Migrant child spent 10 months in detention center before he was paired with a sponsor family

The Sewell family wanted to become sponsors for Byron, a Guatemalan child who was separated from his family. But the process proved to be anything but easy.

A Central Texas family wanted to help ease the burden of separated children at the border.

When they asked to become sponsors for a child, they met unexpected hardships.

Their story is part of an in-depth look at sponsorship, detaining migrant children and securing the border.

The Fight for Byron The Sewell family wanted to do more for a migrant child than just donate money

Thousands of migrant children are held in detention each year, separated from their families. For some, their parents crossed illegally and got deported.

There's never any guarantee they’ll be reunited.

“There’s so many children that were separated, somewhere around May of last year. My husband and I talked about just us being in that position, if ever we had to escape violence or persecution and needed to take our kids and go somewhere for sanctuary or asylum,” Holly Sewell said.

Instead of giving money to an organization, Sewell wanted to do something bigger.

“What can we actually do to help the situation?…What we would want to have happen to our children?” Sewell asked. “We would want a safe family to take them in and treat them like one of their own.”

So, that's what she tried to do. After reaching out to several nonprofits, a friend connected her with attorney Ricardo de Anda.

Sewell said she could take in a child, but not a teenager since her children were five and eight years old.

“There was no mechanism in place at all for us to help in that way,” Sewell said.

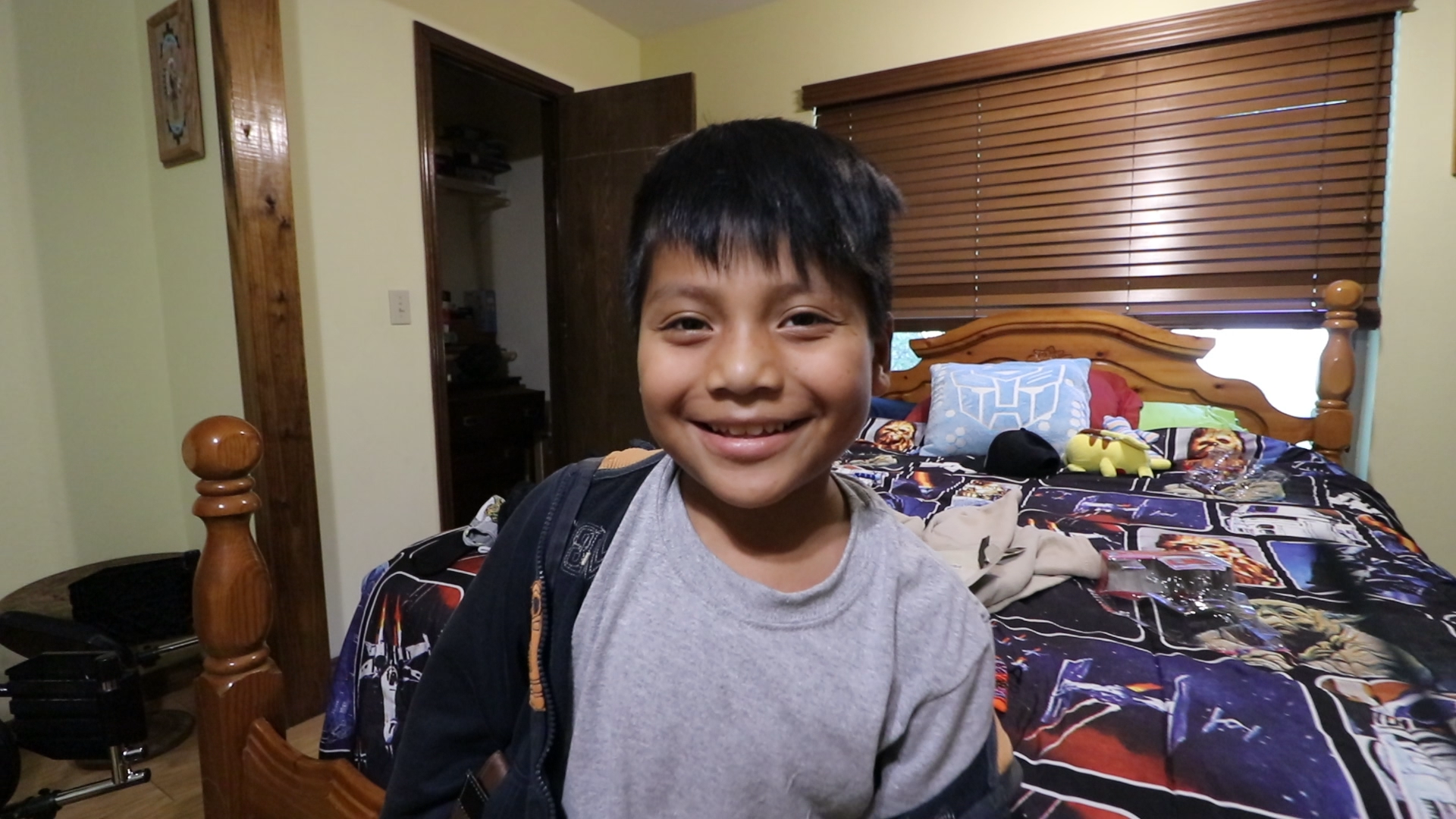

De Anda told Sewell about Byron, a detained 8-year-old boy from Guatemala whose father was deported.

Before Sewell would agree to sponsor Byron, she wanted to speak with his family.

David Xol-Cholom, Byron’s father, fled Guatemala after gangs beat him for his evangelical Christian beliefs. They threatened Byron. So, Xol-Cholom crossed the U.S. border illegally and faced illegal entry charges in McAllen, Texas.

Before the judge, Xol-Cholom asked about his son.

“I wish for him to be returned to me,” Xol-Cholom said.

Byron wasn’t returned.

“It was the beginning of October when [ORR] denied us,” Sewell said.

The Office of Refugee Resettlement or ORR oversees separated children.

“The only thing they said was that we did not have a prior relationship with him before he migrated,” Sewell said.

Their policy shows a sponsor must be a relative or have a prior relationship with a separated child, neither of which fit the Sewell family.

Bryon could be placed in foster care, but the Sewell family isn't a licensed foster family.

“All we wanted was to be vetted,” Sewell said.

De Anda sued ORR, claiming the government agency violated prior court agreements and didn’t give Byron due process, among other violations.

“The interest at issue here is this child’s freedom,” De Anda said. “It is legal to ask for asylum. He is here legally.”

ORR supervisors said the policy is for child safety, to prevent abuse and human trafficking.

“Certainly, the right of the parents to choose what’s in his child’s best interest is a paramount right. That’s why we’re before this court – only because the parents chose Holly Sewell and her family,” De Anda said.

The court ordered ORR to consider the Sewell family. It took a little more than two weeks for the government agency to approve the sponsorship.

“Oh, my goodness! So excited,” said Sewell as she greeted Byron at the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport.

Byron spent 10 months in detention. His family said he had a birthday with no celebration.

Also, Byron’s leg was broken while playing soccer in detention. Nurses wrapped his ankle. Three days passed before a doctor realized Byron had broken his femur.

Within minutes after his arrival, De Anda connected Byron with his family in Guatemala.

When they arrived at the Sewell house, Bryon saw his own room. A giant sign reading “Bienvenidos Byron” was placed above the bed, welcoming him to the temporary home.

Photos from his family from a video call were taped to his closet door. Sewell’s children posted drawings representing love.

De Anda doesn’t get paid to represent Byron. He said he also has other clients in similar situations.

“I’m doing this because it’s the right thing to do,” De Anda said. “Byron’s case is going to open the floodgates.”

Xol-Cholom, while in Guatemala, has a pending asylum case in the U.S.

“Now with Holly’s family, we’re sure he’s going to have good health and have those feelings of being a child like he used to," Xol-Cholom said. "We’re asking God to help us with Byron’s absence, for our health and all of that."

If Xol-Cholom’s asylum case is granted, he will be united with Byron.

If denied, Byron’s case will be reviewed separately.

Moving forward How to best care for migrant children

Like Byron before his sponsorship, there are thousands of unaccompanied children who remain in government custody across the country.

While each child’s future is decided separately in court, Byron’s attorney Ricardo De Anda hopes his case may open the door to similar court rulings in the future.

That is after all, what the law demands. In 2008, Congress ordered the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) – the parent agency to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) – to promptly place a minor in “the least restrictive setting that’s in the best interest of the child.”

The least restrictive setting, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), is an actual home with an actual family, given it’s deemed safe.

“In the case of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, you have children who don’t have a buffering adult that they know and love with them,” said AAP Immigrant Health Special Interest Group Co-Chair Julie Linton. “Although those conditions are more child-friendly, we would argue that children would be best served in the community where they are in the care of a sponsor who loves them.”

Dr. Linton argues the longer a child spends away from a loving adult, the more detrimental to his or her development.

“‘Toxic stress’ is serious, prolonged stress in the absence of the buffering support of a parent or guardian or some other stable adult figure,” she said.

This increases the likelihood of developing chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder, Dr. Linton added.

As the number of unaccompanied migrant children crossing the border continues to rise, the longer it takes for ORR to find suitable sponsors.

The average time to place a child with a sponsor has gone from 60 days in 2018 to 66 in 2019, according to a recent agency’s fact sheet.

The report also stated 32,000 minors have been referred to HHS between October and March.

That’s about a 50% jump compared to 2018 when the zero-tolerance policy and the migrant family separations took place.

There are approximately 13,000 migrant children currently under ORR care.

Focus on the government’s ability to care for children has intensified after the death of four Guatemalans in the last six months. The third case involved a teen who had crossed the border without his parents.

In Byron’s case, it took staff three days before they realized he had broken his leg while being held in one of 168 HHS network of shelters.

“It becomes incredibly difficult to be able to handle the numbers that are coming in a way that is compassionate,” Dr. Linton said.

Advocates argue opening the sponsorship program to other willing families who are not relatives – which was at the center of Byron’s lawsuit – may allow for quicker placement.

“There’s literally thousands and thousands of children that are in detention because they have no relatives in the US that would take them in,” De Anda said.

While the state district judge who ruled on Byron’s case isn’t setting a precedent, De Anda hopes it will allow for other unaccompanied migrant teens in the U.S. to be sponsored before they turn 18 years old and get deported.

“We have 15, 16, 17-year-olds that are in detention and their parents want them to stay in the US because it’s a better life for them,” De Anda said. “And they have a right to be in the U.S. but they can’t find any sponsors because they have no relatives in the U.S.”

The government argues that the policy of limiting sponsorships to familial relationships is for the protection of the child.

“It's meant to encourage genuine sponsorships and mitigate the risk of releasing unaccompanied minors to human trafficking,” U.S. Attorney for the Southern District Of Texas Paxton Warner told US District Judge Fernando Rodriguez during a March 25 hearing in Brownsville.

Whether Byron’s case will provoke a change in ORR policy is yet to be seen.

Both De Anda and Dr. Linton believe each migrant child deserves legal representation to have a shot at a life in the US.

According to the Executive Office for Immigration Review, 35% of all unaccompanied migrant children represent themselves in court.

Faux families crossing the border Fake family units are a serious problem, according to homeland security investigators

The stories aren't always like Byron and his dad, David.

In April, homeland security investigators spoke with about 100 families. In a news release to KVUE, HSI said fraud was in more than a quarter of the cases.

The fraud includes forged birth certificates or other documents to claim parentage. Some adults also use fake documents to claim they’re a minor.

On April 22, two people were discovered to be 23-year-old men posing as minors. They will be prosecuted for visa fraud and making false statements.

"What we're encountering now with particularly some of these family units is sort-of a looser conglomeration of entities that know each other but don't necessarily work hand-in-hand,” said Shane Folden, HSI Special Agent in Charge, San Antonio.

Homeland Security called in more analysts and specialists to the Texas border because smugglers were using these "fake family units" to get through.

Families with minors are housed differently. They're processed differently. Because of prior court rulings, families often get released while their immigration case works through the courts.

Homeland security investigators say faux families are big business.

"We've also encountered children who are provided to strangers, just for the purpose of coming across as a family unit – a fraudulent family unit," Folden said.

Folden said parents get paid and/or are threatened to give up their child to a smuggler.

The extra investigators went across the Southwest border. In Texas, the extra staff serves in El Paso and Harlingen. They are made up of criminal and document analysts, forensic interview specialists and victim assistance specialists.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) also sent 330 extra deportation officers to the border.

HSI encourages the public to report any suspicious activity through its toll-free tip line at 1-866-DHS-2-ICE or by completing its online tip form.

If you have a tip for the KVUE Defenders to investigate, send an email to defenders@kvue.com or call 512-533-2231.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: