AUSTIN, Texas — The historic Lions Municipal Golf Course is 100 years old, and many want to ensure it continues as part of the community.

Sports can be an equalizer, and places can be too. For Volma Overton Jr. and Scotty Sayers, the combination of both brought them together.

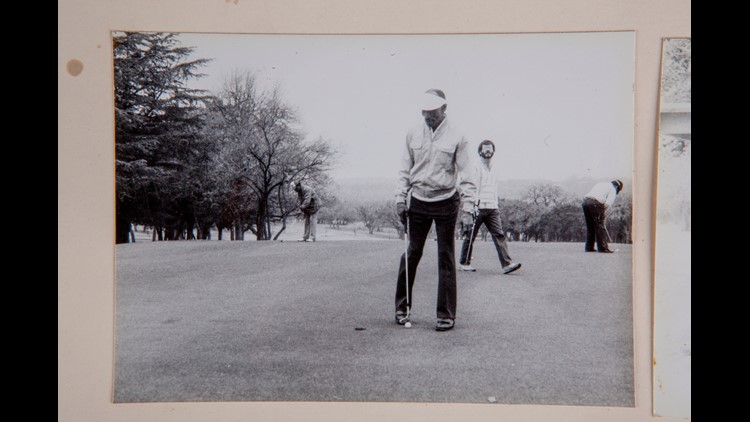

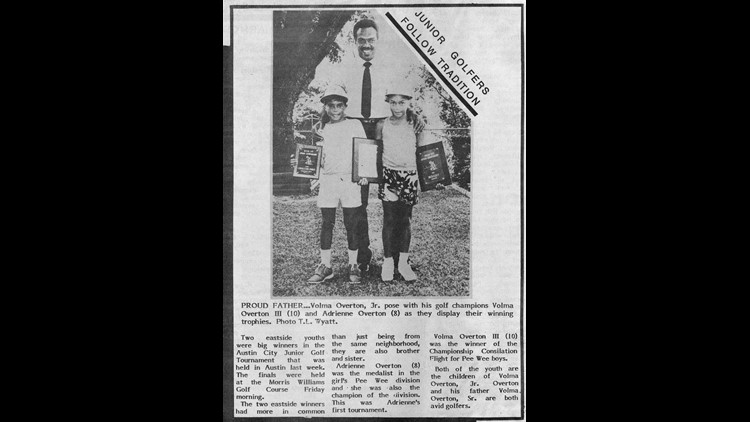

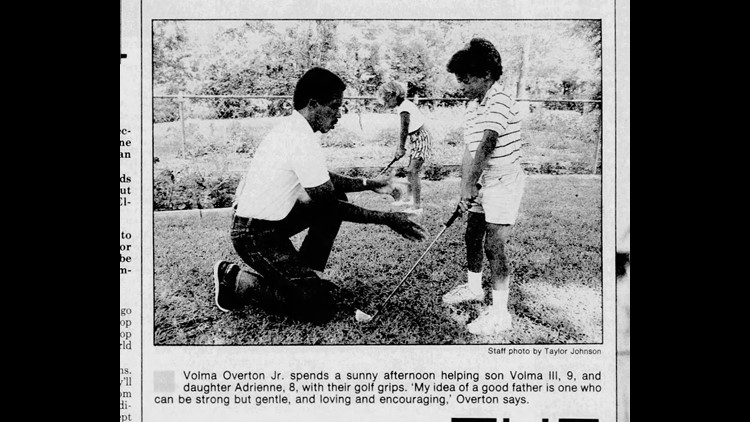

"We have four generations, soon five, that have played on this golf course," Overton said.

"There's no one place in this town that I'd rather be than out at Lions Municipal Golf Course," Sayers added.

Lions Municipal Golf Course, or "Muny," is where the two met their best friends and fell in love with golf. But their experiences at the start were different.

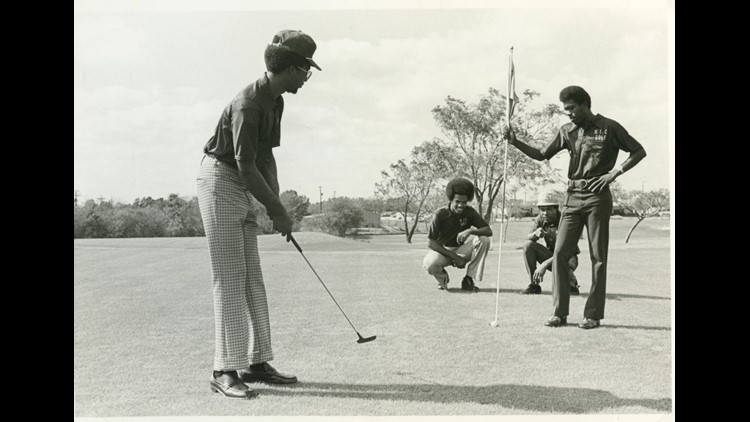

In the late 1950s, two Black boys as young as 9 years old went against the law and started hitting some balls at Muny. Little did they know it would lead to a monumental step toward desegregation in Austin.

"Almost 74 years ago, right here, is where this thing happened," Sayers said. "And the mayor said, 'Let them play.'"

Overton said his dad followed suit quickly after.

"My father and a couple of other friends say, 'Well, if they can play, we can play, too,'" Overton said. "So they started playing on a regular basis."

Months later, in 1951, Lions became one of the first courses in the South to voluntarily desegregate. A change then-4-year-old Overton remembers well.

Remembering desegregation at Lions Municipal Golf Course in the 1950s

"There were only actually three Black groups that played golf on this golf course," Overton said. "One time ... I was out here with my father, and I looked around, and that's when I said, 'Daddy, where all these people come from?' I'm talking about us people, you know. He said, 'Son, looks like the word's gotten out.' I remember that I was truly amazed about seeing so many Black people on the golf course, and it was full."

Sayers said it took three years for other golf courses in the South to desegregate. But it wasn't all birdies and holes-in-one at the beginning.

"It was integrated, but we couldn't come into the building for some time," Overton said.

According to Overton, at that time, Black people had to pay using a little window. If they needed to use the restroom, the caddie's shack was the only place they could go.

"Just like back in the day when you had a colored water fountain and a white water fountain ... Color water fountains are just nasty," Overton said. "And just kind of how the restroom situation was, that one toilet for all the golfers."

Overton said it wasn't until the late 1950s that that changed – but it didn't stop him from making some of his fondest memories. Shortly after the course's desegregation, Austin libraries and fire stations followed suit.

The course is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The fight to save Muny

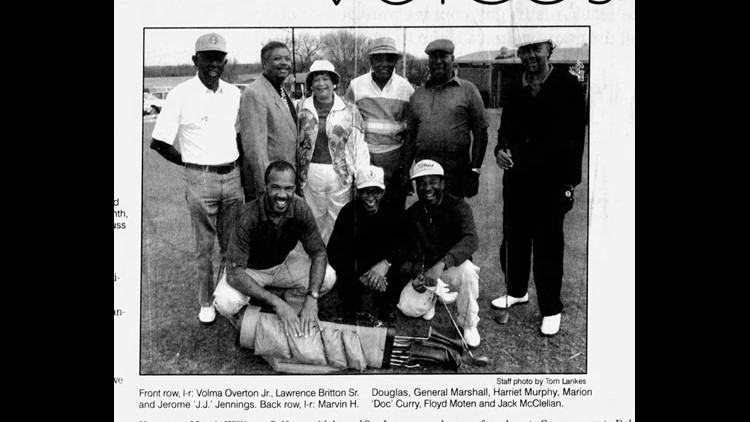

Overton and Sayers are on the Save Muny Conservancy Board, a nonprofit created in 2019 to preserve, restore and protect the iconic, recreational green space for future generations.

The course is 100 years old, but the 18 holes are in danger. According to Sayers, the University of Texas at Austin leases the greenspace to the city of Austin on a 5-month rolling lease.

The fight to save the 141 acres has been going on for decades. Sayers said they want to negotiate with UT to make sure both sides win.

"Lions sits on a valuable piece of real estate," Sayers said. "There's no question about that. This is 141 acres. It's a wildlife sanctuary. It's a water recharge zone. It sits over a water recharge zone."

Sayers said if they do come to a deal, the conservancy plans to turn part of it into a museum to recognize the Black history at Lions and renovate the course.

"I'm going to fight forever because I'm fighting for my kids and my grandkids and all these people that are out here every day," Sayers said.