WASHINGTON — If the USA wants to attract more young women into advanced math and sciences, two top federal officials said Wednesday, the first step is to acknowledge that, well, Houston, we have a problem.

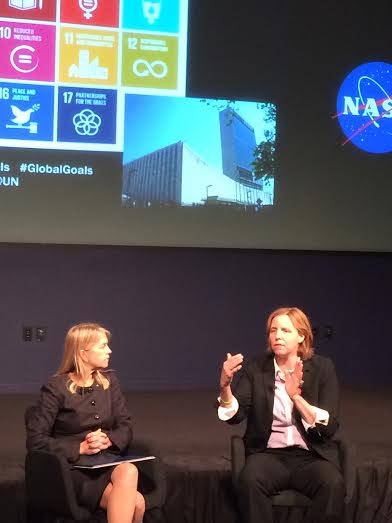

Appearing at NASA headquarters as part of a “United State of Women” Summit, NASA Deputy Administrator Dava Newman noted that fewer than one-third of the agency’s scientists, and just over one-fifth of its engineers, are women. “It’s atrocious,” she said. “So we have to call it what it is.”

She recalled that she and colleagues had recently started a blog featuring women of the space agency and said, “There’s 10 NASA women that we don’t think even NASA women know about.”

Though female students have made huge strides overall in education — they now outnumber men on college campuses, for instance — Newman said a few trends are still worrisome, such as the low percentage of girls taking Advanced Placement (AP) computer science courses each year. Given current course-taking trends, she predicted, “We’ll have people on Mars before I get 50% of the girls taking AP Computer Science.”

She added, “It’s good to celebrate and we’re all in this together, but I think the data does speak to us. The data really does speak to us.”

Megan Smith, U.S. Chief Technology Officer, said the problem is more deeply rooted than just too few women taking advanced math or science courses. Bias against women taking on top roles goes deeper, she said.

Smith noted a recent popular analysis of more than 2,000 Hollywood screenplays that found most were heavy on male dialogue. Even in romantic comedies, it found, the dialogue that was, on average, 58% male.

“It’s so amazing who’s getting to speak in film,” Smith said. “Every time we’re watching TV, women and men are kind of learning not to listen to women. And that’s what’s happening to us in meetings.”

Smith said Americans’ basic ideas about women’s contributions in tech fields are similarly skewed. She noted, for instance, that if you look at historic photos of the Silicon Valley team that developed Apple’s Macintosh computer in the early 1980s, “There are lots of women in them, together, in those photos, even though for some reason we keep writing movies with casts that are all male.”

Among the unsung Apple pioneers, she said, is Susan Kare, who helped develop the Mac’s elegant user interface.

Recent government statistics suggest a decidedly mixed picture for young women and science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) studies. Girls are actually taking many key high school STEM courses at a slightly higher rate than boys: Nearly half of female high school graduates take advanced biology, for instance, compared with just 39.4% of boys.

And in the past generation or so, girls’ access to higher education has grown rapidly. In 1994, the Pew Research Center found, just 63% of female high school graduates enrolled immediately in college, slightly higher than the proportion of males at 61%. But by 2012, Pew found, the share of young women enrolled in college immediately after high school had grown to 71%. For males? It stayed unchanged at 61%.

An estimated 11.5 million females now attend college, outnumbering men at 8.7 million, federal statistics show.

But young women are not earning many advanced math and science degrees. A 2015 report from the non-profit National Student Clearinghouse Research Center found that women earned just 21% of computer science doctoral degrees in 2014, unchanged from a decade earlier. Women earned more science-focused doctoral degrees in only a few areas: biological/agricultural sciences, social sciences and psychology.

“We really do need to change the conversation,” Newman said. “I’m an aerospace engineer. I was never taught by a female — as a matter of fact, I’d never met a female aerospace engineer. So if you can’t see yourself, then it’s hard.”

She suggested that schools do a better job of making STEM field pathways less cutthroat and making STEM courses more exploratory — and with more teamwork, which accurately reflects what real scientists do.

“We filter people out,” she said. “We need to filter people in.”

Follow Greg Toppo on Twitter: @gtoppo

![636016059960600612-smith-newman-pic.jpg [image : 85945944]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/2016/06/15/USATODAY/USATODAY/636016059960600612-smith-newman-pic.jpg)