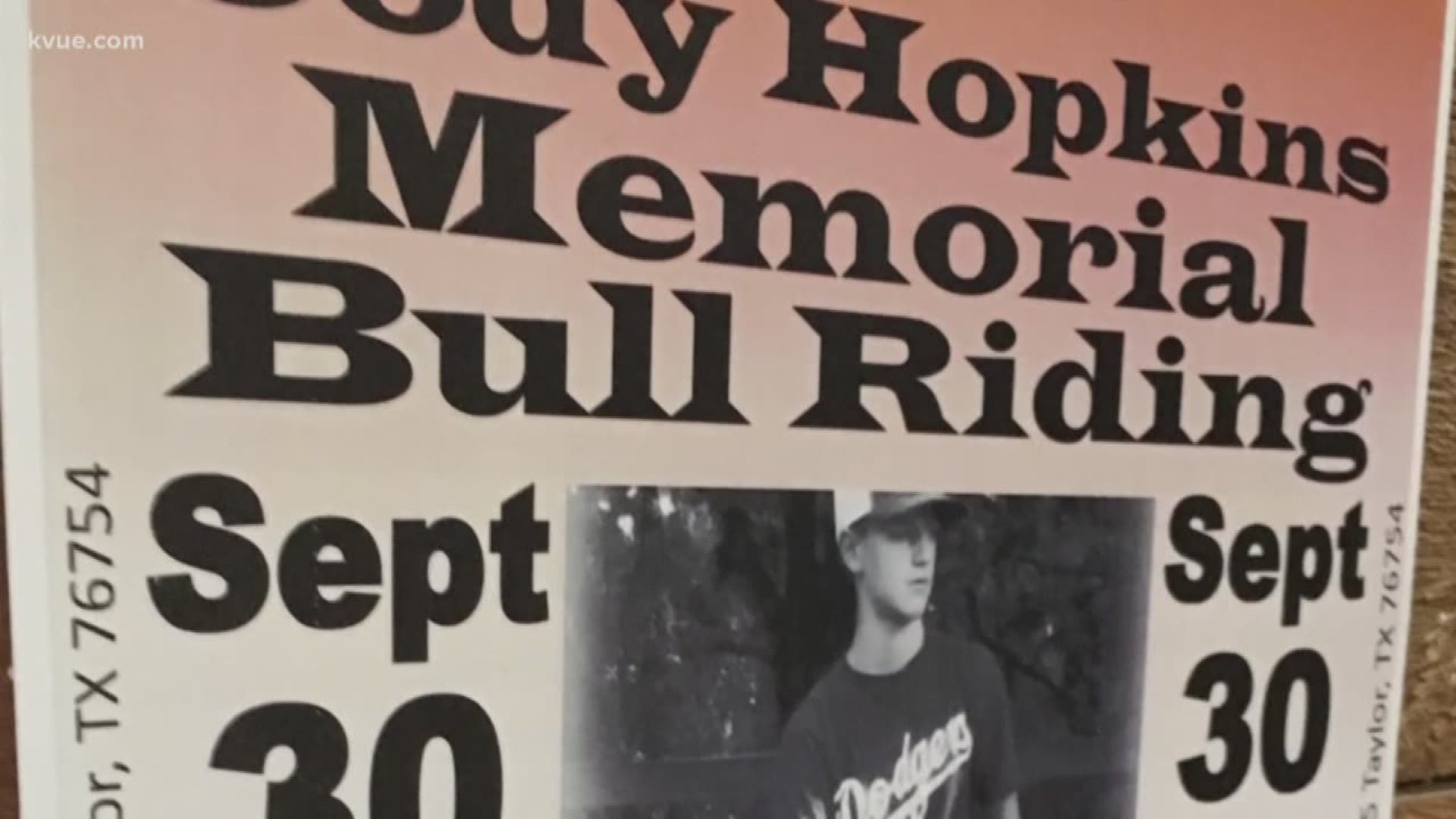

In nearly two years since Cody Hopkin’s death, his family has hosted two memorial bull-ridings, raised thousands of dollars for research and done countless hours of research into the West Nile virus.

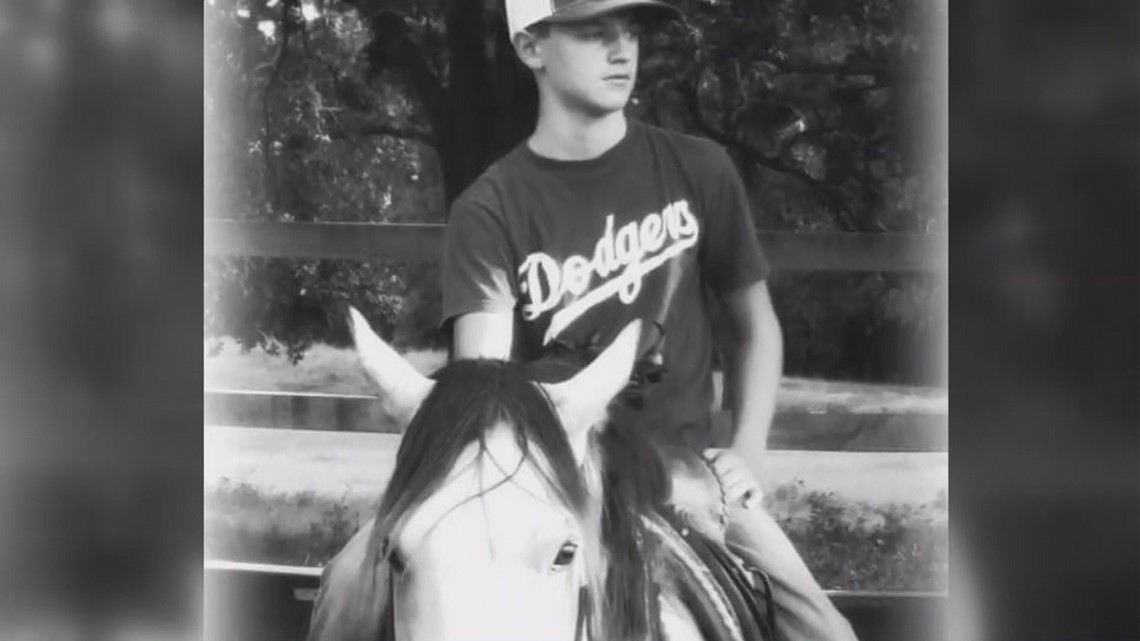

Hopkins, an avid bull-rider and rodeo fan, was just 13 years old when a mosquito bit him and injected him with the virus. The virus passed into Cody’s brain, causing West Nile Encephalitis and killing him.

“I don’t want another parent, grandparent, aunt, uncle, brother or sister to feel the pain that we have gone through,” Rosalee Hopkins, Cody’s grandmother, said.

Rosalee spent so much time researching after Cody’s death that she was invited to speak at a meeting of the Texas Health and Human Services Task Force on Infectious Diseases.

The late boy's grandmother told the board members his story and how they felt West Nile needed more attention.

Then, Rosalee heard the voice of Dr. Kristy Murray.

“It’s been heartbreaking to see what families go through,” Dr. Murray said on a conference call at the meeting.

Dr. Murray explained how she’d been researching West Nile since 1999 and was also frustrated by the lack of attention the virus received.

Dr. Murray has spent nearly two decades researching the virus. She was on the CDC team which first discovered West Nile in the United States and has accumulated a larger resume since then -- serving as a Professor of Pediatric Tropical Medicine, the Assistant Dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine and the Associate Vice Chair of Research for the Department of Pediatrics at both Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Murray invited Rosalee and the rest of Cody’s family to her lab in Houston. What she had to say enraged the family.

"There are several vaccines, not just one, that have already made it through the clinical trials,” Dr. Murray said. “There are actually several vaccines that have made it through phase one and phase two of clinical trials.”

The records show at least nine vaccine trials, some dating back more than a decade. Many of those trials had “completed" phases.

“As a parent of a child who died from West Nile, that makes me extremely angry,” Greg Lashmet, Cody’s father, said.

Dr. Murray said she shares the family's frustration.

"It's really upsetting to see the long term impact this virus has on people's lives and knowing that there is a vaccine out there that works and could prevent it,” Murray said.

Research for the West Nile virus did once have plenty of funding, according to Dr. Murray. When the virus first started spreading across the country, medical research companies and government agencies supplied plenty of money to figure out what the virus was.

Almost 20 years later, however, the research resources have subsided.

“It just doesn’t get the attention that it needs still and it’s really upsetting to see,” Dr. Murray said.

There are multiple parts to the funding problem. First, the low number of cases has affected the lack of research.

Then, there's the idea of who the virus effects. It's been typically shared as a virus that's most dangerous to the elderly, especially those with previous conditions.

If the virus is only hurting a small population of a small target group, then why would pharmaceutical companies fund the final stages of research?

Well, Dr. Murray argues the numbers are wrong.

“We are definitely not testing enough,” Murray said. “Only 30 percent who come in with clinical signs of disease are actually getting tested.”

Just like Cody's case, even with reported West Nile in the area, human tests aren't required or even thought of often. This means many cases and lots of research may never be known about.

Dr. Murray and her team have researched the virus non-stop and she said they also believe it can be dangerous to a much larger part of the population than previously thought. The virus has also shown to cause neurological and physical damage, which can last in patients for years after treatment.

"This is something that is continuously happening year after year and it's going to keep doing that until we have a way to protect ourselves,” Dr. Murray said.

Dr. Murray believes this is why the work Cody's family is doing is important.

"You lose a child and there's a lot of things that you think you couldn't do that you start doing,” Greg Lashmet said.

After learning their life changing loss could have been prevented, Cody’s family are even more determined to get the vaccine out.

"We can't change everything,” Lashmet said. “There's still gonna be a lot of nasty dirty things... this is one thing we can change. There's a vaccine sitting in a refrigerator. It's waiting to go."

Like their 13-year-old facing down a 2,000 pound bull, Cody's family and the community are taking on a monumental task: to convince the medical community and pharmaceutical companies that the West Nile virus research deserves funding.

“Cody's favorite song was 'One man can change the world,’” Rosalee said. “He's not here to do that, but we are. We can do that for him.”

With the help of Dr. Murray and other officials and families across the country, they're already taking steps.

Rosalee will speak again with the state soon at a special meeting for West Nile only and she’s set up meetings with other West Nile families and officials to follow.