WASHINGTON — President-elect Joe Biden's pick of Lloyd J. Austin to be secretary of defense is stirring unease in Congress, reflecting fears that putting a recently retired general in charge could further undermine the centuries-old principle of civilian control of the military.

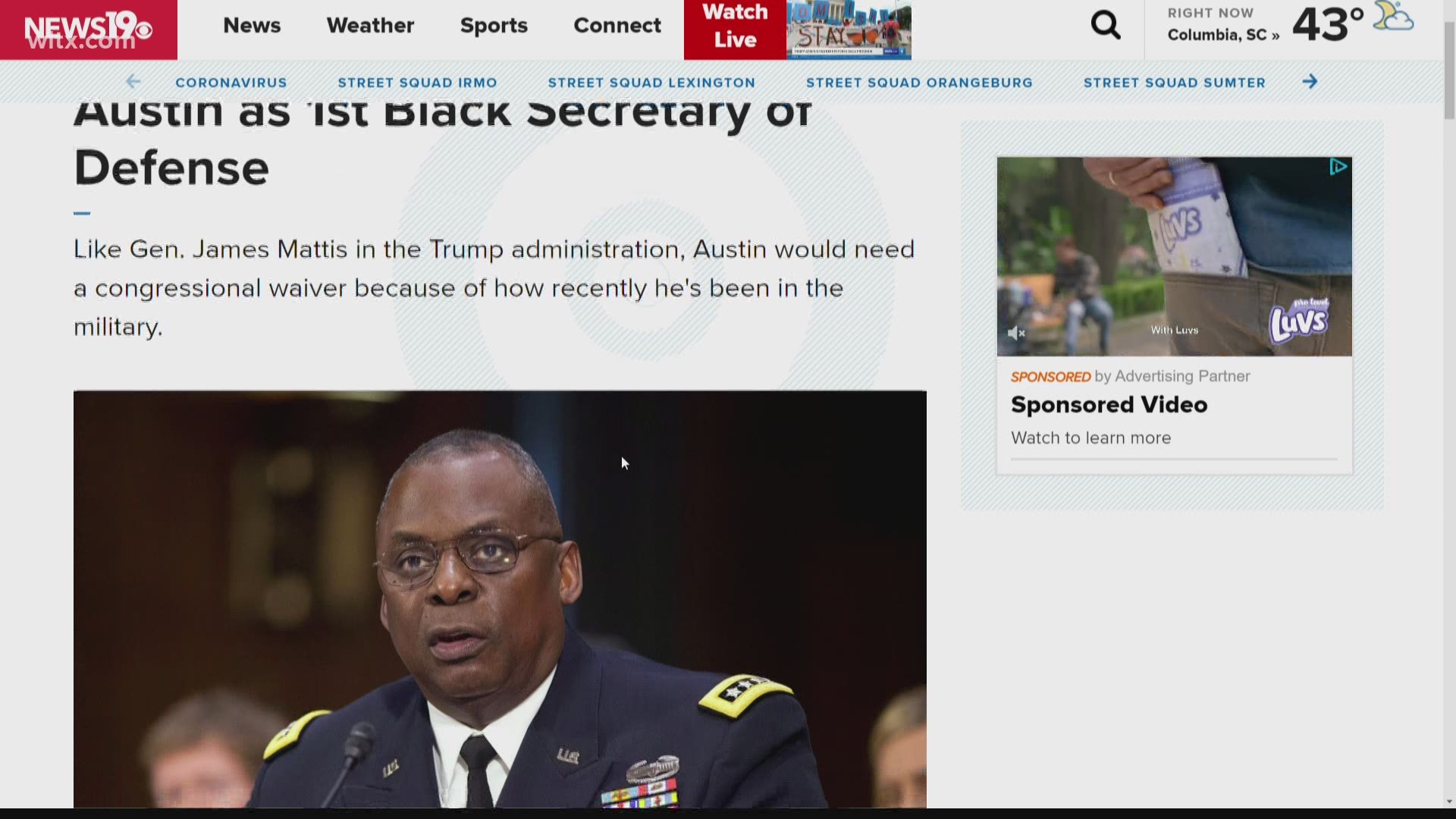

Biden publicly announced his choice Tuesday afternoon. Austin would be the first Black leader of the Pentagon, and the historic nature of the nomination, particularly in a year of extraordinary racial tension in the country, adds an intriguing dimension to the debate in Congress over one of the key members of Biden's Cabinet.

Austin was an unexpected choice. Most speculation centered on Michele Flournoy, an experienced Washington hand and Biden supporter. She would have been the first woman to run the Pentagon.

“General Austin shares my profound belief that our nation is at its strongest when we lead not only by the example of our power, but by the power of our example," Biden said in a statement announcing plans to nominate the retired four-star general.

Austin is widely admired for his military service, which includes leading troops in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan and overseeing U.S. military operations throughout the greater Middle East as head of Central Command. But getting him installed as Pentagon chief will be more complicated than usual. He must win a congressional waiver of a requirement that a defense secretary be out of uniform at least seven years before taking office. Austin retired in 2016 after 41 years in the Army and has never held a political position.

Such a congressional waiver has been granted only twice: in 1950 for George Marshall and in 2017 for Jim Mattis, the retired Marine general who became President Donald Trump's first defense secretary. Some prominent Democrats opposed the Mattis waiver, and among those who voted for it, Sen. Jack Reed of Rhode Island expressed doubts.

“Waiving the law should happen no more than once in a generation,” Reed, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Armed Services Committee, said then, adding, “Therefore, I will not support a waiver for future nominees.”

Asked Tuesday about an Austin waiver, Reed seemed open to the possibility.

“I feel, in all fairness, you have to give the opportunity to the nominee to explain himself or herself,” he told reporters.

Sen. James Inhofe, R-Okla., the current chairman of the Armed Services Committee, said he had no problem voting for the waivers. “I always support waivers,” he said. But he said he doesn’t know Austin well.

Civilian control of the military is rooted in Americans’ historic wariness of large standing armies with the power to overthrow the government it is intended to serve. That is why the president is the commander in chief of the armed forces, and it reflects the rationale behind the prohibition against a recently retired military officer serving as defense secretary.

The defense secretary's top military adviser is the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, currently Army Gen. Mark Milley.

Some Democrats who agreed to the 2017 waiver saw Mattis as tempering Trump's impulsive nature and offsetting his lack of national security experience. Now the Mattis period at the Pentagon is viewed by some as an argument against waiving the seven-year rule for Austin. Mattis critics say he surrounded himself with military officers at the expense of a broader civilian perspective. He resigned in December 2018 in protest of Trump’s policies.

Similar concerns may emerge with an Austin nomination.

Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut said despite the historic nature of the nomination, he would not vote for a waiver because it “would contravene the basic principle that there should be civilian control over a nonpolitical military."

“That principle is essential to our democracy … I think (it) has to be applied unfortunately in this instance,” he said.

Rep. Elissa Slotkin, a Michigan Democrat, said she has mixed feelings, including deep respect for Austin, with whom she worked as a Pentagon official during his years in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“But choosing another recently retired general to serve in a role that is designed for a civilian just feels off,” she said. “The job of secretary of defense is purpose-built to ensure civilian oversight of the military."

Slotkin said the last four years have thrown that out of balance. She said she wants to know how the Biden administration will address her concerns before she votes for a waiver.

One of the people who confirmed Biden's decision said the selection was about choosing the best possible person but acknowledged that pressure had built to name a candidate of color.

Biden has known Austin at least since the general's years leading U.S. and coalition troops in Iraq while Biden was vice president. Austin was commander in Baghdad of the Multinational Corps-Iraq in 2008 when Barack Obama was elected president, and he returned to lead troops from 2010 through 2011.

Among Austin's many military assignments, in 2009-2010 he ran the joint staff during a portion of Navy Adm. Mike Mullen's term as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Mullen had high praise for Austin.

“Should President-elect Biden tap him for the job, Lloyd will make a superb secretary of defense,” Mullen said in a statement. “He knows firsthand the complex missions our men and women in uniform conduct around the world. He puts a premium on alliances and partnerships. He respects the need for robust and healthy civil-military relations. And he leads inclusively, calmly and confidently.”

Austin, a 1975 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, served in 2012 as the first Black vice chief of staff of the Army. A year later he assumed command of Central Command, where he fashioned and began implementing a strategy for rolling back the Islamic State militants in Iraq and Syria.

Ash Carter, who became defense secretary in 2015 during the early months of the U.S. military's counter-IS campaign plan, wrote after leaving office that when Austin briefed him on a plan to retake the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, he found it lacking.

“I admired Austin's desire to take the fight to the enemy,” Carter wrote, “but the plan he presented to me was entirely unrealistic, relying on Iraqi army formations that barely existed on paper, let alone in reality.”

__

Lemire reported from Wilmington, Del. AP writers Lisa Mascaro, Matthew Daly and Zeke Miller contributed to this report.