Austin wants to be a model of modern policing, but the future remains unclear

A year ago, City leaders wanted to make Austin a national model in police reform. What has emerged is a fragmented picture of success.

A little more than a year ago, Austin leaders set out on a new mission in the aftermath of unprecedented protests: To make the city a vanguard of modern policing and create a template that could be replicated across America.

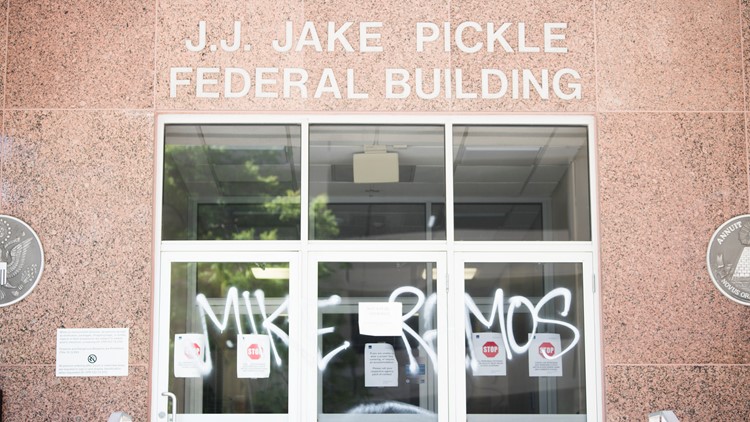

In the months following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the local controversial police shooting of Michael Ramos, council members cut or reallocated $140 million – about one-third – from the Austin Police Department's budget by removing operations such as 911 dispatch and the forensics lab from law enforcement oversight.

In what turned out to be among the most far-reaching decisions, officials also nixed three cadet classes, giving the department time to transition the police academy from a military-style boot camp to something that more closely resembles a college classroom. The cancellation meant that as more than 130 officers left in the past year, the department had no new rookies to replace them.

Officials also directed new money to programs to help address what they said were underlying causes of police interactions, including mental health.

All told, Austin at the time was among the biggest cities in the U.S. to remove that high of a percentage of the local police budget and to launch such a dramatic policing overhaul.

But recent interviews by the KVUE Defenders and the Austin American-Statesman with more than 30 City leaders, City Hall staff, activists, politicians and community leaders reveal Austin’s efforts to dramatically reform police have, in many ways, yielded a fragmented picture of success a year later.

Much of the discussion has become acutely political, with new laws passed by the Texas Legislature – primarily aimed directly at Austin – limiting cities from decreasing police budgets without the threat of losing tax dollars.

The discussion of police reform also has been infused with issues such as a rise in homicides and gun violence.

“The conversations in our community are ongoing to make sure that we have a public safety system and police force that makes everyone feel safe, and that’s the conversation we’re involved in,” Austin Mayor Steve Adler said in a recent interview. “There’s a lot of work to do.”

Austin remains in a unique moment for that continued discussion. The City is in the midst of hiring a new police chief. Voters in November will consider a measure pushed by the political action committee Save Austin Now that would mandate a minimum staffing level for the police department at an estimated cost of $119 million a year.

To help promote ongoing and fact-based dialogue, KVUE and the Statesman early in October will jointly host a community forum with panelists from all sides of the issues. The goal: To discuss the future of policing in Austin and the community’s goal of reform.

And, in the end, create a platform of discussion to help ensure that what happens in Austin will reflect policing for all.

A turbulent policing past, an uncertain future

Austin’s minorities for decades have had a tumultuous relationship with police – a past that activists such as Chas Moore know well.

“The history of policing in Austin, specifically when it comes to the Black community, has been very tense,” said Moore, the director of the Austin Justice Coalition, an organization that seeks equal treatment for people of color.

There were cases like the 2002 death of Sophia King, a mentally ill woman shot and killed by an officer as she was about to stab her apartment manager. The case revealed the need for more officer training when confronting people experiencing a psychotic break.

The next year, Officer Scott Glasgow shot and killed Jesse Owens after stopping him in a stolen car. Glasgow became entangled in the car, Owens started driving and Glasgow fired.

Until this January, Glasgow was one of only two officers in the past 20 years to be criminally charged in an on-duty shooting among more than 60 cases. The other was Officer Charles "Trey" Kleinert, who said his gun accidentally fired in July 2013 when he got in a tussle with Larry Jackson Jr., who he was investigating for possible bank fraud.

Judges dismissed both cases.

“I think policing in Austin historically has been, you know, I think it has been corrupt,” Moore said. “I think it has been unfair. I think it has been racist.”

Scott Henson, a criminal justice reform blogger, has lobbied local leaders to change policing for more than 20 years. Henson said that, for decades, activists were blocked by local politics – council members elected by a like-minded Central Austin voter base that Henson said were generally police supporters.

That started changing in 2014 when the city began electing district-based council representatives, giving reformers a new voice at City Hall.

“For the most part, criminal justice reform really couldn’t get any traction and was never a priority for our elected leaders,” Henson said.

Until last summer.

Activists presented to City leaders a plan to cut the department budget and reallocate millions in funds. Council members went on to vote on the cuts and reallocations in August.

But by the fall, with homicides and gun violence rising, and emergency responses taking an average of a minute and 30 seconds longer compared to a three-year average of seven minutes and 30 seconds, some Austin groups such as the Greater Austin Crime Commission, which supports law enforcement as a way to prevent crime, grew increasingly worried. They were frustrated the City had gone too far.

“I don’t think it was really an evidence-based approach to making some of these decisions last summer,” said Cary Roberts, the commission’s executive director.

Gov. Greg Abbott declared local police budgets an emergency item for new state laws for the 87th Texas Legislature. The Legislature went on to pass a measure blocking cities from getting state sales tax money if they took money away from police.

“The fact is, if we have lawlessness in our cities caused by local decisions that reduce law enforcement officers, it is going to cause chaos throughout the entire community,” Abbott said in a news conference.

The city has also seen the emergence of a new political action committee called Save Austin Now that says it is targeting city policies out of step with residents. In May, it successfully restored a ban on public camping after the city council removed it two years earlier.

Now, it is pushing a local ordinance on the November ballot requiring, among other things, that the department maintains a minimum number of officers based on population.

But the day-to-day operations of the department remain a local decision. And looking to the future, Austin still has not answered the most important question: What does it want its police force to do?

“We did survey research last summer and while the majority of Austin voters supported police reform, they did not support cutting cops when crime was rising and response times were slower,” Roberts said.

A study by the Austin Justice Coalition gives a roadmap for its goals. It calls for removing some duties from officers, such as no longer having them respond to burglary alarms, most of which turn out to be false.

A City task force to reimagine the police has also made several recommendations, including that police only respond to calls for service or assistance.

Moore said he thinks everyone should keep an open mind as the City looks to the future and help create a new mold for policing not just in Austin but across America. One, he says, that will protect – and serve – everyone.

“We need to be very, very serious about how we allow those people, those men and women in uniform, to do their job,” Moore said.

The crime discussion

In the past year, news of murders and gun violence have dominated Austin headlines as the city grows and confronts worries of “big city crime.”

To help curtail the violence, police have put new programs in place, including one announced in April to track down some of the city’s most dangerous offenders and illegal guns.

“I’ve said that this is a marathon and not a sprint,” Interim Police Chief Joe Chacon said.

But as Austin continues discussions of police reform, the conversation has become infused with concerns about crime among some in the community. Others say that crime is being used to amplify fears and to justify calls for more officers.

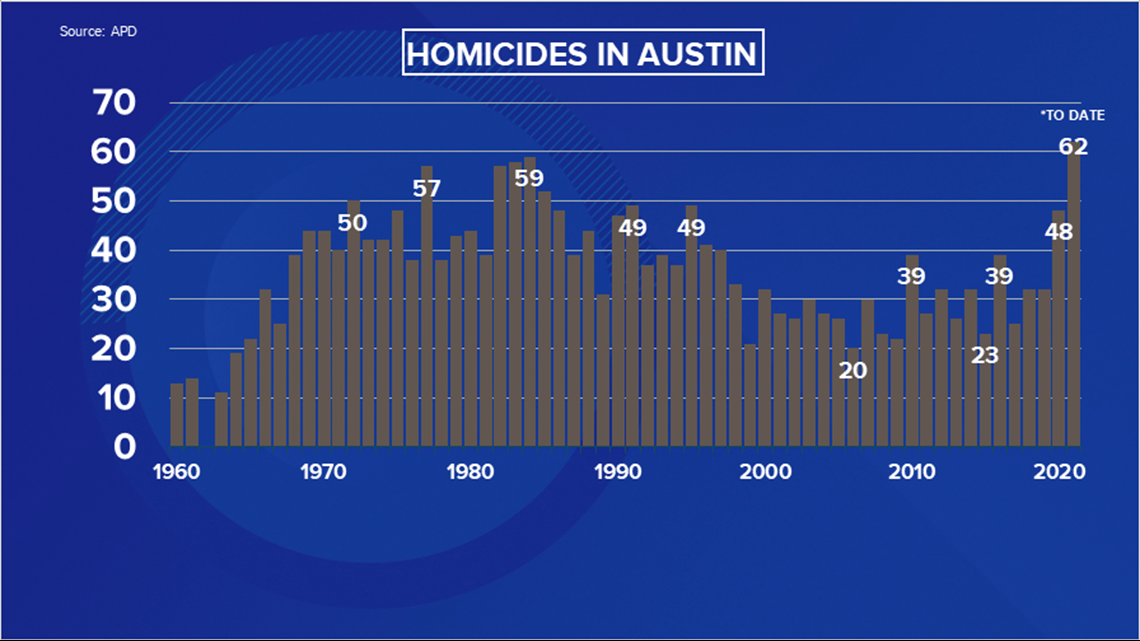

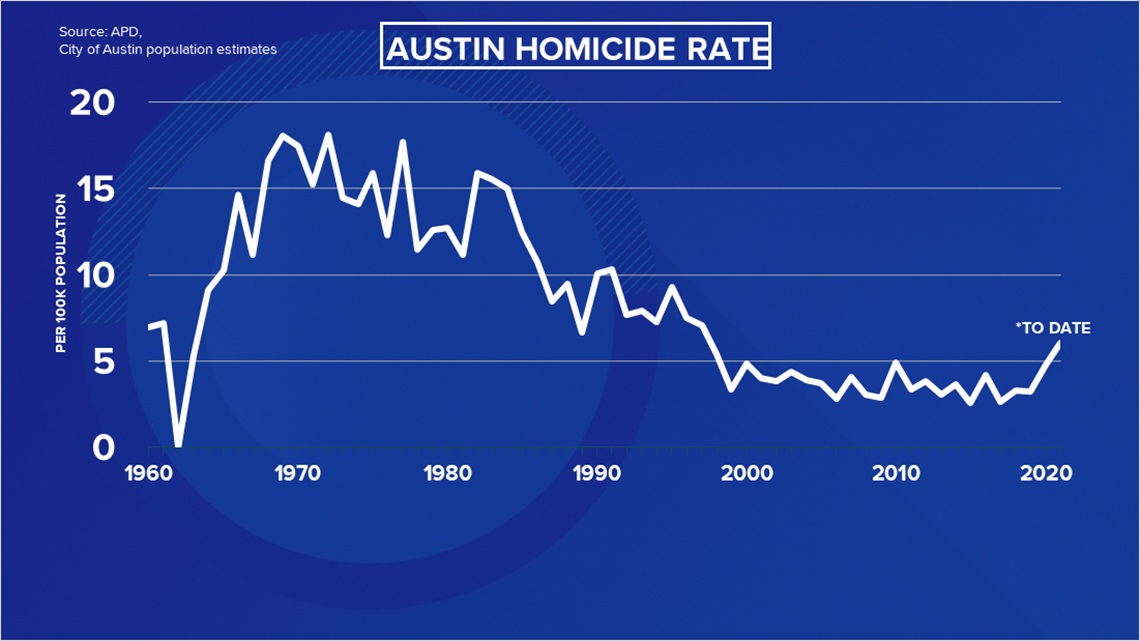

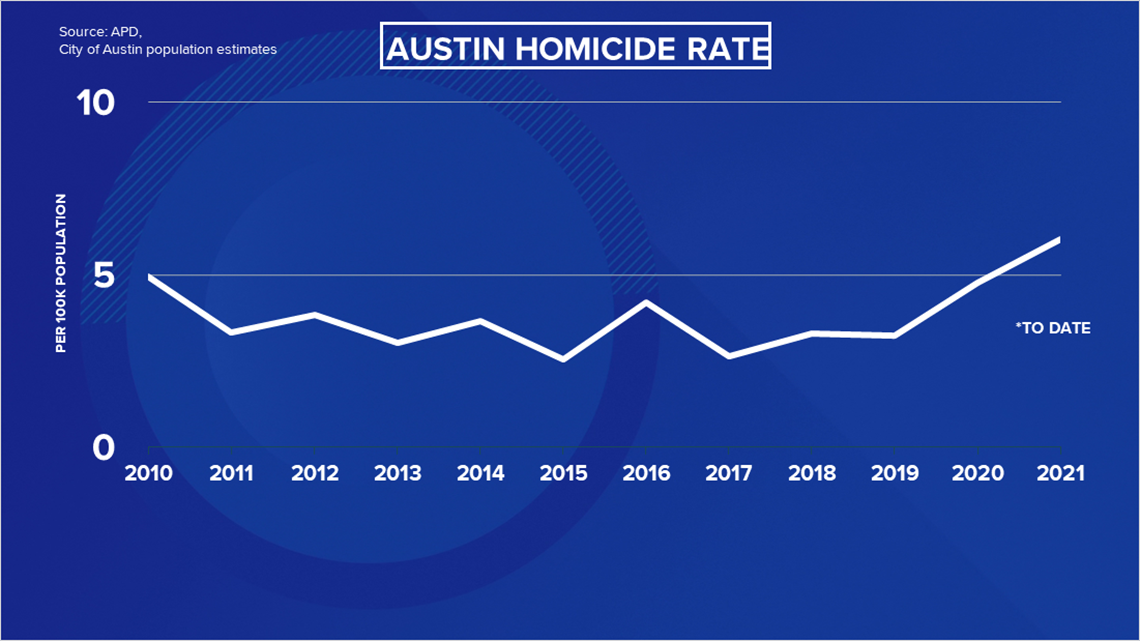

At the end of July, Austin had 48 homicides – more than in all of 2020, when the city recorded 49 in one of its deadliest years in decades. By mid-September, Austin had reached 60 homicides, the most in the 61 years that Austin police have kept records.

The rate of about 6.0 per 100,000 residents is the highest in the past decade, although it is less than half than in the mid-1980s when Austin experienced a three-year spike in homicides.

Aggravated assaults rose 15% from January to June 2021 compared to the same period last year.

And gun violence has been on the rise in the past five years, according to an APD report released in March. It shows guns used in crimes such as murder, rape, robbery and aggravated assault rose from 689 in 2015 to 1,546 last year. Gun crimes themselves – such as possession of a firearm by a felon – more than doubled from 503 in 2015 to 1,110 in 2020. Reports of stolen guns went from 864 to 1,016.

“I think it has to be a concern for all of us,” Mayor Steve Adler said. “We have to do everything we can to understand what the causes of that might be and to address them.”

Austin’s rise in murders and other violence also comes at a time when other violent crimes like sexual assault and kidnapping are holding steady. Property crimes are also staying relatively flat.

The city is part of a national trend for a rise in murders and shootings, even among those that have taken no steps to alter policing budgets or staff sizes.

Additionally, several major incidents recently have also renewed crime concerns.

Austin’s crime and policing policies became an issue in a June mass shooting that killed a New York tourist and injured 13 others. The family of Doug Kantor has said that they blame Austin’s policing policies in his death, even though police have said downtown was properly staffed that night.

Concerns about crime have also helped push a citywide vote in November. The PAC Save Austin Now is pushing a measure to make sure APD has at least two police officers per every 1,000 residents. Right now, the city has about 1.8 per 1,000.

Police supporters point out that the city council’s own consultants said in reports in 2015 and 2016 that Austin should hire at least 100 more officers to maintain safety and community policing goals. But others, including Austin police reformer Scott Henson, accuse officers and others of overstating crime and turning it into a political scare tactic to maintain a traditional model of policing.

“They’re pretending like Austin is some hellhole, unsafe city,” Henson said.

Chas Moore, director of the reform group Austin Justice Coalition, said some cities across the country have added or maintained the size of their police forces, only to see no real impact on crime.

“Just because you have the officers doesn’t mean that crime is going to be reduced and it doesn’t mean officers are going to be there,” Moore said. “Like, to me, after you call 911, the harm and the damage have already been done.”

Criminal justice experts say there is evidence to support arguments that more officers don’t necessarily lead to less crime. Others say what often matters is not how many officers a city has but what those officers are actually doing.

Meanwhile, the causes of the violence remain elusive.

John K. Roman is a senior fellow in economics, justice and society at the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center. What he calls a “violence epidemic” started around the same time as the COVID-19 pandemic. He attributes the spike to the pandemic itself.

“You have people with long-term trauma, long-term disputes, they are young men, they are not working, they are not in school. Their support institutions, their community centers, their churches, places they go, people they talk to for support, are closed. And so, you are left at home with all of the anxiety that we all feel,” he said.

But Roman said Austin needs a multi-pronged approach to preventing crime, including addressing other underlying issues like economic disparities.

“We need to understand that concentrated poverty in the same places, in perpetuity, and the hopelessness that creates for people who live there,” he said. “Ultimately, those are always going to be volatile places until we commit to trying to get people onto a path of more opportunity.”

Some officers depart, others remain

Chris Carlisle spent most of his 24 years with the Austin Police Department in the heart of downtown – first, on routine patrol, then as a burglary detective and rounding out his career on Sixth Street bike patrol.

“I’d come to work and they pay me to ride a bike and they pay me to talk to people every day,” he said. “I loved the interaction with the citizens, with even the transients and the business owners.”

The police corporal had been building a retirement plan that included leaving the department at the end of this year and moving his family to the Texas coast.

Then he worked on the frontlines through the unprecedented protests after George Floyd’s murder.

“I had frozen food thrown at me. I had frozen water bottles thrown at us,” he said.

And he watched public sentiment about his beloved profession shift from hero to villain in the weeks that followed.

“All of a sudden, no matter what we did, no matter how we did it, it was never good enough. And we were always the bad guys,” Carlisle said.

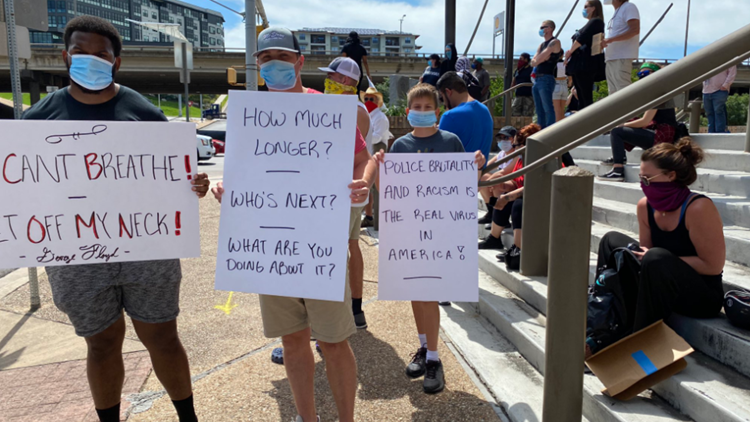

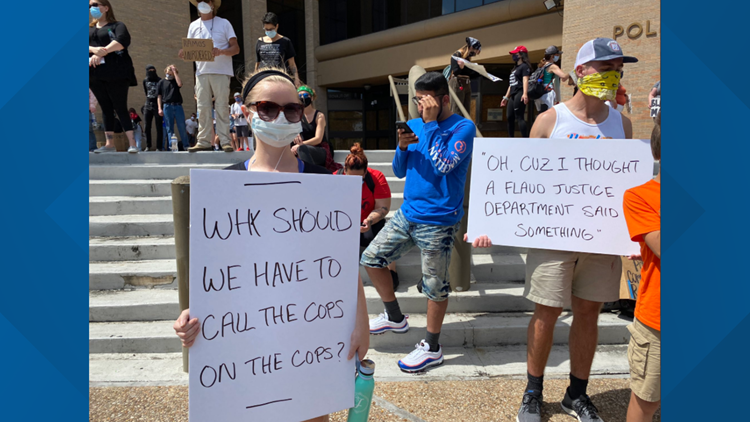

PHOTOS: Austin protests for George Floyd, Michael Ramos

He decided it was time to go. At 51 years old, he pushed up his retirement date to this past January.

In the 14 months since a national movement of police reform took hold in Austin, more officers have left APD than ever before. Many were like Carlisle: veterans eligible for retirement. Others were only on the force a few years and decided to abandon the profession altogether.

According to Austin police statistics obtained by the KVUE Defenders, the number of officers leaving the department reached 79 in mid-January and increased to 130 by the end of May. Of that 130, 64% were patrol officers, considered the backbone of the department.

In the past year, the department lost officers at a rate of 12.5 to 20 per month, compared to 7.5% in 2019. Six years ago, the rate was 4. By the summer, APD had 1,800 officers – about the same number it had in 2016.

Officials point out that the departures have come as officers who participated in larger-than-normal cadet classes in the late 1990s are now becoming eligible for retirement, likely also contributing to the attrition.

The departures have forced the department to pluck dozens of officers from specialty assignments until more can be trained and put on the street in coming months. Officials say the shifts were necessary to make sure officers are responding to the most serious emergency calls within the department’s three-year average of 7 minutes and 30 seconds.

Other departments nationally are grappling with departures as well. A survey this summer by the Police Executive Research Forum found a 45% increase in retirements and nearly a 20% increase in resignations among departments of all sizes compared to the previous year.

But public discussion about departures has often overlooked officers who have remained on the force. Many say they viewed the past year as a deeper call to action for better community relations – and to convince colleagues to get rid of an outdated policing playbook.

Officer Jeremy Bohannon has been on the force for nine years. In that time, the 38-year-old father has worked to bridge conversations between officers and the community. He, too, was on the front lines during last year’s protests – more of the same work he says he had already been doing in the neighborhoods he patrols.

“You get a front-row seat to society, pretty much,” Bohannon said. “And so, I love solving problems and helping people and, as a police officer, that is what you get to do on a daily basis.”

The vacancies from departures over the past year eventually will be filled by what officials hope will be APD’s future. Even at the time of national unrest and officers leaving the profession, APD received more than 2,000 applicants for a cadet class now underway – its most diverse class ever.

City leaders delayed the academy for more than a year, allowing its curriculum to shift from a military-style boot camp to something more like college classes.

Part of the effort is to include the community. At a June meet-and-greet with citizens, 100 cadets shared stories with residents about why they want to be Austin police officers.

Craig Campbell, a 29-year-old former Army soldier at Fort Hood, said he had always been interested in law enforcement growing up in Jamaica and living in New York.

Once he’s on the street, he says he plans to help change the culture of the department and public perceptions of policing – one interaction at a time.

“A lot of colored folks are against the cops, and I am like, ‘Who is going to look out for you if you are not part of the team?’” he said. “You only can make a change if you are part of a team. If you don’t, there is no change.”

A community discussion

Following the airing of this report, the KVUE Defenders sought answers to community questions on policing in Austin as part of an Oct. 4 town hall hosted jointly with the Austin American-Statesman.

Austin's path to police reform will likely continue to see a mix of success and shortcomings in the months to come, according to the panel of experts, but the city should continue to try to design a department that will meet the needs of all citizens.

Panelists were newly appointed Austin Police Chief Joe Chacon, former Travis County Sheriff and Austin Police Monitor Margo Frasier, and Paniel Joseph, director of the Center for Race and Democracy at the University of Texas.

In a wide-ranging conversation, each acknowledged that Austin likely hasn't yet become a national model for police reform – a goal that city officials set last summer – but said that it could help design new types of policing in the future.

"This is not something we have a blueprint for," Chacon said. "Have we gotten it right every single time? I don't think that we have, but we are certainly trying to figure our way through this."

Last year, Austin City Council members cut or reallocated about $150 million from the police budget and separated some operations from law enforcement oversight. The budget has since been fully restored because of a legislative mandate, but the daily functions of policing are still a local decision, and the community still has not decided what it expects from a modern police force.

Chacon said that although some have fought against reforms, such opposition is expected.

"We have to remember that abolishing slavery upset people in the 19th century too," he said. "There is going to be a reaction and we have to remember that."

Frasier said that while she appreciated the City leading efforts to make the Austin Police Department a national model, she was disappointed that some of the conversation missed important opportunities for unity.

"I was disappointed in the fact that what we wound up having was a lot of one-way communication where people were talking at each other instead of to each other," she said.

As the city looks to the future, Frasier said she is heartened that the City is revamping its police academy to make it less resemble a military boot camp and to instead structure it similar to college classes.

Joseph said the City should also put recommendations from the City's task force to reimagine the police in place, including ending the use of police dogs and not having officers "self-initiate" calls.

Chacon said he also is committed to leading the rank-and-file through the transition, despite not being their preferred candidate for chief.

"I feel confident that I am going to be able to win the hearts and minds of those who have doubts about me," he said.