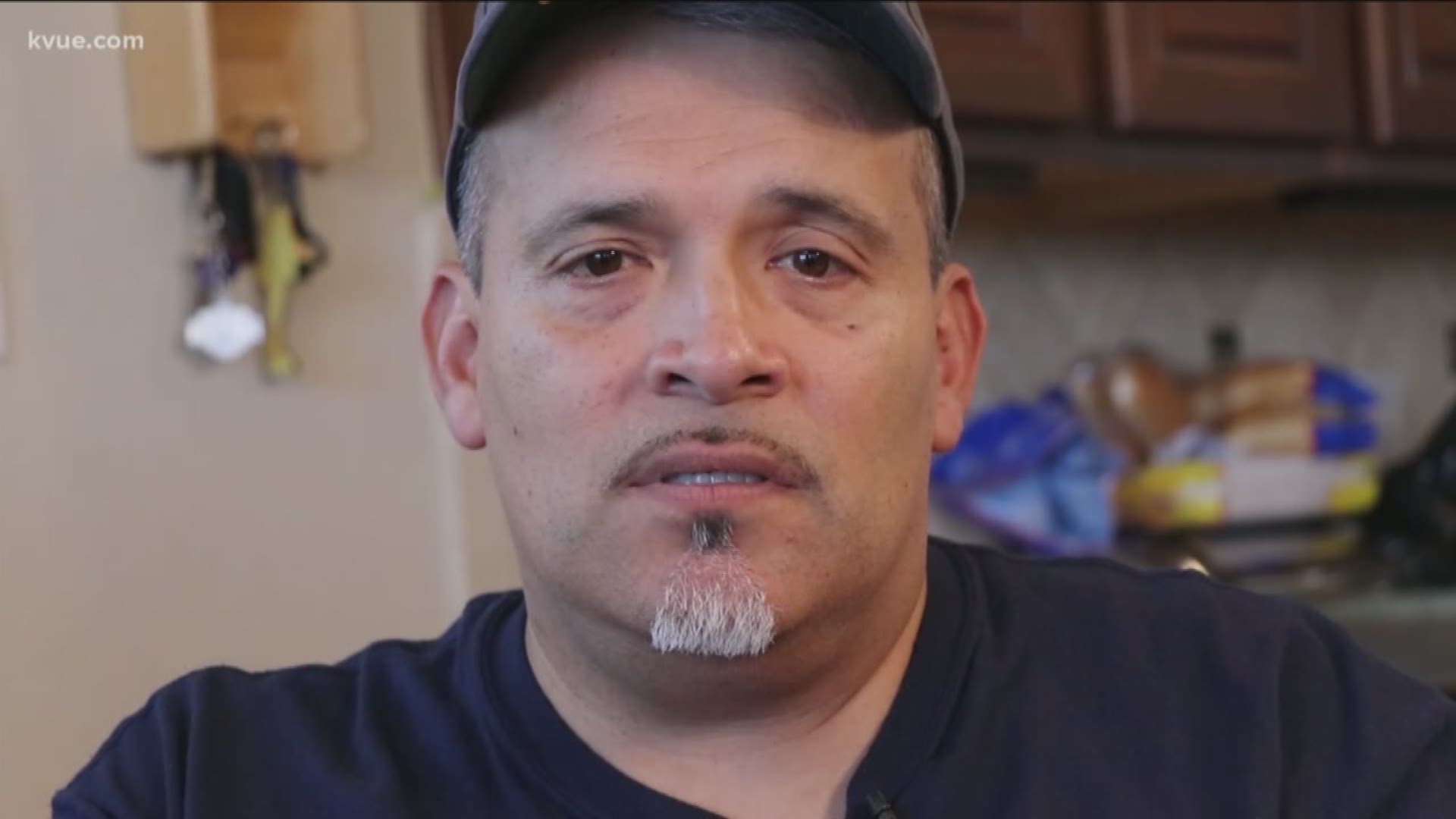

CENTRAL TEXAS — Louis Ugarte’s heart doesn’t pump what it should. He has cardiomyopathy, which is 100 percent connected to his time in the U.S. Air Force.

But government red tape is putting the Central Texas veteran’s life at risk.

“My medicine is attached to me. It’s on this bag and pump. I’m still able to semi-function,” said Ugarte.

“The heart medicine that they have me on gets pumped straight into my heart. It lasts 48 hours. So, every 48 hours I have to change out my medicine bag and the pump along with it.”

The VA said they’ll pay only if Ugarte goes to a VA transplant centers. But that would mean traveling to Salt Lake City, Utah. Still there, the surgery would not be at a VA center, but a contracted university hospital.

The KVUE Defenders first told you about problems in the Veteran’s Affairs organ transplant program in 2016. We pushed for change to help our veterans.

RELATED:

Congress took action and passed the Veterans Transplant Coverage Act in 2017, plus the VA Mission Act in 2018.

The Transplant Coverage Act says a veteran can receive an organ from a non-veteran and the Mission Act guarantees a veteran can get local transplant care.

But it’s not happening, according to VA whistleblower Jamie McBride.

“Our veterans deserve the best care we can give them,” said McBride.

The KVUE Defenders exposed how the distance creates delays and denials in transplant care.

Researchers found veterans, like Ugarte, are more likely to die if they have to travel hundreds of miles for a transplant.

The Cleveland Clinic researchers agreed. In a separate study, they added VA patients are more likely to die because the distance impacts how long they’re on a waiting list. Patients who get care locally get it faster than veterans who live hundreds of miles away.

“There is nothing wrong with Salt Lake. it’s beautiful and the facility and the doctors, there’s nothing wrong with it, if we lived there,” said Ugarte.

The Mission Act was signed into law by President Trump last summer to create nationwide contracts between the VA and hospitals.

The contracts would cover the cost of getting an organ and performing the surgery locally.

But seven months later, the new contracts still aren’t ready, and McBride said VA headquarters refused to share how the old contracts work.

If it did, the Central Texas office could write one locally for Ugarte’s care.

“We’ve had to try to re-create (contracts) from the ground up, and transplant is a very long process. If you have to re-create the wheel, this contract can take up to two years,” said McBride.

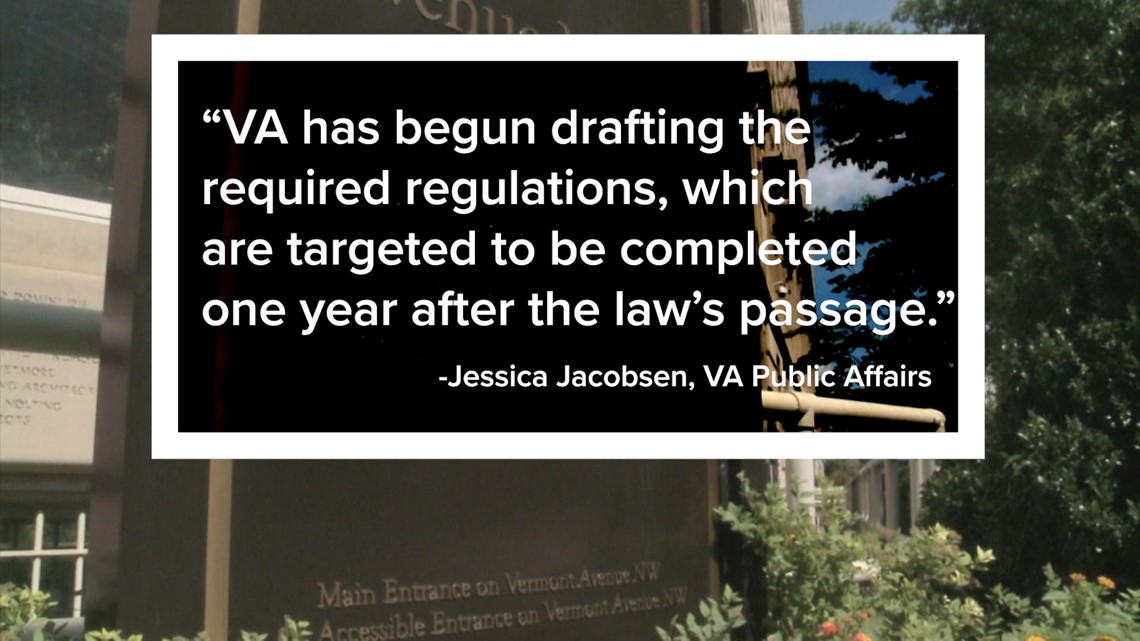

Jessica Jacobsen, Director for the Dallas Office of Public Affairs for the VA, issued the following statement:

“VA has multiple methods to pay for community care, and the policy you reference applies to two of them – traditional community care (fee basis) and the Choice Program. Both of these methods have limitations."

While the veteran has been offered transplant at the nearest VA transplant center, the South Texas Veterans Health Care System understands his mobility limitations and is additionally pursuing care options in the local community.

To make this process easier to navigate for Veterans, families, VA employees and community providers in the future, VA is rewriting the regulations governing how the department pays for all forms of community care – including transplants – in conjunction with the MISSION Act, landmark legislation that will consolidate Choice and VA’s other community care efforts into a single program. The regulations are scheduled to be completed one year after the law’s passage.”

We asked general questions about the process, how it would impact all veterans.

DEFENDERS: What is the VA doing to implement the new law (VA Mission Act)? Would it guarantee care for transplant patients who have an unusual or excessive burden to travel?

JACOBSEN: The VA MISSION Act establishes multiple criteria to receive care in the community. To implement requirements under the MISSION Act for the consolidated VA community care program, VA has begun drafting the required regulations, which are targeted to be completed one year after the law’s passage.

DEFENDERS: However, a VA whistleblower says Central Office will not share their contracts with them.

JACOBSEN: The premise of this allegation makes no sense, as the regulations governing community care under the MISSION Act are not yet complete, and per the law, VA has until one year after the law’s passage to complete them.

DEFENDERS: Why would the VA not cover procurement if the donor is deceased?

JACOBSEN: VA is still drafting regulations regarding the MISSION Act’s new community care authorities, but VA’s existing community care authorities allow VA to pay for transplant care in the community, including organ acquisition costs, whether the donor is living or deceased. In some instances, however, the rates VA can pay for such transplant-related costs are limited by statute, for example, the Choice Act. For this reason, VA typically relies on the authority in 38 U.S.C. 8153 to contract for transplant services with a community facility. This allows VA the flexibility to negotiate a rate acceptable to the community provider.

The new regulations are supposed to be in place by summer.

Ugarte may not have that long to wait.

If you have a story tip for the KVUE Defenders to investigate, send an email to defenders@kvue.com or call 512-533-2231.

Follow Erica Proffer on Twitter @ericaproffer, Facebook @ericaprofferjournalist, and Instagram @ericaproffer.