The legend of the bluebonnet

<p>How did this wild blue flower come to be so revered by millions of people across Texas?</p>

If the state flower of Texas had a Facebook page, under relationship status, it would say “complicated.” There is plenty of history between this flower and the Lone Star State.

Today, anyone who drives down a Texas highway can see the importance of this flower. The Texas Department of Transportation even has a wildflower program that buys and sows about 30,000 pounds of wildflower each year – with a large percentage of that going toward bluebonnets.

From a social standpoint, these admired flowers have become the epicenter of spring photos for couples, families and pets.

Springtime means Bluebonnets are blooming in Texas

But how did we get to where we are today? How did this flower become almost as big as the state of Texas?

The 'Lady in Blue'

The tale of the first Texas bluebonnet

There are multiple stories as to when and how the first bluebonnet appeared in Texas. Some of these anecdotes have more believability to them than others, but the one that has a special narrative to it comes from a history professor at the University of North Texas.

Randolph Campbell has been teaching at UNT for many years and is also the chief historian for the Texas State Historical Association. Pieces of his story revolving around the first bluebonnet can be found in his book “Gone to Texas.” His colleague, Donald Chipman, wrote “Spanish Texas," which includes this tale of the bluebonnet.

“You have at least three competing legends as to where the bluebonnets got their name from,” Campbell said.

Back in the early-to-mid-1700s, Spain was moving into the Albuquerque area of present-day New Mexico. There was a lot of missionary work going on between the religious leaders of this area – which led to an odd occurrence revolved around a Spanish nun named María de Jesús de Agreda. She was a member of the Poor Clares Order of Franciscan nuns and someone that the Jumano Indians said mysteriously appeared to them in Texas.

“She was wearing a blue cloak over her nun’s habit,” Campbell said. They called her the ‘Lady in the Blue.’”

These Indians claimed to have learned about Christianity from her, especially the symbol of the cross. María de Jesús de Agreda claimed to have miraculously and physically appeared in two places at once – Texas and New Mexico – without ever leaving her convent in Spain.

“There was the claim that she had been part of a miraculous bi-location,” Campbell said.

The Texas legend concerning the “Lady in the Blue” came from the Jumano Indians, who said that the nun’s spirit left behind something blue and something powerful in their fields.

“The Indians said that on the morning after her last visit, they awoke to find a field covered with flowers that were deep blue – the color of her cloak,” Campbell said. “They call this the legend of the first Texas bluebonnets.”

Becoming our state flower

And the group of women who made it happen

The bluebonnet has been the Texas state flower for 116 years; but during March of 1901, this was not a forgone conclusion.

According to Jean Andrews -- author of the book, “The Texas Bluebonnet” -- the state legislature struggled to decide what the state flower was in 1901.

“The previous year, the Senate had passed a resolution with little conflict,” Andrews wrote. “But, in the House, debates were flying fast and furious as one legislator launched his appeal for his favorite, to be followed by more eloquent protestations of the virtues of yet another.”

The three main flowers on the table were being advocated for by three areas of Texas. It was generally believed that West Texas wanted the Prickly Pear Cactus, Central Texas lobbied for the bluebonnet and East Texas pushed for the Cotton Boll.

One issue for Central Texas, though, was many of the legislators didn’t know what a bluebonnet even was.

“Someone replied that it was that blue flower that looked like those old-timey sunbonnets the pioneer Texas women wore in futile attempts to protect themselves from the burning sun and winds of Texas,” Andrews wrote.

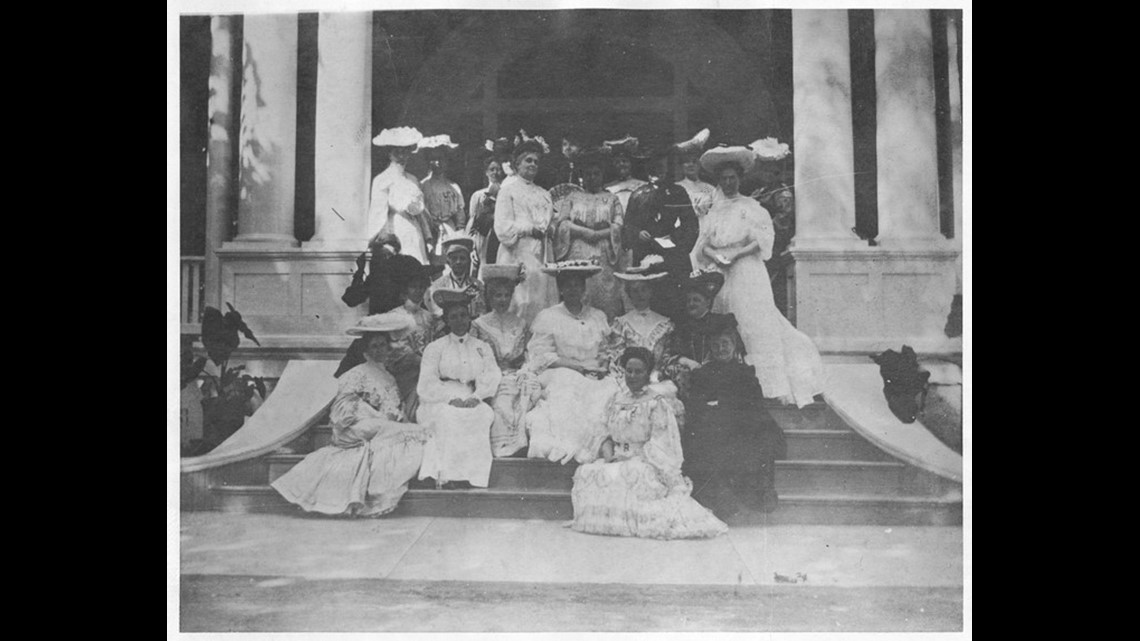

However, there was a group of women who knew exactly what this flower was – the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America of Texas. Rowena Dasch works at the Neil-Cochran House Museum today and is a member of this organization.

“They decided to take matters into their own hands to the degree they could,” Dasch said in reference to the Colonial Dames from that time period. "They were watching this and thinking, 'You've got to be kidding me. It can't be the Prickly Pear. It can't be the Cotton Boll."

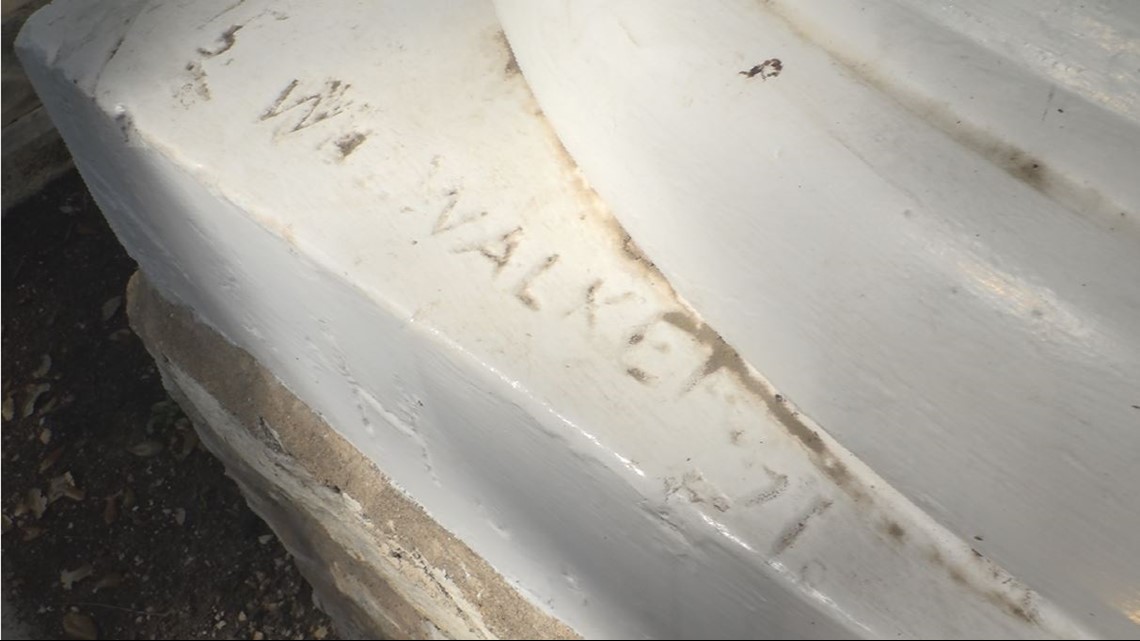

These women called a local artist, Mode Walker, and asked for one of her paintings of the bluebonnets.

"They went over to her studio, picked it up, carried it off to the Capitol and put it on display on the floor of the legislature,” Dasch said.

Yet, a painting wasn’t enough for these determined women; they were going to go the extra mile to make sure they made their point.

"They had little jars of bluebonnets that they placed on each politician’s desk before the vote,” Dasch said.

With the painting on the floor and the flowers on the desks, Andrews wrote that the decision became a simple one – the bluebonnet would be the state flower of Texas.

“The bluebonnet won hands down,” Andrews wrote. “It was approved by Governor Joseph D. Sayers on March 7, 1901.”

Deciding what type of bluebonnet counts

The 70-year debate

You might think at this point, the state flower could sail off into the sunset as Texas’ beautiful blue symbol. However, the ensuing debate would last decades upon decades.

PerriAngela Wickham moved to Texas as a little girl and grew up with a family who loved everything about the bluebonnet. Now living in Washington D.C., she travels to Texas every bluebonnet season to take photos or videos of the sights.

She also is well-versed in the fight that took place after the bluebonnet became the state flower in 1901. The original bill designated Lupinus subcarnosus as the official state flower, a type that mainly grows in the coastal and southern areas of Texas. There were many other varieties the legislators were not aware of at the time.

“Those were the flowers that were in the painting that the ladies brought to the legislature,’ Wickham said. “The problem was adopting that bluebonnet – that was not the most dominant bluebonnet in Texas.”

So a debate quickly ensued about which species could represent Texas. The main form of flower that many people and groups continually advocated for was the Lupinus texensis, which is what most people in Central Texas see today with the blue pedals and white tips. However, there were still many other varieties that stayed on the table.

“As time went on, they were like, ‘Wait a minute, this isn’t the bluebonnet that should be the state flower,’” Wickham said. “The fight went on for 70 years, trying to get the Central Texas bluebonnet listed as the state bluebonnet.”

On March 8, 1971, a resolution finally came together that not only included the Lupinus texensis, but all other forms of the flower as well. The official resolution comes from the 62nd Texas Legislature and reads, “Bluebonnet, LUPINUS TEXENSIS and any other variety of bluebonnet.”

So that passion and fervor for the bluebonnet -- it has been there from the beginning. Year after year, the legend seems to grow grander than what it used to be. This flower has a folklore to it – it has a life of its own. One that will continue to live on in the heart of our state.