AUSTIN, Texas — At the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865, 3.5 million enslaved Black Americans were freed. But even though the Emancipation Proclamation that ended slavery in the Confederacy had been issued several years earlier, it wasn’t until June 19, 1865 – the day later known as “Juneteenth” – that word reached Texas when Union General Gordon Granger announced the order to the people of Galveston.

As the news spread across Texas, 250,000 enslaved people suddenly faced the reality of having to figure out how to make a home for their families, put food on the tables and create a better future for their children.

Yet, following the Civil War, matters could not have been more difficult. Confederate states like Texas were determined that ex-slaves would neither be truly free nor equal. Jim Crow Laws and Black Codes created the framework for a strict system of racial segregation and white supremacy.

By 1870, Black citizens made up 30% of Texas’s total population of 800,000. But there had been so much violence carried out against them, many would travel to bigger cities where federal troops could offer protection. And for many, that meant a trek to Austin.

Many Black Americans in Central Texas would settle in what were known as Freedman’s Communities. At one time, Austin had 15 separate enclaves where Black Americans lived close together, establishing their own businesses, schools and churches.

There was Clarksville, established by Charles Clark in 1871, home to hundreds of freed slaves. And Wheatville, established by James Wheat in 1869, where the first Black newspaper west of the Mississippi was published after the Civil War. It was called “The Gold Dollar” and was printed in a building that stands today on Austin’s San Gabriel Street, surrounded by student condos on the University of Texas' West Campus.

But those all-Black communities like Clarksville, Wheatville, and other enclaves scattered around the city would eventually lose most of their population. In 1928, the Austin city government developed a plan that would force Black Americans out of their homes scattered around the city and force them to move to the east side of town.

To ensure that people would make the move, City Hall warned that it would not provide paved roads or sewer lines in the former all-Black neighborhoods but promised to do so on the east side.

Black citizens were to merge into a single neighborhood, forced to settle into what city planners called the "Negro District."

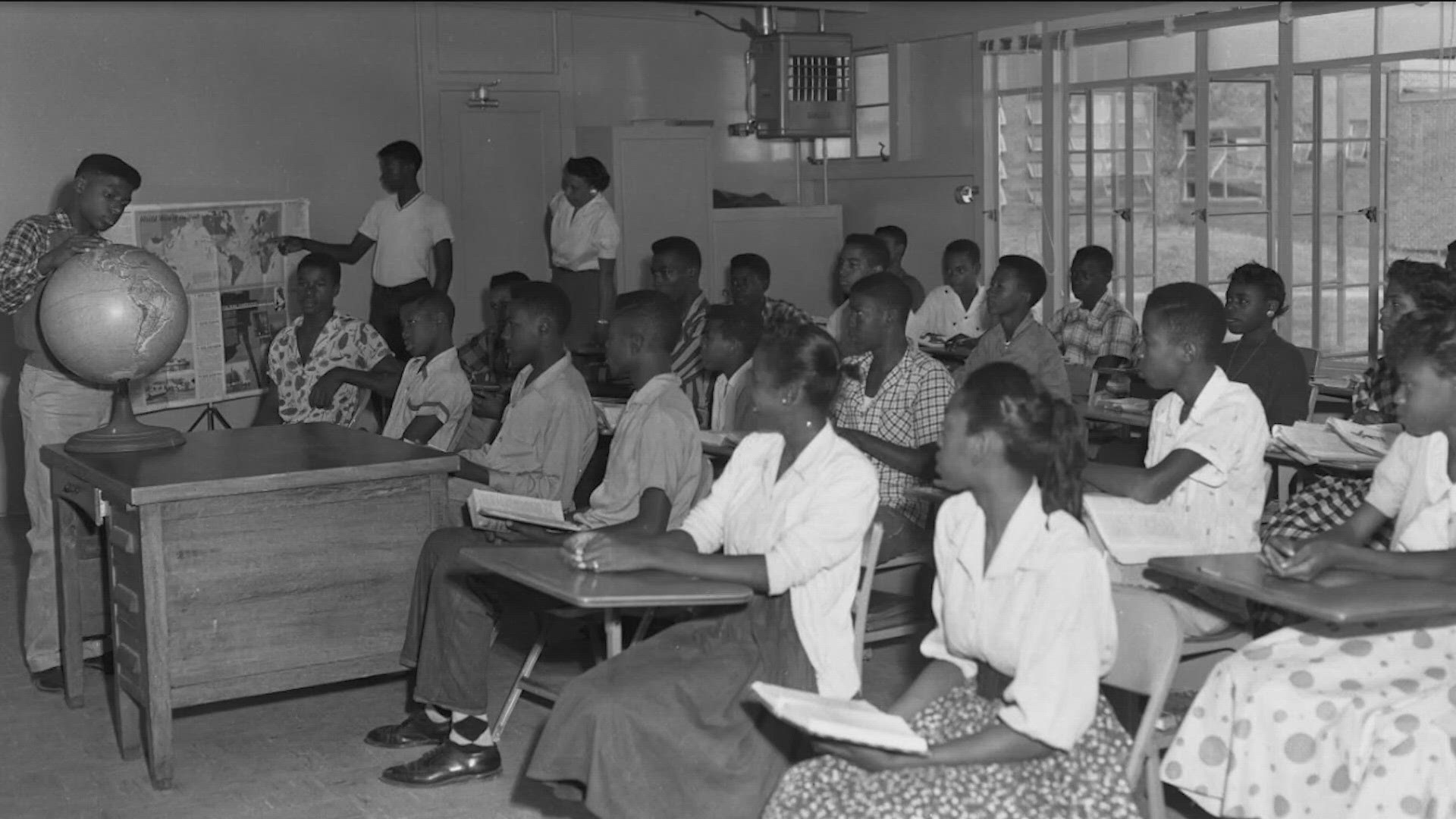

Austin’s East Eleventh Street would become the focus of a thriving Black business community. From the 1940s on, East Austin developed into a center for Black-owned stores and professional services, cultural life and education – all in a community bonded together by neighborhood churches.

RELATED: Huston-Tillotson hopes to partner with Austin ISD to address lack of Black male educators nationwide

But by the 1950s, East Austin found itself isolated from the physical and psychological barrier created by the opening of Interstate 35. The freeway replaced the beautifully landscaped East Avenue, which had been an open and accessible boulevard that linked the east and west sides of town. For many, I-35 created a concrete barrier between the prosperity of downtown and the neighborhood on “the other side.”

But there were positive changes in the 1950s, too: a growing awareness on the part of politicians and the courts that Black Americans deserved the same opportunities as whites.

With the passage of Civil Rights legislation and the Voting Rights Acts of the 1960s, Black participation in political life took on new urgency.

The first time a Black American was elected to public office in Austin was in 1968 when Wilhelmina Delco won a spot on the city’s school board. In 1974, she was elected to represent Austin in the Texas Legislature until she retired in 1995.

In 1971, Austin elected its first Black city council member, Berl Handcox, as voter registration projects became a centerpiece of East Austin political life.

It was this period that marked the beginning of the exodus of Austin’s Black population from the east side. Historian Lisa Byrd has written that even before the gentrification of the past 20 years that forced many long-time families to move away, Black families started migrating to the suburbs and smaller communities surrounding Austin in the 1970s.

For Black Americans in Austin – past and present – there has been a long history of struggles and triumphs, with so many new chapters of that history yet to be written.