Mysterious case of Michelle Vanek: 18 years after she vanished, a clue to her disappearance is found

Vanek and her hiking partner split up on Mount of the Holy Cross, and she was never seen again. A newly discovered clue might explain what happened on that fall day.

Chapter 1 An 18-year mystery

After 18 years of wondering – of questions whose answers remained frustratingly out of reach – a weather-beaten hiking boot tucked against a boulder in the wilderness south of Vail might finally have solved the mystery of a woman who vanished without a trace.

The woman’s name was Michelle Vanek. She was 35, a wife and mother of four. On Sept. 24, 2005, she and a family friend attempted to summit her first 14er, the rugged and unforgiving Mount of the Holy Cross.

They separated near the summit, and nobody ever saw her again.

The largest search in state history, carried out over eight days by more than 800 volunteers on foot and in the air, failed to unearth a single clue of what happened to her.

Not a footprint.

Not a scrap of clothing.

Not a hiking pole or a piece of her backpack or the wrapper of her last energy bar.

In that void, there was only speculation and suspicion.

Then came the discovery of the boot – the first clue ever discovered to what happened on that brisk fall day.

The Sorrel Asystec with a black rubber sole, its leather upper shredded by the time and the elements, might have laid propped up on that boulder until the sun, wind and the unforgiving freeze-and-thaw cycle at 11,700 feet returned what was left of it to the earth.

Instead, a father and son, hiking in an area where almost no one ventures north of the summit of Mount of the Holy Cross, came upon it, recognized it might be important, snapped some photos and alerted authorities. It took two trips for searchers to find it again, and it took forensic work to determine that it was, indeed, Vanek's left boot, purchased the day before the hike.

“It changes the narrative,” said Scott Beebe, president of the board of Vail Mountain Rescue Group .

He said it gives him confidence that he now knows what happened was a tragic accident and not the result of something untoward.

It tells him the assumption made during the original search – that Vanek, out of food and water and possibly suffering from altitude sickness, likely headed west after getting lost – was wrong.

And it tells him something else: That on that day, 18 years ago, the difference between life and death was 10 minutes in time and 100 feet in distance.

Chapter 2 The wrong trail

Vanek and her husband, Ben, had known her hiking partner and his wife for about a decade. They had socialized as couples a handful of times each year, sometimes going out to dinner as a foursome. Ben Vanek and the other man went to a Rockies game together in September 2005, according to the Eagle County Sheriff’s Office’s report on the incident, obtained by 9NEWS.

That was around the time Michelle Vanek and the other man were finalizing plans to finally tackle a 14er – something they’d been discussing for more than a year. She was a marathoner and worked out almost daily but had never climbed one of Colorado’s signature peaks. He had climbed 38 of the state’s 58 mountains reaching at least 14,000 feet above sea level.

After considering other possibilities, the man suggested Mount of the Holy Cross, elevation 14,007.

Hikers hoping to reach the summit of the mountain, where snow-filled cracks form a cross, have two choices. They can take the Half Moon Trail, which is the standard route known as the Northeast Ridge. Or they can take the Fall Creek Trail heading straight south, then climb up the Notch Mountain Trail, which starts near treeline and cuts back-and-forth on the way to a stone shelter at 13,224 feet. From there, climbers follow a looping route around the south side of the mountain – climbing over three 13ers in the process – before reaching the summit.

It's known as the Halo Route.

“The Halo Route is a lot more difficult,” said Beebe, who has climbed Mount of the Holy Cross more than a dozen times. “It's not an easy mountain. It is a long hike … and it's a lot of elevation gain and loss and then regained, and by the end of the day, by the time you come out, you're tired.”

Both routes begin at trailheads in the Half Moon Campground.

Around 6:30 that Saturday morning, after Vanek and her hiking partner pulled into the campground parking lot in her silver Toyota Sequioa, there was confusion. Vanek’s hiking partner later told investigators that they walked around the parking lot but could find only one trailhead, according to the incident report.

“At the time, the Forest Service was putting in a new set of port-a-potties,” Beebe said. “And so there was a lot of construction going on. And there were some piles of dirt that were in front of the trailhead that goes up the Northeast Ridge.”

By then, Vanek was complaining of a headache – a possible sign of altitude sickness. She had some Excedrin, according to the report, and they headed out on the only trail they could find. It was the trail leading to the Halo Route.

When they reached the cutoff to the Notch Mountain Trail, the man had Vanek pull out a map. That’s when they realized then they were on the wrong trail, but they decided they didn’t have time to turn around and still make the summit.

They pushed on, climbing the switchbacks up the slope until they reached a small stone hut built in the 1930s.

A frigid wind ripped across the rocky terrain, and they spent about 10 or 15 minutes in the shelter, warming.

Then they got moving again, skirting a high ridge as they edged closer to the summit. The wind died down, and they could look to the north and see climbers coming up the standard route – the one they had planned to take.

Chapter 3 Vanished

At that point, they had been on the trail for more than 4½ hours, and the man began to worry that they were going to be much later getting home than they had planned. Vanek was falling 30 to 60 feet behind him.

On the final stretch to the summit – maybe as few as 400 yards from the top – Vanek, exhausted and possibly sick from the altitude, said she was out of water and could not go any higher. According to the incident report, the man told investigators that he offered to take her pack – she said no – and then suggested they turn around.

“No,” she said, according to the report, “you go to the summit.”

The man pointed across a boulder field and told her to head that way, toward the trail down, and he would go quickly to the top and catch up with her. She had a couple of energy bars left. He gave her a vanilla bean-flavored tube of energy gel and headed up.

The man reached the summit at 1:42 p.m., called his wife and said they were going to be late because they had gotten onto the wrong trail, snapped a picture of another couple who had reached the top, and headed down.

Growing alarmed when he didn’t see her on the trail down the Northeast Ridge, the man dropped his pack and headed back up. Other hikers heard him calling Vanek's name.

He asked everyone he encountered on the trail if they had seen her. No one had. He found cellphone service and called 911.

By early evening, the first searchers had headed into the wilderness.

Over the next week, when nighttime temperatures fell into the low 20s and a foot or more of snow fell, searchers hunted for something – anything – to give them hope that Vanek was still alive.

After a final, desperate day when 336 volunteers came out to help, and without a single indication as to what happened to Vanek, Eagle County Sheriff Joe Hoy called off the search.

“Michelle now walks with god,” Bob Davis, a family friend, told reporters who gathered for the announcement.

By then, sheriff’s office investigators had interrogated Vanek's hiking partner.

How could you take a novice up that mountain without more survival gear?

Were you involved in her disappearance?

Did you harm her?

The man ultimately said he would not answer anymore questions without an attorney present.

They also questioned Ben Vanek. Was there something going on romantically between his wife and her hiking partner? (“There is nothing.”)

Could the hiking partner have harmed her? (“Doesn’t have a malicious bone in his body.”)

Did he have anything to do with his wife’s disappearance? (“Hell no!”)

With no solid evidence that a crime occurred, Eagle County sheriff’s investigators eventually closed the case.

Chapter 4 The boot

“Ever since I've been on the team,” Scott Beebe said, “whenever we've had a mission on Mount of the Holy Cross, we're reminded, hey, keep your eyes peeled, you know, she was wearing black spandex pants, blue windbreaker jacket. And if you're up there, just keep your eyes open. This mission has never gone away.”

Beebe, who took an interest in Vanek's disappearance when it happened, joined Vail Mountain Rescue in 2010.

“I still have, you know, original newspaper articles about it,” he said. “It’s never been far from my mind. How could somebody just disappear into thin air?”

For so many years, there was nothing solid to help unravel the mystery.

In 2009, a climber found a bone on rocks not far from the Halo Route. It turned out to be a deer’s jawbone.

In 2016, an investigator asked Ben Vanek to provide his wife's dental records for inclusion in a national database of missing persons.

In 2019, Ben and Michelle’s four children provided DNA samples so that if her remains were ever found, they could be identified.

Despite all that, there was nothing solid until a man and his son bushwacked into an area north of the summit of Mount of the Holy Cross, below a rocky slope known as the Angelica Couloir, and came upon that boot. That was in late August 2022.

The boot had obviously been there a long time. It was surrounded by grass, but none was growing beneath it. The leather upper was almost completely gone, ravaged by the elements or maybe animals. The sole was intact, and the man reported the discovery Vail Mountain Rescue.

“We have a clue,” Beebe said. “I mean, it's the first clue in 18 years.”

Later that fall, searchers headed into the Holy Cross Wilderness to try to find the boot. They had no luck the first time. Then the man and his son agreed to lead three searchers, including Beebe, back up the mountain and show them the spot.

It was right where they had first found it.

After photographing the area, and bagging the boot, searchers quickly searched the area, hoping to find something more. They found nothing before heading down the mountain with the boot, which they turned over to the Eagle County Sheriff’s Office.

Then they waited.

Investigators undertook forensic work that led to the inescapable conclusion that the boot was Vanek's.

Chapter 5 Nobody goes there

Once Beebe got the news, planning began for another trip to the area with a more thorough search, but they had to wait for last winter’s snow to melt.

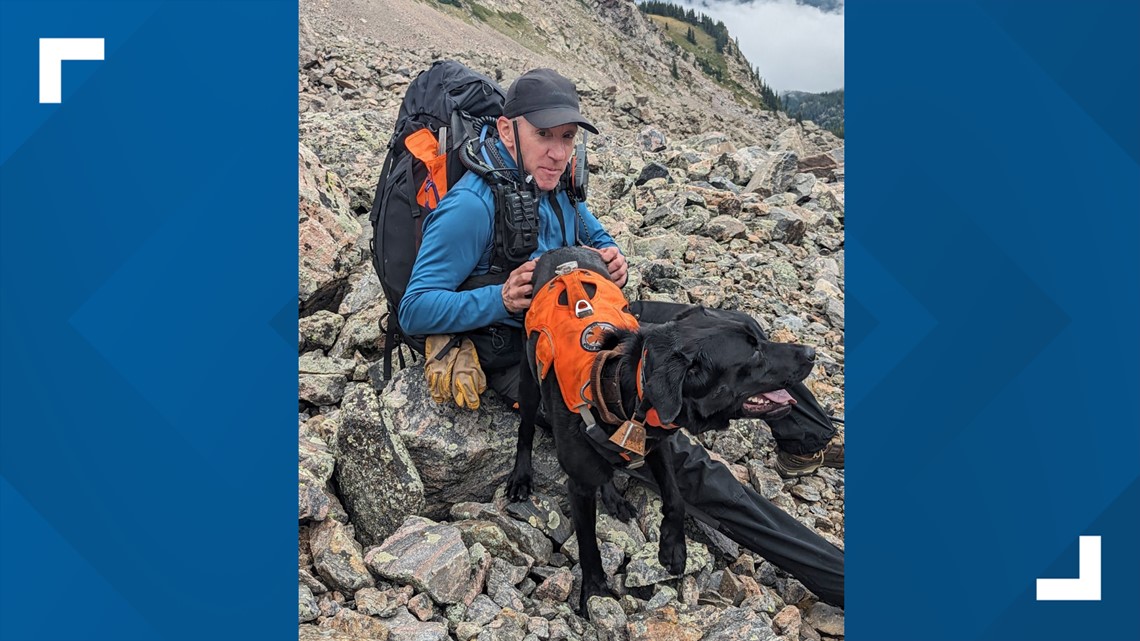

The day finally came on Aug. 25. The San Miguel County Sheriff’s Office sent a helicopter. Other counties sent their cadaver dogs and handlers.

“Weather wasn’t perfect that day,” said Ted Katauskas, leader of Vail Mountain Rescue’s canine team.

He set out with his dog, Stryker. The skies meant a short window for the helicopter to operate.

“We had two hours to … do a hasty search around that area,” he said. “So we ran the dogs all through this campsite and then up Angelica Couloir.”

They had hopes going in.

“Something as small as a tooth,” Beebe said of what they hoped to find.

Again, they found nothing.

“You hope that – especially after 20 years – we're going to find something,” Katsauskas said. “But unfortunately, it's just the way it works with recovery operations. Nature's very good at kind of taking us back to the earth. And it is amazing how quickly that happens in the environment.

“You just disappear,” Katsauskas said.

Even so, Beebe said he's confident now that he knows what happened.

“For 18 years, the narrative been has been, she got lost in the western boulder field,” he said.

That’s the area where almost all those who lose their way near the summit end up. And it’s the area where searchers concentrated their efforts in 2005.

“And now,” he said, “she did exactly what her hiking partner told her to do.”

Instead of heading west, he’s now certain she went north – toward the route that she and her hiking partner had intended to take up the mountain.

Beebe said he believes, however, that she mistook “runnels” – trail-like paths down the mountainside carved by rockfall and snowmelt – for the standard route.

“What she didn't know, she was on the wrong trail and went down into an area that nobody expected her to go – nobody,” Beebe said. “Nobody intentionally goes down the Angelica Couloir."

Beebe said the established trail was about 100 feet to her left. After studying the timeline, he believes her hiking partner missed connecting with her by about 10 minutes.

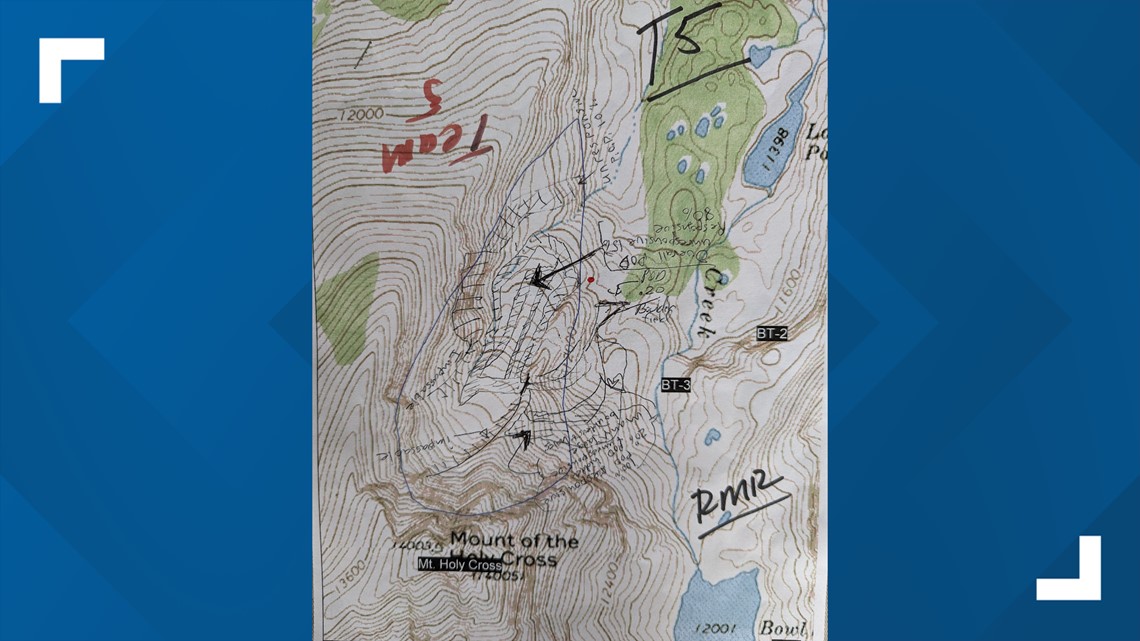

And as Beebe studied the maps marked by searchers in 2005, he noted that the area where the boot was found wasn’t searched until the eighth – and final – day.

“By then,” he said, “there was a foot-and-a-half, 2 feet of snow – and so everything was covered.”

On the map of the area where the boot was found, searchers wrote “impassable” in several places – a notation to the amount of snow there when they tried searching.

Beebe recently met with Vanek's family. One of her daughters asked him what he thinks happened to her mom.

“She wasn't dressed for the weather,” he told her. “I mean, spandex pants, windbreaker jacket. Out of food. Out of water. Having some altitude sickness. No means of being able to start a fire. I said, we know that the temperature that night got down into the low 20s up on the mountain. And I said I think she laid down, and she went to sleep. She didn't wake back up.”

As Beebe talked about the meeting with the family, emotions tugged at him – at the reality that a little time and a little distance made a tragic difference that day.

“It was just,” he said, pausing to gather himself, “an accident.”

Chapter 6 'Wish they had stuck together'

“I don't believe there's any kind of foul play involved,” Beebe said. “I think this is a matter of, you know, made a mistake. Never been on the mountain before. Should they have split up? No, of course not. But we've all done it. You know, if you talk to my wife, we've hiked all the 14ers there are. Four different times, I have got the fever, and, you know, my wife was having trouble keeping up.”

Each time, he told her the same thing.

“Honey, I'm gonna go and tag the summit and I'll come back and meet you,” he said. “And, you know, we got away with it. But this is one of those times … when I wish they had stuck together.”

Beebe would like to share that story with Vanek's hiking partner. He said he believes it might ease the burden he has carried.

So far, he’s been unable to reach him. A message left for him by a 9NEWS reporter has not been returned.

Ben Vanek declined to be interviewed for this story but said he wanted people to know that his family is OK – that “we are living the life we set out to have with Michelle.”

More 9NEWS stories by Kevin Vaughan:

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS