AUSTIN, Texas — Over the past year or so, critical race theory (CRT) became a political buzzword across the country and in the Republican-led Texas Legislature.

So, what is CRT?

It's the core idea that racism isn't the result of individual prejudice but also something embedded in legal systems and policies.

CRT isn't taught in Texas public schools, but lawmakers passed two CRT bills earlier this year. Now that the school year is in full swing, the KVUE Defenders checked in with teachers to see how the laws are affecting their classrooms.

While the two laws became synonymous with "critical race theory," neither uses that term. However, both laws focus on how teachers talk about racism, history and current events – and they've created a lot of confusion.

The KVUE Defenders visited several Central Texas schools to see how they're dealing with the new laws.

In Carlen Floyd's ethnic studies class, Bowie High School juniors and seniors in South Austin are using art to study other topics.

"We get a chance to dive into both history and current issues," Floyd said.

For the past 26 years, Floyd has guided her students through different discussions, including House Bill 3979, one of the so-called CRT bills.

"My students can tell you what the bill is," she said.

Floyd said she isn't concerned about how HB 3979 will impact her teaching.

"I think if it brings attention to what matters to students, it's great," she said.

But other Austin ISD teachers, like Kynan Murtagh, are worried.

"My main reaction was frustration," Murtagh said.

Murtagh teaches social studies, among other subjects, at Travis High School in South Austin. He said HB 3979 undermines teachers who are already dealing with so much due to challenges caused by the pandemic.

"And in a context where everything is already, like, so close to the breaking point to be told, like, 'Jump through a bunch of additional hoops to be very, very careful what you're doing. Don't trust yourself about what's important knowledge,' you know, like, that was difficult," Murtagh said.

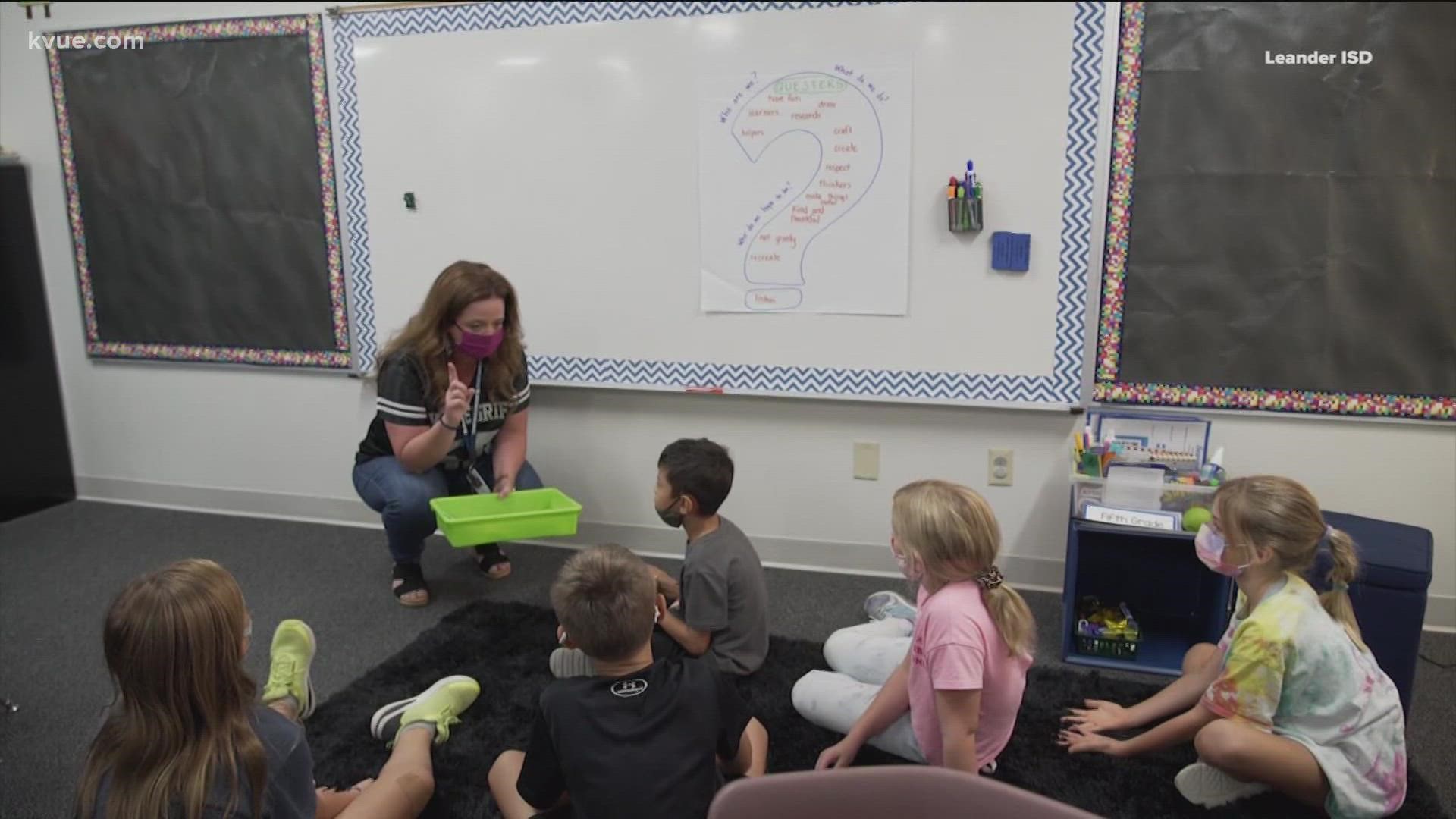

In the Leander Independent School District, spokesperson Corey Ryan said most of the teachers feel the same as a result of the CRT laws.

"Teachers feel attacked and teachers are feeling overwhelmed," Ryan said.

He also pointed out that HB 3979 has had a direct impact on the district's curriculum.

For the 2021-22 school year, third- and fourth-graders taking social studies can't write a persuasive letter to their lawmakers like their classmates before them, because HB 3979 doesn't allow teachers to give class credit for that assignment.

"They didn't get that opportunity in school to write a letter to address something that was really personal to them," Ryan said.

But that will change with a new law recently passed during the third special legislative session.

HB 3979 went into effect on Sept. 1, but on Dec. 2, Senate Bill 3 takes over.

SB 3 continues HB 3979's provision that a teacher "cannot be compelled to discuss a currently controversial issue of public policy." But SB 3 changes the requirement for what a teacher must do if they choose to discuss a controversial topic.

Instead of having to give equal weight to all sides in any controversy as required in HB 3979, SB 3 states "teachers shall explore the topic objectively and in a manner free from political bias."

And, like HB 3979, SB 3 doesn't mention the term "critical race theory."

SB 3 author Sen. Bryan Hughes defended his bill when it passed in the summer.

"Classrooms should be places for fostering a diverse and fact-based discussion of various perspectives. They're not for planting seeds for a divisive political agenda," Hughes said.

The laws have caused teachers to ask a lot of questions.

"When I'm studying Reconstruction, if we're saying that Jim Crow laws are in place because they're promoting white supremacy, am I violating the law?" asked Jessica Jolliffe, director of humanities for Austin ISD.

Jolliffe said what's concerning is the reason behind the questions.

RELATED: Texas This Week: Lawmakers weigh in on bill to stop teaching critical race theory in schools

"I think the danger in the pieces of legislation is it causes enough pause, or it can cause enough pause on the part of teachers, in the part of school districts to ask, 'Should I engage in this perspective-taking? Should I share this particular resource?'" Jolliffe said.

That is not a concern for Cuitlahuac Guerramojarro.

"One way that we fight white supremacy, one way that we're anti-racist educators, is through representation," Guerramojarro said.

He's a teacher at Dessau Middle School in Pflugerville ISD.

Even though he's a STEM teacher, not a history or social studies one, Guerramojarro makes it a point to bring underrepresented and diverse voices into the classroom.

The seventh- and eighth-grade teacher said he doesn't plan to stop, despite the passing of HB 3979 and SB 3.

"And this bill isn't going to stop me from doing that or shy away from why I do it. 'Mr. Guerra, why is it that we learn about women or learn about Black or Brown people in STEM?' And the reason is simply because we want everyone to be represented. And no, no, SB 3 isn't going to stop us from doing that," Guerramojarro said.

The KVUE Defenders reached out to 17 Central Texas school districts and asked how the new laws affected their curriculums.

Pflugerville ISD sent the following statement:

"We are aware of HB 3979/SB 3, and we are working with our curriculum team and administrators to be in compliance and best meet the needs of all students."

In Eanes ISD, where allegations of racism led to the hiring of a diversity, equity and inclusion consultant in 2020, the Defenders wanted to see how the district was handling the CRT bills.

Chief Learning Officer Susan Fambrough is in charge of the district's curriculum.

"It was really a matter of what can we teach, what can we not teach, and it came back to the same thing: we teach our TEKS," Fambrough said.

Teaching TEKS means using the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or the state's current minimum standards for academic achievement, as the driving force of curriculum.

The following school districts are doing the same: Austin ISD, Round Rock ISD, Hays Consolidated ISD, San Marcos Consolidated ISD, Lockhart ISD, Wimberley ISD and Lake Travis ISD.

Del Valle ISD, Dripping Springs ISD, Bastrop ISD and Georgetown ISD did not respond to our request.

And what's in TEKS could soon change thanks to the new laws. They direct the State Board of Education to add civic courses to TEKS.

Ana Ramon is the deputy director of advocacy for the Intercultural Development Research Association, a nonprofit that fights for equity issues in education.

"All of these subsequent bills and sessions was meant to do one thing and that was to attack diversity, equity, inclusion. Attack honest and truthful conversations in the classroom and attacked teachers trying to have those conversations with their students," Ramon said. "In conversations with students and teachers and parents as recently as yesterday, students are already feeling that and being told by their teachers, we can't have these conversations."

But what happens if a teacher decides to teach outside the parameters of the new laws?

Ramon said that's why advocates, teachers and school districts are all waiting on guidance from the Texas Education Agency (TEA) on how to move forward with enforcement. The Defenders reached out to the TEA several times to try to get some answers and have yet to receive a response.

Back in Ms. Floyd's ethnic studies class, underrepresented voices are visibly present. It's now a wait-and-see approach to figure out how the CRT laws will affect the power of those voices.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: