AUSTIN, Texas — Human trafficking victims can often feel punished long after their enslavement.

Texas is behind most states when it comes to helping sex trafficking victims clear their names.

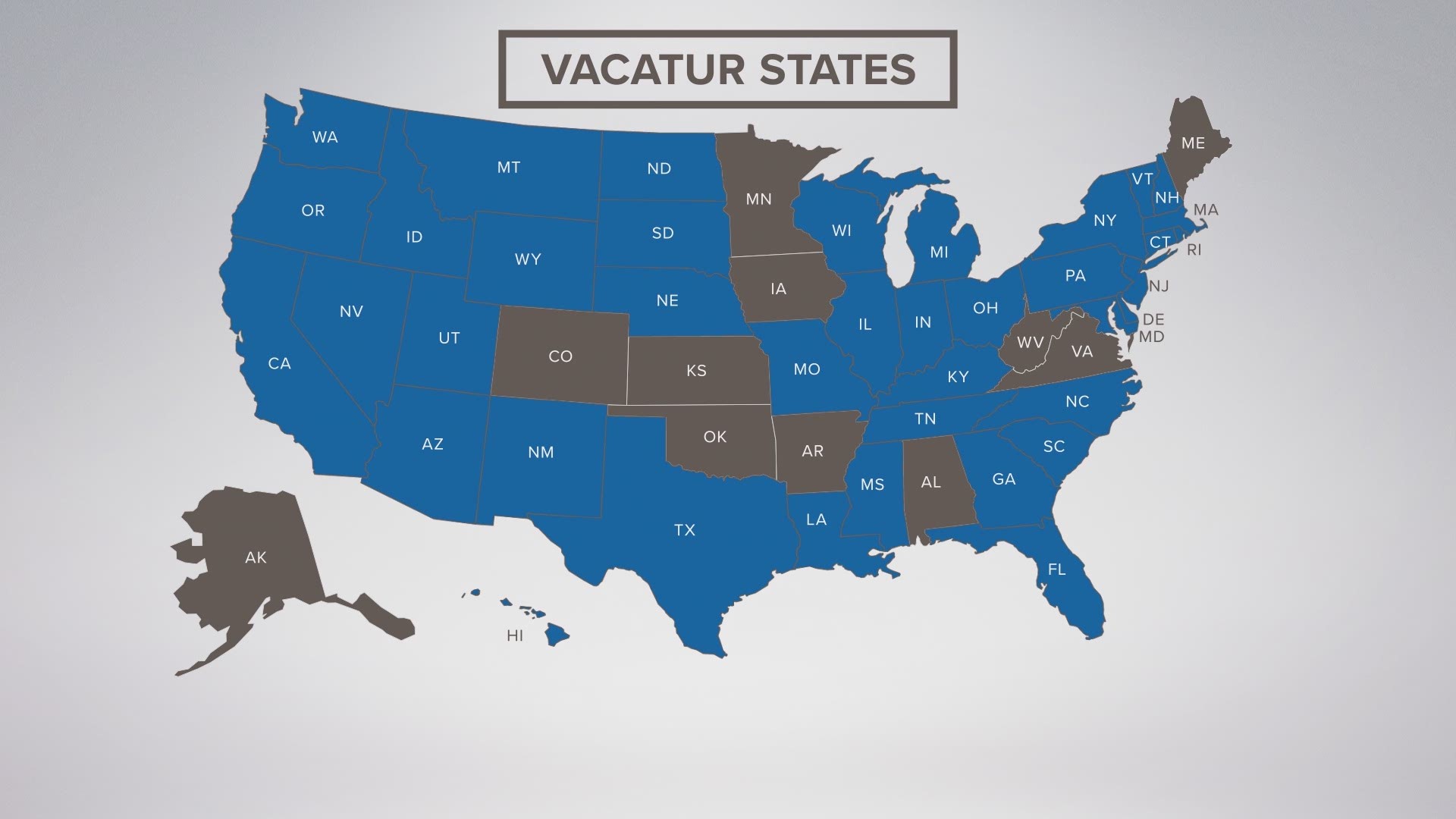

The KVUE Defenders found 30 states allow trafficking victims to get crimes removed from their records if they were forced to commit them under someone else’s control.

Texas doesn't have any such law.

How Allison Franklin got charged with 8 felonies while being trafficked

“Someone else identified me [as a human trafficking victim],” Allison Franklin said. “So many victims do not self-identify. That’s the hard part about all of this. While we are looking around for individuals who are bound up and tied up and beat up, we’re not seeing the individuals that believe that that’s their man or their husband."

Franklin said her path to human trafficking began as a child. She was sexually abused by her grandfather.

“It’s a common thread in almost every single individual that I serve [with counseling],” Franklin said.

Looking for any way out, she became a runaway at 11 years old.

“I was on the streets of Houston at two, three, four in the morning. No clothes, no food. I started to use drugs as a way to mitigate all of the effects of my trauma,” Franklin said.

She said she got the drugs from school. Eventually, she joined a gang and became a dealer to her classmates.

In spite of her drug use and gang life, she graduated and went to college.

“I think sometimes I went to school because it was some normalcy,” Franklin said.

The trauma was there — and building.

“I had gotten clean and tried to get my life back together, but then all of the flashbacks and all of the unresolved trauma would come back, and I only knew to either mutilate myself or get high,” Franklin said. “I was homeless, living in a car, working full-time, going to school, [getting] straight A’s, made the Dean’s List. And getting high.”

In college, she fell in love and moved to California. She stayed sober until her boyfriend died in an accident she witnessed.

“I came back [to Texas], and I had that trauma on top of the trauma that I already had,” Franklin said.

This time, drug use led to prostitution. She worked gang-controlled streets, but she was no longer in a gang.

“Those [other gang members] were saying how much money I was generating, but they weren’t getting any of it. I kept getting kidnapped. And I knew, I knew that every time someone would say, 'Who are you representing?' They were asking who my pimp was,” Franklin said. “I could get raped and robbed twice in the same day.”

She said it was part of recruiting her.

“I can distinctly remember the day I met my trafficker,” Franklin said.

She said a man was beating her with a pistol, and her would-be trafficker stopped the attack.

“He told me, ‘I have higher rank, I can protect you. You’re too beautiful out here, to be out here, you’re too cute. You don’t have to do this,’” Franklin said.

She said the man — whose name is withheld because he has not been charged with human trafficking — took her to his home.

“He loved on me, doctored me and took me shopping the next day. He let me cry on him and started the grooming process,” Franklin said.

“Grooming” is how a trafficker builds trust. Often, a trafficker acts like a boyfriend, promising love and buying gifts.

But it’s only temporary.

“All of a sudden, everything that he had given me, one day I owed him for it,” Franklin said.

Under a trafficker’s control, victims often do more than offer sex: they become a scapegoat.

“They steal guns. They steal cars. There’s laundering money. All those different things that go in with that. [Traffickers] insulate themselves from all of the risks and set up other individuals to take the fall,” Franklin said.

She said she took the fall eight times. She was charged with eight drug felonies.

“He has chained me to a stove. He has had gang members watch me at my grandmother’s funeral so that I wouldn’t leave. He’s poured boiling water on me. He’s hit me with the truck. Those fears are there, but more for me, was the psychological bondage,” Franklin said. “I didn’t look at it as trafficking. 'He loves me. That’s not my pimp, that’s my husband. He loves me.'”

Allison broke the cycle of abuse when she got her last drug charge.

“I took a drug charge for him, April 16, 2011. I got deferred adjudication, which was by a miracle. I got into a specialty court,” Franklin said.

There, someone identified her as a human trafficking victim. She got specialized therapy.

“I’ve been out of the life and have yet to commit a crime. I have yet to go into a mental hospital. I have yet to mutilate myself or use any type of substance abuse or substances since I have had connection with individualized, specialized services. The one time I was connected to that, I’ve never turned back,” Franklin said.

A fresh start doesn't come easy for human trafficking survivors

Punishment, though, goes beyond jailhouse walls.

“When I moved here to take a job, I applied at 30 different places trying to get a place to live. I thought, 'Austin is progressive city.' Well, ‘We’ll take your dog, but we can’t take you,’” Franklin said.

The crimes she said she committed while under someone else’s control still follow her.

The U.S. Department of State said 39 states allow survivors a way to dismiss criminal charges resulting from being trafficked. It’s called “vacatur," and the department defines it as a recognition of “factual innocence.” The charges stay on your record.

Texas has a law, but it’s limited. Many trafficking victims either don’t qualify or it’s too costly.

Thirty states allow certain cases to be completely removed or “expunged” from victims' records.

Texas has no such law.

"It’s a system that talks about sex trafficking, but doesn’t actually help them,” Jamey Caruthers, senior staff attorney for Children at Risk, said.

Children at Risk is a nonpartisan group that pushes for better victim’s rights each legislative session.

“Texas talks a lot about, ‘Look, we feel for the victim. We want to help the victim. We want to restore the victim, make them productive members of society because it wasn’t their fault.’ That’s great to talk like that, but we really need to create a path where that can actually happen,” Caruthers said.

State Representative Senfronia Thompson, District 141, tried to make that happen for at least the last two sessions.

“We passed a bill in my body. It fails in the Senate. As a result of that, we can’t go anywhere,” Rep. Thompson said.

So far this session, no bills leading to expungement are filed. Rep. Thompson, instead, seeks to enhance the “non-disclosure law.” It would keep the crime on a trafficking victim’s record...but sealed.

The Texas Attorney General’s Human Trafficking Division is also working with lawmakers to enhance the non-disclosure law.

“I have had car insurance turned me down or raise my rates because of my record,” Franklin said.

Franklin now helps counsel other survivors and speaks to lawmakers across the nation.

“How do you expect someone to recover if you limit them from any type of economic agency? How can I live a sustainable life? You’re a living individual in shackles,” Franklin said.

On March 1, Representative Tan Parker (R-Flower Mound) filed House Bill 2906 to strengthen the nondisclosure law.

How you can voice your opinion

Changing the way we treat survivors starts in the legislature.

A non-disclosure bill is filed. Click here to read about it.

If you have a story idea for the Defenders, email defenders@kvue.com.

Follow Erica Proffer on Twitter @ericaproffer, Facebook @ericaprofferjournalist, and Instagram @ericaproffer.