'I still want to know why' | One year later, how the Austin bomber was stopped

Police have shared the fullest account so far about an investigation that was equal parts old-fashioned police work and high-tech surveillance.

One year after the Austin bombings, investigators are opening up about how they retraced the bomber's steps to find him in a joint project by KVUE and Austin American-Statesman. "Stopping the Austin Bomber" will air March 8 at 7 p.m.

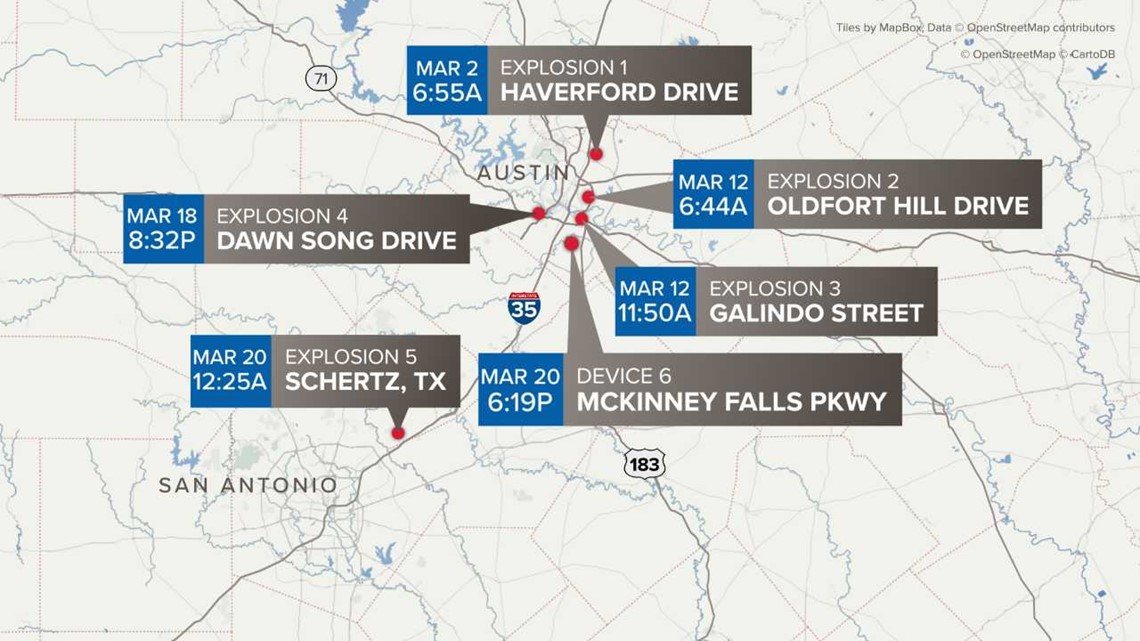

The bombings begin ‘It was a terror that held over a long period’

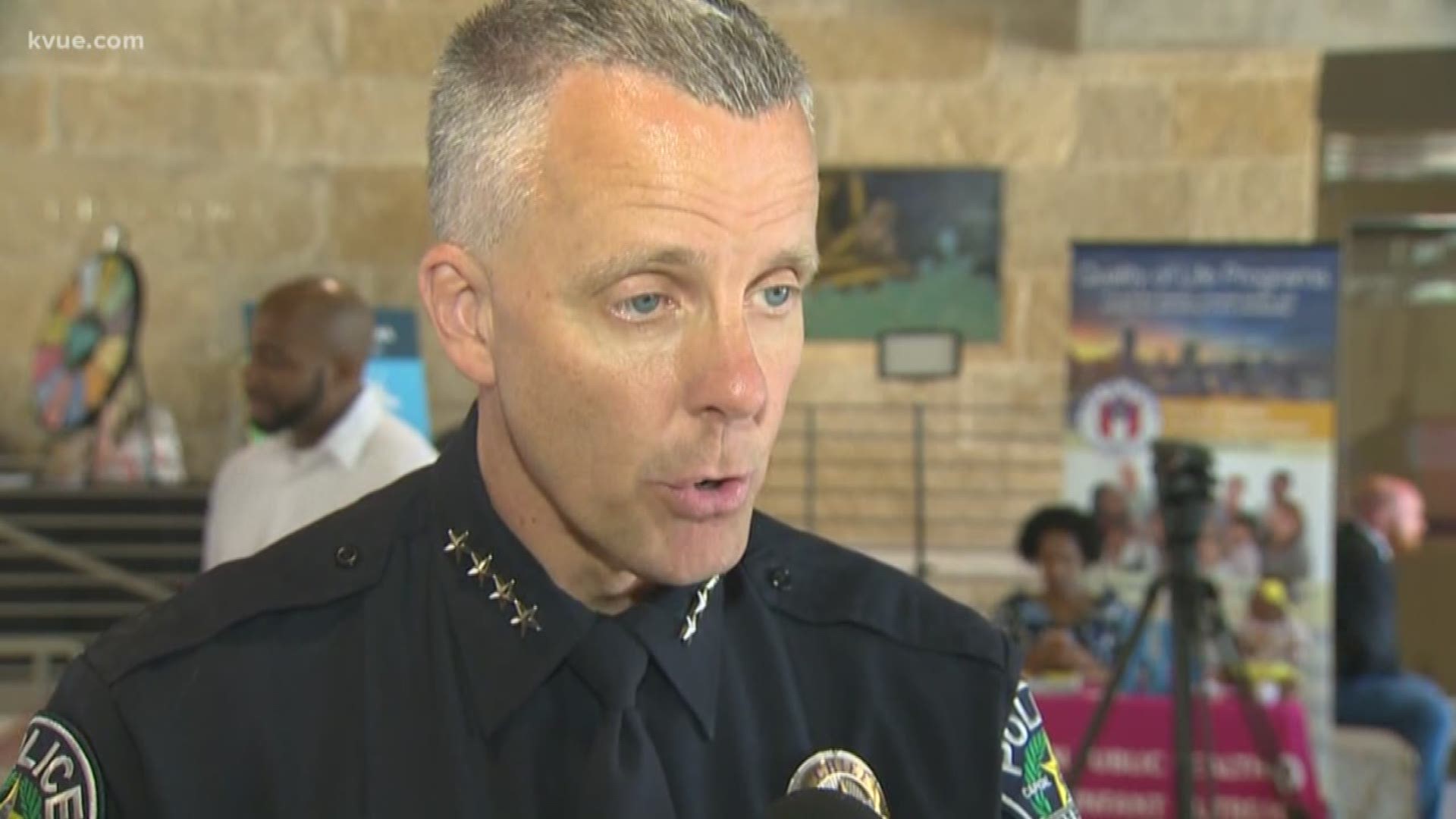

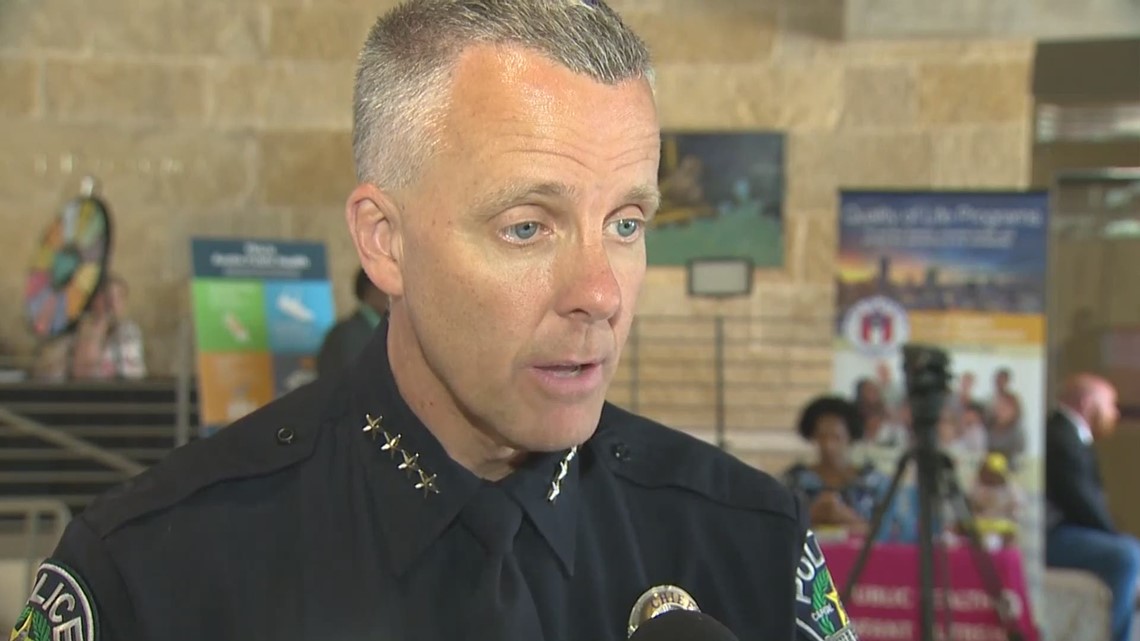

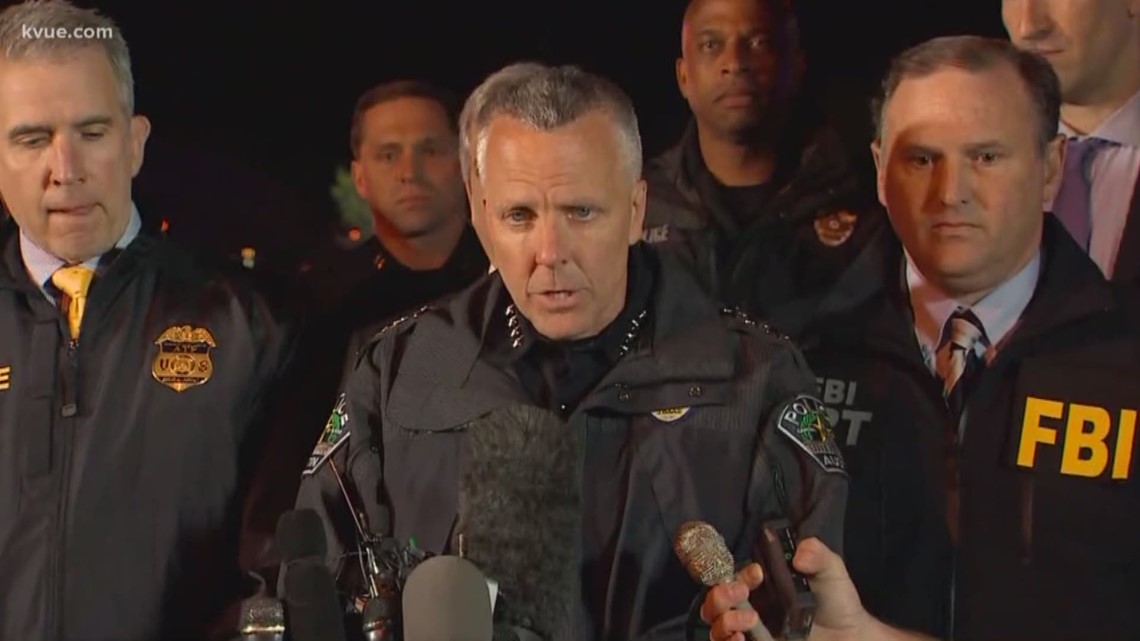

Austin Police Chief Brian Manley was clearing the early morning wave of administrative emails when his cell phone buzzed on March 2, 2018.

Dispatch had just sent officers to a house in northeast Austin on a possible fatality call: A 39-year-old father of one had just been found outside his front door with injuries that appeared to have come from an explosion.

The initial radio chatter from the first patrol officers on the scene was sketchy. Chief Manley, a former Austin homicide detective before rising through the ranks of the Austin police administration, mulled for a moment. Some kind of freak early morning accident? A blown water heater? Someone welding too close to a gas tank?

He asked the watch commander to keep him posted and turned back to his computer.

Across town, Detective Rolando Ramirez was wrapping up errands on what was supposed to be his day off. But, as the new guy on the homicide squad, he was due to catch the city’s next murder case.

Det. Ramirez had learned not to prejudge anything in his previous assignment as a child abuse unit investigator. But what his boss had just told him -- a deadly explosion rocking a subdivision lined with 1980s-era starter homes just before 7 a.m. -- sounded strange.

In the 20 minutes it took Det. Ramirez to reach the red-brick house midway down Haverford Drive, a crime scene team had strung yellow police tape across the wide driveway, the brick-arched entryway and the manicured yard.

Even from the curb, Det. Ramirez could see pockmarks dotting the home’s front door. The first officers at the scene recounted how the dead man’s bloodied chest was so damaged that the neighbor who heard the blast and rushed to help couldn’t figure out where to start CPR.

Though this didn’t look like an accident, it wasn’t clear what it was. Ramirez quizzed each of his fellow homicide detectives: “Anybody worked a case like this?”

RELATED: Austin bomber case remains open

Back at police headquarters, more people appeared in Chief Manley’s doorway. Each update was more worrisome than the last. The interim chief canceled his morning appointments, hustled into a Ford Explorer with an assistant and swung north toward Interstate 35.

The quiet street at the center of the Harris Ridge neighborhood was soon jammed with idling Austin Police Department squad cars and, by midafternoon, a long row of federal police sedans. Agents from the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) regional office combed the grass for tiny bomb fragments. Putting all those pieces back together might be their only way to track down whoever had just blown up Anthony Stephan House.

What happened that day sparked a manhunt unlike anything Austin had ever seen. Over the next 19 days, more than 500 federal and local police joined in a deadly race to figure out who was planting bombs across a city that grew more afraid with each explosion.

The trail ultimately led to a 23-year-old with no previous bomb-making experience or training.

The bomber’s reign of terror overshadowed what is generally an upbeat time in Austin when the city takes the world stage during SXSW festival. Instead of the usual glowing festival coverage, national media headlines described a city gripped by fear.

A year later, officials have shared the fullest account so far about an investigation that was equal parts old-fashioned police work and high-tech surveillance. They also acknowledged the anxiety that stalked their bustling command post in East Austin, even as they urged residents to be vigilant, but calm.

“It was a terror that held over a long period,” Chief Manley said.

In the end, what solved the case was classic law enforcement teamwork: Armed with Texas motor vehicle records, ATF explosives expertise and the results of dogged legwork across Central Texas, a mid-level civilian FBI analyst would ultimately connect the key puzzle pieces that led authorities to the Austin bomber.

A bombing baffles police

In the days after House’s death, detectives knocked on every door up and down Haverford Drive, looking for clues. Did anyone have security video? Did they see anything suspicious?

They spent hours looking at neighbors’ nighttime video to see if they could spot something -- a car, a figure, anything out of place -- only to be met with disappointment after disappointment.

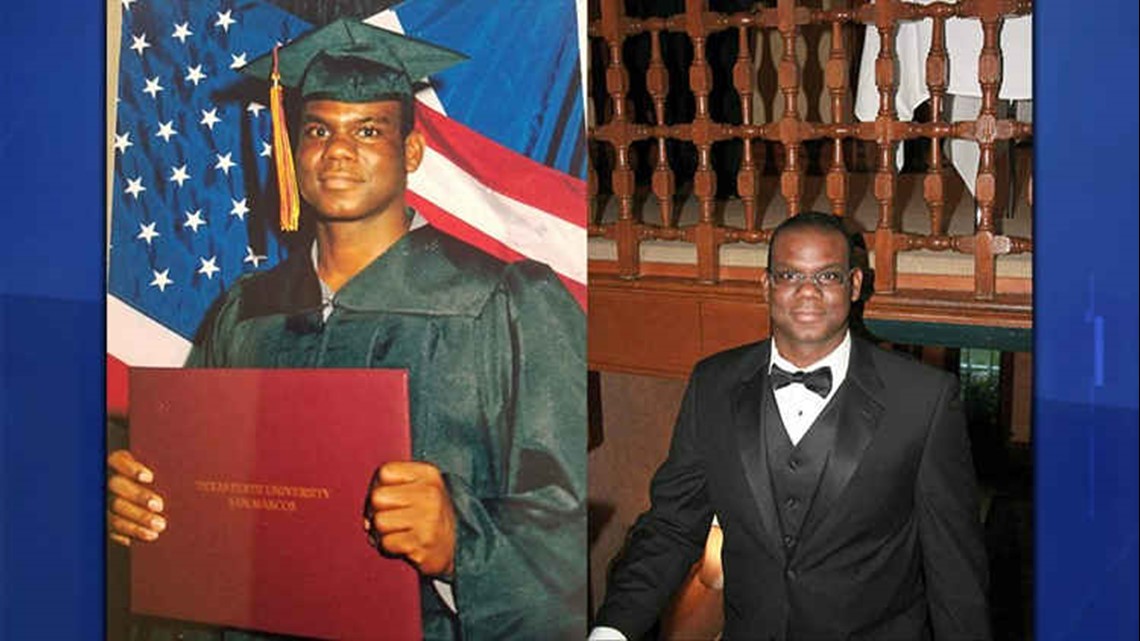

They dug into House’s past. He was a married father of a young daughter and graduate of Pflugerville High School and Texas State University. Family and friends described him as humble and unassuming.

Investigators turned to the possibility that his death was the result of mistaken identity. Only a few days before the bombing, Austin police had dismantled a drug ring in the neighborhood. They wondered whether the blast may have been tied to that case.

At a news conference several days after the attack, reporters asked Assistant Police Chief Joe Chacon about other motives behind the blast. He responded that police had so little to go on that they could not conclusively call House’s death a homicide. As part of a range of possibilities, Chacon mentioned that House may have been handling explosives, creating the bomb himself, and that the blast was accidental -- an idea that sparked anger in House’s family and friends. They said there was no way he could have done such a thing.

“I do not believe that we have somebody who is going around leaving packages like this,” Asst. Chief Chacon told reporters.

As police ran down leads on House and Haverford Drive, fragments from the bomb were flown on a federal jet to Washington, D.C. Within 48 hours, ATF experts rebuilt the device, reverse engineering its design to identify everything the bomber used, down to the brand of nails and batteries. Packaged in a box no bigger than a book, the bomb was designed to go off when a box flap was opened.

“The sooner we can identify someone who has bought multiple components, the better chance we have of identifying the individual who is responsible for all of this,” said Fred Milanowski, a 30-year veteran agent who leads the regional ATF that includes Austin.

Over the next week, agents visited every Lowe’s, Home Depot and mom-and-pop hardware store within an hour of Austin, from Georgetown to San Marcos, along I-35. Armed with federal subpoenas, they methodically checked each store’s records for information about recent sales.

The effort yielded truckloads of store receipts and inventory records. In a sterile, fluorescent-lit conference room just off the main command post, federal employees gathered around laptops and spent days typing all of that material to build a database they could search by name and by item.

Agent Milanowski urged the agents not to rush to judgment, repeating what became a mantra: “Ninety-nine point nine percent of those people are absolutely innocent.”

As a young ATF agent, Agent Milanowski had been one of the hundreds of federal investigators assigned to the Olympic Park bombing investigation in Atlanta. The 1996 case remains infamous because its would-be hero, a security guard named Richard Jewell, was falsely identified as the main suspect.

Decades later, that remains a potent cautionary tale for veteran agents such as Agent Milanowski.

In Austin, investigators collected and parsed all the data, evidence and thousands of leads. The devil was in those details. Somewhere in the reams of print-outs and receipts, there was information that would eventually lead to their big break.

‘Operation Austin Bomb’

On March 12, it became clear Austin was under attack.

Chief Manley had been up since the wee hours. One of his officers had been involved in a shooting, and he had been out at the scene most of the night. He decided not to go home and instead got a jump-start on his day.

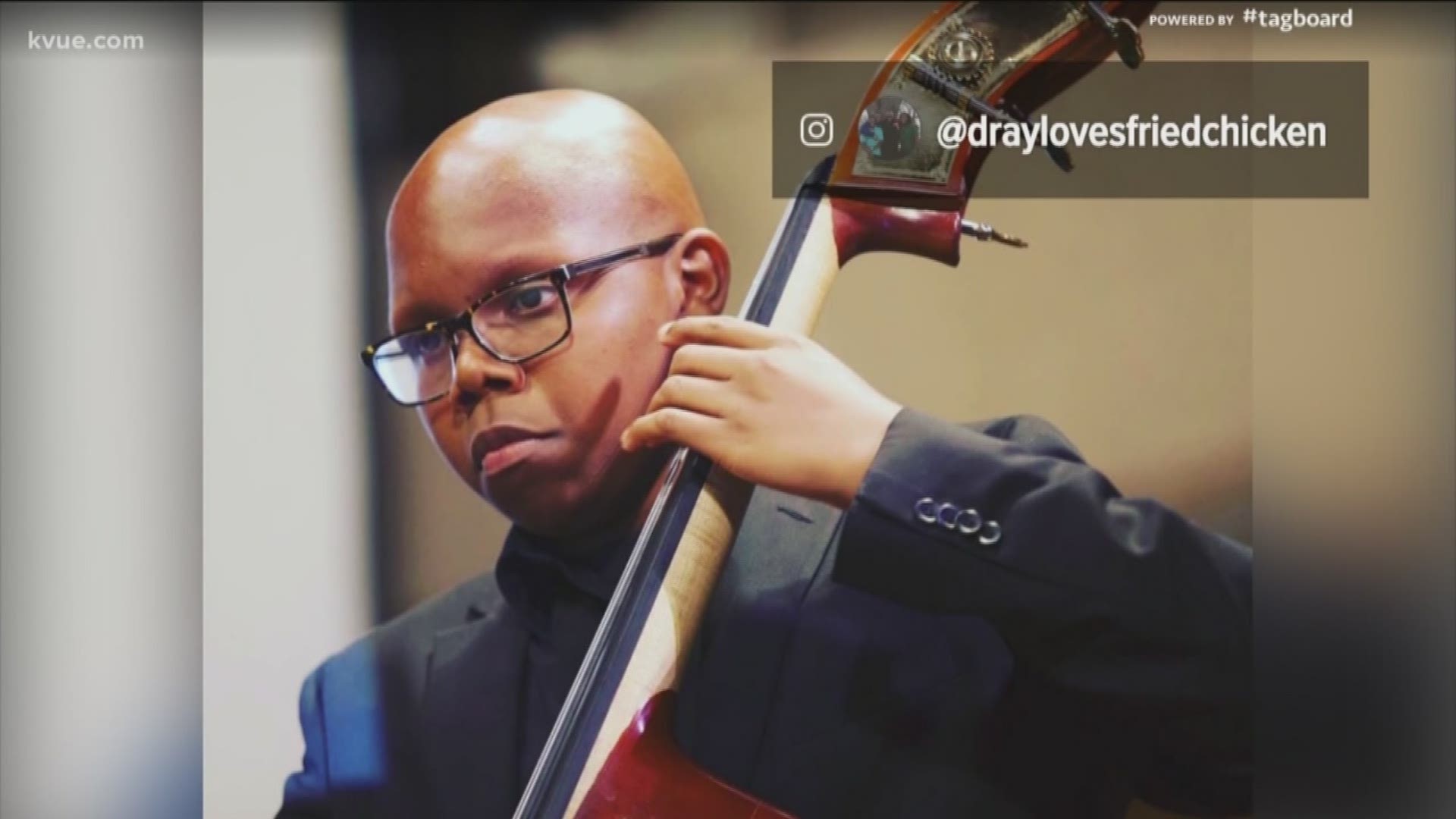

He was at his desk, plowing through emails around 7 a.m., when his cell phone rang. Again, it was the department’s on-duty watch commander with more disturbing news: A teen -- later identified as 17-year-old Draylen Mason, a promising classical musician -- had been killed in a bombing. His mother had been seriously wounded.

For Chief Manley, it was a sucker punch. He kept circling back to the same awful thought: Someone is attacking our city.

Det. Ramirez thought dispatch was mistaken when he got the call. Because he was already investigating the first blast 10 days earlier, he continued as the lead detective in Mason’s death.

Both Chief Manley and Det. Ramirez went to Mason’s house in Central-East Austin. Inside, damage from the blast stretched from floor to ceiling, so powerful it blew out the kitchen cabinets.

Det. Ramirez stared at the remnants. He had been in Central Texas since his parents moved the family from Los Angeles. After graduating from high school in Boerne, he joined APD in 1999, working every part of the city. He couldn’t quit wondering what kind of person would work so methodically and randomly to kill and frighten this famously laid-back, friendly town. Why Austin? Who is doing this? Why now? What were the attackers trying to say?

As Chief Manley stood outside the house with a growing team of federal agents, he caught sight of grim-faced commanders striding toward him.

It had been about five hours since the morning’s first bombing. Now, the commanders told him, there had been another one -- in another part of East Austin, six miles away. That blast critically wounded a 75-year-old woman.

Esperanza “Hope” Herrera, who lay wounded at Dell Seton Medical Center, told family members she thought the cardboard box, taped shut, was her elderly mother’s mail-order medication.

Chief Manley wondered if someone was dropping bombs throughout the city, toying with authorities and turning the arrival of a package into a game of Russian roulette for the more than two million residents across the region.

How many more deadly boxes had been dropped on front steps or slid into mailboxes? How many more of his citizens were going to pick up an ordinary package and get blown apart?

Chief Manley grabbed his phone and pecked out a message to the public on Twitter: “If you receive a package that looks suspicious or that you are not expecting, DO NOT open it. Call 911 immediately. Help us spread this message.”

ATF agents analyzed the two blast fields and quickly realized it was the work of the same person.

“Once a bomber figures out a way to make his devices and make them go off and has his success, he doesn’t change,” Agent Milanowski said.

The FBI declared the bombings a major case and dubbed it “Operation Austin Bomb.” With that designation, hundreds of agents from across the country streamed into Austin.

Special Agent in Charge Chris Combs, the lead FBI agent in Central Texas, worried Austin had a serial bomber on its hands.

“We have to jump into this with everything we have,” he said. “We can’t continue to have bombs going off in Austin.”

For the next seven days, investigators focused on two theories: a bomber was targeting minority residents, and the victims were connected.

RELATED: 'I saw her on the ground, all bloody,' mother of Austin bombing victim says in exclusive interview

Friends and family of the victims told investigators that House’s father-in-law, the Reverend Freddie Dixon, was good friends with Dr. Norman Mason, Draylen Mason’s grandfather. Detectives scoured property records and found someone lived on the same street as the blast that injured Herrera with the last name “Mason.”

After days of plowing through hundreds of tips, investigators thought they were gaining traction. Information that authorities still won’t specify led them to two men, and the clues were strong enough to tag both as persons of interest.

“You are looking at not only the components in the device, but cell phone towers, a cell phone that might have been in the area, and so you start looking at things,” Agent Milanowski said. “You look at people’s backgrounds, maybe a threat that they had made in the past.”

Undercover surveillance teams began monitoring both of the men around the clock.

Investigators also wondered if they should reach out to the bomber to try to establish a dialogue or gain hints about who he was targeting and why.

“Bombers typically have a message,” Agent Milanowski said. “They typically communicate sometimes with the media and sometimes investigators because they want to get their message out.”

To try to establish a dialogue with him, they held a news conference on the afternoon of Sunday, March 18, when they also announced a $115,000 reward.

Then they waited to see what the two potential suspects would do next.

Closing in on a killer "He was very good at what he was doing, which is why our job was so hard.”

Two weeks after Austin had its first bombing attack, investigators thought they were close to their big break.

Two names had bubbled up from a huge list based on receipts for possible bomb-making equipment. Police watched the two men around the clock. They hoped to catch one or both going to a store to buy bomb-making items. Instead, they watched two Austinites carry out mundane tasks.

A new bombing on March 18 -- the city’s fourth -- changed everything.

Chief Manley, then Austin's interim police chief, had been at the city’s 24-hour command center, a gated bunker in East Austin, most of the day. He decided to meet his family at their favorite Italian restaurant for dinner.

Midway through his chicken parm, his phone rang. Two men had just been injured in a blast in southwest Austin.

RELATED:

Will Grote and Colton Mathis, high school friends in their early 20s, had been biking in the Travis Country neighborhood when the bomb went off. Paramedics rushed both to the hospital with leg injuries from shrapnel. Grote was left with permanent nerve damage.

As Chief Manley raced to the scene, investigators wondered whether the explosion could have been the work of a copycat. The bomber had not left a package on a doorstep, but instead used a trip wire anchored by two white-on-red “Drive Like Your Kids Live Here” signs to detonate his bomb.

Hundreds of FBI and ATF agents had already been dispatched to work “Operation Austin Bomb,” including two specialized national response explosives teams.

Austin was jammed with SXSW tourists, forcing agents to commute from far-flung suburban hotels.

ATF agents combed the scene of the attack in Travis Country and determined that the latest device bore the same hallmarks of the other three: a metal pipe and explosive powder encased in a PVC pipe and surrounded by shrapnel. It was powerful enough to blast through a wooden fence lining the street and leave a pool of blood on the sidewalk from one of its victims.

It marked the first time the bomber had struck west of I-35 and in a predominantly white neighborhood. That forced investigators to change their working theory that the bomber was targeting minority residents – or anyone in particular at all.

“This is a jump in sophistication,” Agent Combs, from the FBI's San Antonio regional office, said. He has been with the agency for 23 years and assigned to national units dealing with terrorism and weapons of mass destruction. “This is a jump in lethality. And that concerned us greatly. That was a whole other situation -- he’s raising his game and taking it to another level.”

Investigators also realized that connections between the previous victims were just a coincidence. The first victim, Stephan Anthony House, was connected to the second victim, Draylen Mason, who was killed 10 days later, through House’s father-in-law. But they were all just family friends. A Mason found in property records had no connection to Draylen Mason or his family.

Even as the latest attack revealed new information about the bomber’s apparently random attacks, it frustrated investigators.

They had focused hard on the possibility that one of two men they had been surveilling for a week was the bomber. But neither of the men had been anywhere near the site of the fourth attack.

“Everyone felt like we had good persons of interest based on the information we had, and to see that evaporate, there is a moment of defeat,” Chief Manley said. “Everyone just dug back in and doubled down and worked that much harder because we recognized it wasn’t going to stop. The need was even greater to keep digging.”

The bomber reveals himself

As investigators regrouped, only one thing seemed certain: the bomber could change course again to throw them off.

“I hate to commend a bomber, but he was very good at what he was doing, which is why our job was so hard,” Agent Combs said.

Investigators worked into the evening that Monday, but kept running into dead ends.

Late that night, they got their most substantial clue yet.

Agent Fred Milanowski, the leader of the regional ATF office, who started his career as a small-town police officer in Michigan, got back to his hotel room and had only been asleep one hour when an agent woke him just before midnight.

A bomb had gone off at a FedEx distribution facility in Schertz, about 65 miles south of Austin. This time, no one was badly hurt.

Agent Milanowski lifted his head off his pillow and thought, “‘Oh my goodness, I have to get a whole team who has worked just as hard all day long out to that facility.’”

Thanks to FedEx’s sophisticated tracking system, investigators quickly learned that the bomber had shipped the bomb at a FedEx store in a strip center on Brodie Lane in Sunset Valley, just southwest of downtown Austin.

Within 30 minutes, investigators laid eyes on the new suspect for the first time. Store security video captured the man sending the same package that later exploded in Schertz. He wore blue jeans, a green T-shirt and had a blonde wig with a black cap. Even more oddly, he wore pink construction gloves on a warm spring day.

Their momentary excitement at laying eyes on the suspect was quickly replaced with a new fear. The bomber had shown he was sophisticated enough to build an explosive that could be shipped through a private carrier or the U.S. postal system.

They wondered if he had shipped any other packages, perhaps even out of state, through the mail system or another carrier.

“All of whom use planes to fly parcels across this country,” Chief Manley said. “The concern was, ‘Where are there any other potential parcels?’”

The records showed the bomber had indeed sent a second explosive that day at Brodie Lane FedEx. And they needed to find it before someone else did.

Using the company’s tracking system, they traced the second package to a FedEx facility in southeast Austin. A police bomb team had to detonate the device to render it safe, eliminating the possibility of gathering fingerprints or analyzing the ink in handwriting on the shipping label.

By 8 a.m., investigators were at the FedEx store on Brodie Lane, awaiting the employee who interacted with the bomber. He told them, “‘That guy was very strange. In fact, he smelled like burnt wire,’” Agent Milanowski recalled. The employee told agents he never considered the man might be the Austin serial bomber. He knew that person had been dropping packages at doorsteps, not shipping them.

But the FedEx employee was suspicious enough that he followed him to the store’s front door. Peering through the store display window, the clerk watched a man climb into a red pickup truck and drive away.

An analyst makes a discovery

The energy at the command post ratcheted up.

Agents showed the FedEx employee a photo lineup of pickup trucks to see if he could pick out the bomber’s truck. He pointed to a red Ford Ranger.

Investigators raced to the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and requested a spreadsheet listing the name and address of every Texan with a red Ford Ranger. They knew there would be thousands.

While they waited, Jordana Nesvog, a civilian FBI analyst, crouched over her laptop and plowed through tips in the farthest corner of a windowless room, just down a hall from the main command post.

She had been with the bureau for a dozen years, signing on as an analyst after getting hooked on the idea of solving mysteries as an elementary student who loved 'Nancy Drew.' She worked big cases, too. While based in Denver, she was one of the dozens of bureau personnel who gathered evidence after the Aurora movie theater massacre in 2012.

Nesvog had transferred to Austin five years earlier, and much of her FBI work in Texas involved drug and gang investigations. As part of a regional bureau emergency response team, she had joined the bombing investigation early on, helping to gather evidence at the scene of the Galindo Street bombing. She was then detailed to the bomb case command post, where she and everyone else put in 12- to 16-hour days.

On the night of the FedEx explosion, her cell phone pinged constantly with grim updates about the bomber’s latest attack. Just after dawn, she pulled her hair back into a ponytail, donned her FBI polo shirt and headed back to fire up the laptop she had left only a few hours earlier.

She later recalled a clear feeling as she badged into the command post: This is going to be the day.

Surrounded by four-foot stacks of files and papers, Nesvog felt another surge of optimism when she heard that agents had figured out the make and model of truck the suspect drove. She had helped identify key evidence in drug investigations by tracing cars to suspects. Again, she later recalled, she could feel things clicking into place: We are going to figure this out.

Early that afternoon, Nesvog pitched to her supervisor that they might discover a name by cross-referencing vehicle ownership records with their database of bomb component purchases. It was a long shot, but still worth a try.

While she waited for technicians to develop codes to merge the databases, she picked up a batch of store sales records near her computer. Thumbing through them, she typed a customer’s name from the first receipt into the massive database and hit “search.”

"No match found."

She typed another name.

"No match found."

Five more names: "No match found."

The name on the seventh receipt was Mark Conditt.

She typed it in. Her heart raced.

There was a hit. The vehicle registration database flagged Conditt as the owner of a red Ford Ranger and revealed he also lived in the Austin area.

Nesvog grabbed the store receipt, looking closer to see if Conditt had bought any of the items found in the bombs. “You have that little voice in the back of your head that says, ‘That was too easy. It can’t be that easy.’”

Nesvog turned to a colleague, interrupting his phone call with an agent in the field.

“I think I found something,” she told him. “We need to get a boss.”

Within seconds, a group of investigators and supervisors clustered behind her, staring down at her computer screen as she explained her discovery.

“From there,” Agent Combs said, “it was off to the races.”

The final explosion “We have to get this guy now."

Investigators who had devoted weeks to finding the Austin bomber moved fast in the hours after getting their most promising lead 18 days after the first bombing. An FBI crime analyst had matched a suspect’s name with store receipts showing he bought the same items found in his explosive devices.

Property records showed he lived at a house just off Main Street in Pflugerville. He had no criminal record. His social media footprint was barren. Internet searches revealed no ties to radical groups.

The highest-ranking officials overseeing the investigation decided it was time to make their move. They hoped to get warrants to raid his house and arrest him. Nervous about information seeping out, they hand-picked a small team of investigators from two federal agencies -- the FBI and the ATF -- and the Austin Police Department to present their case to top leaders and prosecutors.

They crammed into a small conference room. Standing at a dry-erase board, APD Homicide Det. Rolando Ramirez and several federal agents began listing everything linking the suspect to the bombings.

U.S. Attorney John Bash and Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore scrutinized their work.

“Things were moving fast,” DA Moore said. “Our attention turned to, ‘We’ve got to do this right. Everything has to be perfect. We have to be solid.’”

Investigators started with the biggest clue: The suspect drove a truck like the one a FedEx employee saw after the disguise-wearing bomber shipped two explosives.

By then, investigators had also gone through hours of security video from a Fry’s in North Austin. There was footage of the suspect strolling through the electronics aisles, tossing five batteries with “snap connectors” into a shopping basket -- just like the kind found in the bombs. Investigators then matched the customer in the security video with a driver’s license photo of a clean-shaven young man in glasses. That left little doubt the suspect had been out shopping for bomb parts three days before the first explosion.

Investigators had also learned the suspect had bought five “Drive Like Your Children Live Here” signs on March 13 at a Home Depot in Round Rock, identical to the ones used to anchor a tripwire in the Travis Country blast five days later. In the same purchase, he bought a six-pack of pink work gloves that matched the pair the bomber wore to the FedEx store.

Based on the time of his Home Depot purchase, investigators backtracked and found more security video. Once again, the customer looked like the same person in the suspect’s driver license photo.

“There is information coming in so quick that even the command wasn’t aware of all the information,” ATF Agent Fred Milanowski said. “Once they got to about the sixth thing that tied this person, I was like, ‘That’s our guy. Now the big question is: Where is our guy?’”

Praying for a ping

In the same small room, prosecutors frantically typed out warrants to arrest the suspect and search his home. There were also search warrants for the suspect’s cell phone and internet provider, which would help investigators learn more about his computer searches and track him with his phone’s GPS.

“There is that moment of relief because when they outlined on the whiteboard all of the connections, everything that made them believe that the bomber was in fact the person who he turned out to be, it was readily apparent that he was,” Police Chief Brian Manley, who was interim chief at the time, said. “But you still have that sense of concern because he wasn’t accounted for yet.”

By that evening, undercover agents were parked outside Mark Conditt’s yellow wood-framed house on North Second Street. The suspect’s father had bought the '50s era fixer-upper months earlier and put his son’s name on the deed, telling acquaintances it was to be a father-son renovation project. Two roommates, who Conditt had found through online postings, shared the house.

As they staked out the house, surveillance teams got close enough to see the same 2002 red Ford Ranger in the driveway and snap photos of items in the bed.

Conditt left the house before police were ready to move in and never returned. Investigators later learned he spent the rest of his final day working at a garage door repair company, then heading to a public library in Round Rock. He spent several hours on the internet, surfing on the library’s public computers, possibly trying to determine whether he’d been identified as a suspect.

“I think in some form or fashion, he was concerned we were potentially closing in on him,” Chief Manley said.

Chief Manley and Agent Milanowski huddled with FBI Agent Combs. They had to figure out how to move forward quickly, but avoid spooking the bomber. They also had to prepare contingencies for dealing with someone who’d repeatedly proven he was willing to kill.

Around 5 p.m., officials dispatched an ambulance to a nearby park on Pflugerville Drive to await police action. Officials suspected the bomber might have booby-trapped his house with explosives, so they needed first aid close by when they moved in.

But the medics either got confused or received incomplete instructions. They knocked on the door of the suspect’s house, thinking they were being sent to a medical call. They spoke to one of the suspect’s roommates before realizing their mistake. After they reported what had happened to the command post, investigators feared the roommates might tip off the suspect.

Officials weighed what to do next. Go ahead with the search, or wait until daylight, when it would be safer?

Everyone agreed it was best to hold off. Chief Manley fought the inclination to second-guess that decision. His biggest fear was that the bomber would be out planting more explosives after they went home to sleep.

That night, he thought his worst fear had become a reality when news broke about an explosion at a Goodwill Store on Brodie Lane. Given its proximity to the FedEx store where the bomber had shipped two explosives, officials thought it may be connected to the serial bombings. But that small blast turned out to be from ammunition inadvertently left in items that a man had donated to the thrift shop earlier in the day. A false alarm that nonetheless further set the city’s nerves on edge.

RELATED: Explosion at Goodwill caused by 'artillery simulator,' not believed related to bombings: APD

By nightfall, investigators had a court order to put a tracker on the suspect’s phone and were monitoring cell towers across the city, praying for a ping.

Conditt had turned his cell phone off.

At the command post, investigators scattered to get what rest they could before a major operation at dawn. Chief Manley wasn’t ready to call it a night.

“There were very few people left in the command post, and I was just thinking through things,” he said.

Chief Manley noticed a cluster of animated investigators, so he strode over. Federal agents remember telling him the suspect had just powered on his phone long enough for its signal to beam back to the command post. It had pinged at a Red Roof Inn parking lot near I-35 in Round Rock.

Investigators knew they couldn’t wait for daylight.

“We have to get this guy now,” Agent Combs said.

A chase, a blast and a city exhales

Chief Manley dispatched undercover officers to the motel.

Agent Combs raced from his hotel toward Round Rock. En route, he called the Texas Department of Public Safety major he’d talked to dozens of times as the case unfolded. They needed every trooper anywhere near Round Rock to throw up a perimeter now.

“‘Get up there, surround that hotel, we’re coming,’” Agent Combs said. “'We need every resource you have.'”

SWAT Team members had trained nearly three weeks for a possible take-down but had been sent home for the night. They scrambled back and met in the Rudy’s BBQ parking lot near the motel around midnight.

There, they quickly ran through possible scenarios. He might’ve booby-trapped his truck. He could have a bomb under his seat.

Chief Manley and other officials leading the investigation gathered in a Chuy’s parking lot, a little bit further south along the interstate frontage road.

“We had already talked about, if he moves, we have to take him down,” Agent Combs said. “We can’t let him get away.”

The SWAT team members climbed into two white vans and awaited a go signal.

“We would have liked to contain him and gain control over him to give him the chance to peacefully surrender,” SWAT Team Sergeant Brannon Ellsworth said.

They were still awaiting a caravan of armored vehicles chugging up I-35 from police headquarters downtown when their radios buzzed. Just before 2 a.m., the suspect pulled his red Ford Ranger out of the motel parking lot.

Circling overhead, a DPS chopper equipped with a forward-looking, infrared video camera tracked the Ford Ranger as it backed out of a corner parking spot and picked up speed.

The DPS radio crackled:

“Air to ground, he’s on the move, backing out now.”

“Ten-four. Where’s he at?”

“I’ve got him eastbound, Wall Lane, coming up to 35 frontage.”

The DPS aerial camera captured the truck cruising down an empty four-lane and easing to a stop at a four-way intersection.

The aircraft swung around for a wide shot of the suspect’s truck and the growing police convoy behind him -- nine chase vehicles in all. The truck accelerated.

“Alright, we’re through the intersection, southbound, still on frontage, from Old Settlers. Look for the laser. I got it on him.”

SWAT officers inside two vans followed. Chief Manley and other officials joined the convoy, staying several car lengths behind.

“I’m thinking about all the ways this could transpire,” Chief Manley recalled. “You know, this is an individual who is willing to kill innocent people and the likelihood of him being armed, knowing however this played out, it was going to be a very dangerous operation.”

The 11 SWAT team members didn’t like how things were going. The suspect was heading south on the interstate frontage road, able to get back on the highway at an approaching on-ramp. They knew letting him onto the interstate would be even more dangerous.

It was time to act.

Sgt. Ellsworth radioed his lieutenant for permission to use one of the vans to knock the red Ford Ranger off the road and into a ditch.

The van’s driver sped up and slammed the truck’s back bumper. The impact sent the truck careening into the patch of grass separating the frontage road and I-35.

SWAT team members leaped from the vans and sprinted toward the truck. The first to reach the truck beat on the passenger window. He was in mid-swing for the third time, his partner close behind him, when the heat-sensitive video from the overhead chopper flashed white.

“Got an explosion, got an explosion inside the vehicle!”

In the chaos, Chief Manley and other officials checked on each SWAT team member one-by-one. No one was seriously hurt. Inside the Ford Ranger, Mark Conditt was dead, ripped apart by his final bomb.

Det. Ramirez soon arrived at the scene. As the sun came up that morning, the feelings of the past three weeks rushed in as he stood beside the suspect’s blown-out truck.

“I was angry because he made us go through all of this, the community, he took the peace away from Austin,” Det. Ramirez said. “It was senseless.”

‘I still want to know why’

As they dug through the remains of the truck, they found Conditt’s phone with a chilling, recorded statement that amounted to a confession.

“It’s me again…” he began.

In a rambling 28-minute monologue, Conditt called himself a psychopath and said he had been disturbed since childhood. He listed his mistakes, including going to the FedEx store. He detailed a plan to go into a crowded McDonald’s to blow himself up if police moved in on him. He ended with a chilling declaration: “I wish I were sorry, but I am not.”

They also found evidence that he was planning more attacks.

“He wasn’t done,” Agent Combs said. “He had plans to do other attacks of different size and capacity.”

Conditt never shared any of that with his roommates, who were questioned but not charged. Investigators would later learn that Conditt was so secretive that he kept a padlock on his bedroom door.

Over the past year, Det. Ramirez and a handful of federal agents kept investigating. They have tried to learn what made a 22-year-old young man spiral into an explosives-fueled killing spree.

“We also had a lot of work to do to make sure there were still not other people involved,” Chief Manley said.

They also struggled to understand how he had chosen the homes and the victims. The answer, Agent Combs said, is “only in his demented mind.”

Ultimately, they couldn’t answer the question that had haunted Austin.

“I still want to know why,” Chief Manley said.

With the investigation wrapped up, the chief refuses to utter the bomber’s name and the department will not release his 28-minute confession. Chief Manley wants any attention given to the case to stay on the victims and the massive effort devoted by hundreds in law enforcement to stop the Austin bomber. He also worries that the recording could serve as a tool to help future attackers.

RELATED: Inside The Story: New details about Austin bomber’s life reveal struggle with faith, sexuality

That morning last March, investigators again taped off a crime scene and combed the frontage road in Round Rock for the fragments that always revealed the bomber’s signature. But they knew the most urgent part of their work was done.

Chief Manley stayed on the roadside for several hours. He hadn’t slept for 26 hours.

As the sun rose on the grisly scene, he hoped that his city could start to feel safe again.