Your cell phone rings. You don’t recognize the number on the screen, but the call appears to be coming from your area code – perhaps even your exchange. Maybe the display shows it’s coming from your town.

So you answer – and the unwanted recorded message begins.

A voice wants to sell you an extended warranty for your car, or a timeshare in a vacation spot, a loan to refinance your home.

It might even be a Chinese-language message about a purported package awaiting pickup at the local consulate.

Consumers, rejoice: An attack plan is nearing deployment against the billions of illegal robocalls that have made telephones and smartphones virtual weapons of mass frustration.

Emerging from a years-long effort by government, telecommunications and computer experts, the plan will use a verification system to stop robocall companies from masking the true numbers those billions of unwanted and illegal calls.

The tactic,known as spoofing, fools consumers by causing their Caller-ID systems to indicate falsely that the robocalls come from the phone numbers of familiar businesses, organizations, friends or acquaintances.

The verification system targets a problem that's a top priority for the Federal Communication Commission and the Federal Trade Commission.

The FTC last year identified robocalling as the number-one consumer complaint category: More than 1.9 million complaints against the practice were filed during the first five months of 2017.

U.S. consumers and businesses were barraged with roughly 30.5 billion robocalls in 2017, according to YouMail, a company that provides a service to block such messages. That broke the record of 29.3 billion calls set just a year earlier. And the company estimates the 2018 total will jump to roughly 48 billion.

The pace hasn't slackened. U.S. phones received some 6.1 million robocalls per hour in September 2018 alone, YouMail also reported.

Many robocalls aren't just annoying – they're illegal. Robocallers are not permitted to send telemarketing messages that haven't been approved by the recipients, or to dial numbers on the National Do Not Call Registry.

One robocall executive who has been sued by the FTCacknowledged that the growing torrent poses a problem.

"Obviously, the underlying issue is the calls are illegal," Aaron Michael Jones, affiliated with several robocalling companies, told an FTC investigative hearing in 2015. "We know that already."

Some robocalls are permissible. Government regulators have carved out exemptions for charities, for example, and also for political campaigns.

Major U.S. telephone service providers are expected to start integrating the verification system with their networks in upcoming months, with a more complete ramp-up to follow in 2019.

There's no agreement yet on what consumers will see in their Caller ID systems — a green check mark, perhaps, or another symbol to indicate the caller has the authorization to use the number that's displayed.

Participants in the anti-spoofing effort predict it will produce a progressive drop in robocalls."It will be an ongoing battle that will gradually get better," said Jim McEachern, principal technologist for the Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions.

He likened it to the effort that turned email spam from a similar aggravation into a relatively manageable problem.

Consumer advocates say the effort represents a good first step – but call for stronger safeguards.

Margot Saunders is senior counsel for the National Consumer Law Center. The verification system sounds promising, she said. But it's "just one piece of the overall robocall puzzle."

McEachern says he's seen a demand for solutions.

"The vast majority of my career, when I told people what I do, their eyes would glaze over," McEachern said. "Now, when I tell them what I'm doing, their eyes light up."

STIR and SHAKEN

The verification system is designed to correct an unforeseen problem that developed roughly two decades ago.

During the late 1990s, the telecommunications industry launched a technology capable of transmitting telephone voice calls via a broadband Internet connection instead of a regular phone line.

One of the support services to grow out of the technology was Voice Over Internet Protocol. Robocalls use VoIP because it's inexpensive. It also enables users to enter anything imaginable as the source of the call.

That identification, true or false, automatically is conveyed to consumers.

Jon Peterson is an expert in Internet and telephone operational protocols with Neustar, an information services provider with expertise in identity resolution. He has worked on the new verification system.

"You get email all the time from people who are not what it says in the header field," said Peterson. "You can kind of think of what we've developed as the next generation of Caller ID."

The developers have dubbed the system STIR and SHAKEN, a geeky engineering homage to fictional British spy James Bond's martini preference.

STIR, or Secure Telephone Identity Revisited, is a call-certifying protocol. SHAKEN, or Signature based Handling of Asserted information using toKENs, verifies the caller's right to use their phone numbers.

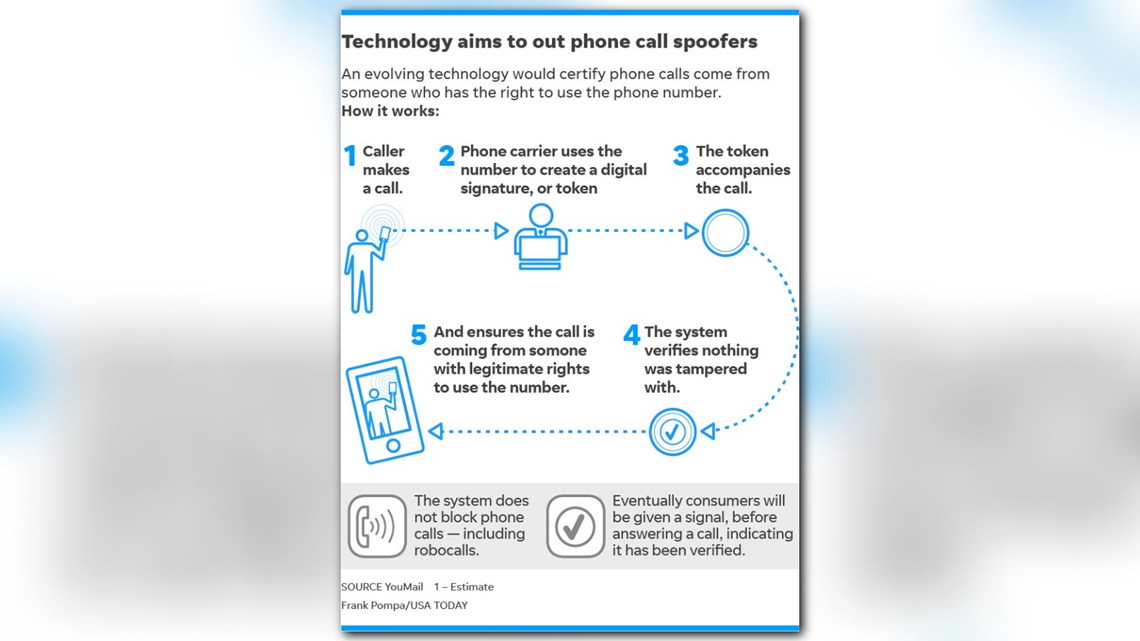

When you make a call, your phone carrier will use your identifying number to create a digital signature, or token, that will accompany the call as it is being completed.

At the other end, the system verifies that nothing was tampered with, and ensures that the call came from "someone who has a legitimate right to use that number," said McEachern.

However, the attack plan is no silver bullet solution.

It won't block any phone calls – including robocalls. Consumers eventually are expected to see an as yet undetermined signal that will indicate calls that have been verified, a feature intended to help guide decisions about whether or not to pick up.

The system also is expected to aid the work of companies that provide call-blocking apps for consumers. They already try to block robocalls by looking for calling patterns to identify calls from suspicious numbers.

The Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions on Thursday issued a request for proposals to get an administrator to apply and enforce the STIR and SHAKEN rules.

"Everything we're doing today is just going to be infinitely stronger once spoofing is eliminated," said Jonathan Nelson, a member of the research team and the director of project management for Hiya, an app company that provides Caller ID and spam protection services.

The Room Where It Happened

A team of telecom experts began discussing technological approaches to combating robocalls in 2013 with little notice from the outside world. The team included representatives of the giant traditional U.S. telephone providers, such as Verizon and At&T, and of cable and other companies that now offer phone services, such as Comcast.

As public outcry over robocalls mounted, a turning point in the team's planning came during a September 2015 workshop at the Federal Communication Commission's Washington headquarters.

The session included several experts working on the verification system, along with others from the telecom industry and public and private sectors.

Neustar's Peterson and Chris Wendt, Comcast Cable's director of Internet protocol communications services, recommended combining the STIR protocol started in 2013 by an international standards organization with the SHAKEN implementation system the team had started work on weeks before the FCC workshop. Other team members agreed.

Wendt said the consensus emerged from a collegial debate over technology: "I think this will work," he said team members agreed. "We have a plan to go forward."

Nonetheless, team members realized they needed the entire telecom industry, working together, to make the plan a working reality.

“Each provider is only as good as the other in the industry in stopping illegal robocalls. We need to get buy-in and help from big and small providers to fix this," said Martin Dolly, AT&T's lead member of technical staff, and a main figure in the anti-robocall effort.

The fears evaporated in July 2016, when the FCC spurred the creation of a robocall task force and directed major traditional and wireless phone providers to provide free call-blocking services to customers.

"That changed, in many ways, what was a bunch of techno-weenies toiling away in relative obscurity," McEachern said. "Suddenly the spotlight went on this activity as the most advanced effort to begin addressing the robocalling problem."

The work advanced in recent months with the creation of a panel of telecom company representatives that will continue to update the verification system as robocall companies seek ways to beat it.

The private sector approach would enable tweaks to be rolled out more quickly than if changes had to go through a lengthy government approval process.

"This would enable tweaks to keep the robocallers from being three years ahead of you, all the time," said McEachern.

Consumer advocates want the government to be more aggressive.

"Why is the FCC, given the exploding problem of scams and spoofed calls, and unwanted robocalls generally, not moving to require phone companies to implement caller authentication services across the board?" asked Saunders, of the National Consumer Law Center. "This should not be a voluntary effort."

Additionally, Saunders said, YouMail data show that scammers are not the largest source of robocalls. More come from debt collectors for banks or other companies – some of which, she said, are ringing up the wrong people.

"That also raises the question of should we be able to block other numbers, even those that are authenticated, that we want to stop calling us," Saunders added.

Who Pays?

The FCC says it does "not expect any carrier to directly charge consumers for the implementation costs of the service."

"While we are not mandating how carriers absorb these costs," the regulator said in a statement, "it would be more expensive for the typical carrier to attempt to allocate costs and bill subscribers individually."

The FCC also says it expects the system to reduce some carrier costs, "particularly with respect to customer service."

"These savings, as well as the goodwill from reducing the impact of robocalls on their subscribers, may more than offset the costs of implementation," the commission said.

U.S. Telecom, the trade group of the nation's broadband industry, does not expect major carriers will bill customers for the verification system.

Kevin Rupy, the group's vice president for law and policy, said some smaller carriers might need help with the cost and could seek assistance from the FCC's universal service fund.

Additionally, AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, Sprint and other major carriers have partnered with call-blocking and anti-spam partner companies to provide customers with increased protection, he said.