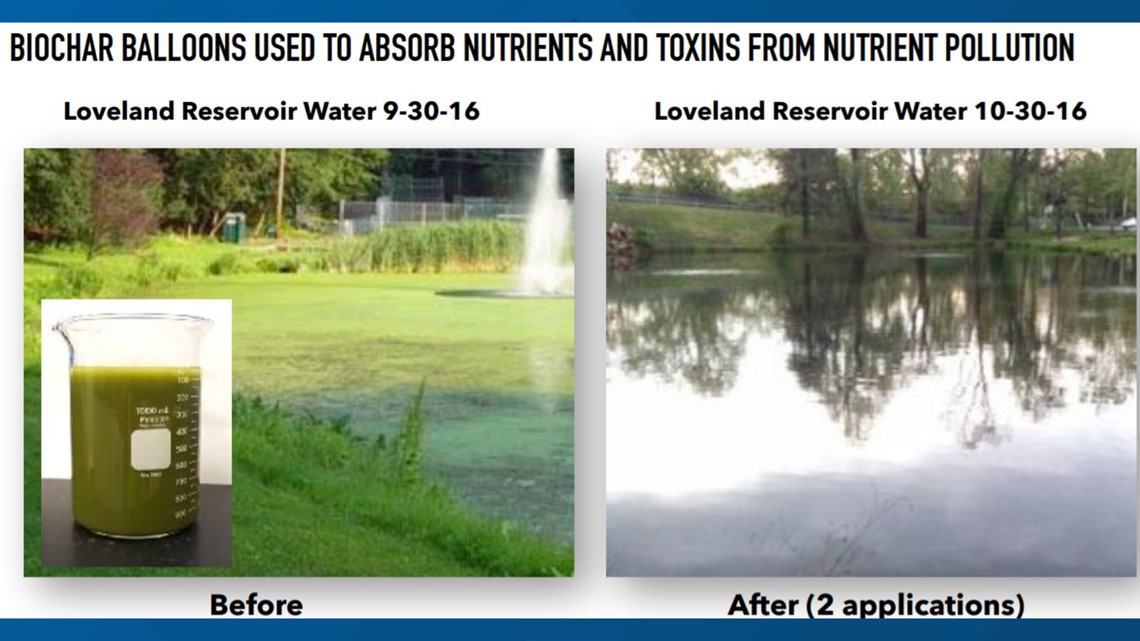

"This is an example of a biochar sock," said Atwood, showing a black sock filled with biochar. "We had the solution that we presented two years ago by putting biochar in the water and then you filter that water out.”

Biochar is a charcoal-like substance made from burning organic material like trees. It is then put into socks and dropped into the water.

"If you can put the biochar in the current, and especially where the water comes into the lake, then we can control the nutrient pollution immediately. We can definitely drop that down. And when you drop the nutrients that are in the water, you're going to have fewer algae growth. So that's our easiest solution, is to take care of it naturally and not have to challenge chemicals with other chemicals," Atwood said.

Biochar is not a new invention. In fact, it's been used in agriculture to improve soil fertility and agricultural yields.

However, Atwood has patent-pending technology for use on blue-green algae and is working with Texas A&M University to study its effects in Uvalde, Texas.

"We've done projects on lakes, reservoirs, small ponds, agricultural ponds, and it only takes 30 to 45 days to completely clean water," he said. "So it doesn't take very long. It's a fast-acting product and it's a natural solution and the cost is under $100,000."

It is one of several solutions that the City of Austin is considering.

In the meantime, Austin has put up signs along some of the most heavily used waterways warning of the potential dangers. And the testing continues.

"You can look at algae but you can't tell if it's toxic or not, so it's best to keep your animals away from it and minimize your exposure to it," Bellinger said.

"I wouldn't let my dog go in these lakes right now with this going on," Clifford said.

As for Claire Saccardi, she has a new puppy named Charlie – and a new perspective.

"He does not go in water, period," Saccardi said. "It really changes what you do and how you live your life in the summer, I think, as a dog owner."

More research on blue-green algae

It is possible that the dogs that died ingested the blue-green algae when cleaning themselves after swimming, and bathing them after may not be enough to help. Saccardi said she gave her dog Harper a bath as soon as they returned home.

Veterinarians say blue-green algae are so toxic that most pet owners don't have time to get their pets to the vet.

You can learn more about blue-green algae in Austin on the City's designated page or on the LCRA's website.

The LCRA also continues to test Austin's waterways. The agency's most recent test on April 21 found the presence of blue-green algae still in Lake Travis.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: