Humanity got its first glimpse Wednesday of the cosmic place of no return: a black hole.

And it's as hot, as violent and as beautiful as science fiction imagined.

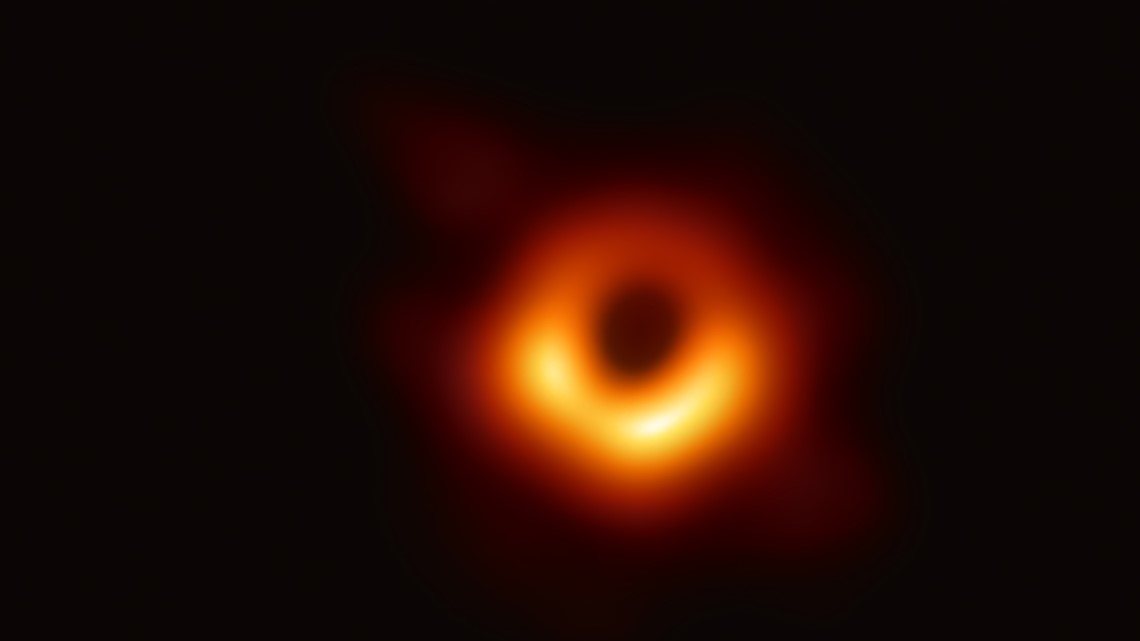

In a breakthrough that thrilled the world of astrophysics and stirred talk of a Nobel Prize, scientists released the first image ever made of a black hole, revealing a fiery doughnut-shaped object in a galaxy 53 million light-years from Earth.

"Science fiction has become science fact," University of Waterloo theoretical physicist Avery Broderick, one of the leaders of the research team of about 200 scientists from 20 countries, declared as the colorized orange-and-black picture was unveiled.

The image, assembled from data gathered by eight radio telescopes around the world, shows light and gas swirling around the lip of a supermassive black hole, a monster of the universe whose existence was theorized by Einstein more than a century ago but confirmed only indirectly over the decades.

Supermassive black holes are situated at the center of most galaxies, including ours, and are so dense that nothing, not even light, can escape their gravitational pull. Light gets bent and twisted around by gravity in a bizarre funhouse effect as it gets sucked into the abyss along with superheated gas and dust.

The new image confirmed yet another piece of Einstein's general theory of relativity. Einstein even predicted the object's neatly symmetrical shape.

"We have seen what we thought was unseeable. We have seen and taken a picture of a black hole," announced Sheperd Doeleman of Harvard, leader of the project.

Jessica Dempsey, another co-discoverer and deputy director of the East Asian Observatory in Hawaii, said the fiery circle reminded her of the flaming Eye of Sauron from the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy.

Three years ago, scientists using an extraordinarily sensitive observing system heard the sound of two much smaller black holes merging to create a gravitational wave, as Einstein predicted. The new image, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters and announced around the world, adds light to that sound.

Outside scientists suggested the achievement could be worthy of a Nobel, just like the gravitational wave discovery.

"I think it looks very convincing," said Andrea Ghez, director of the UCLA Galactic Center Group, who wasn't part of the discovery team.

The picture was made with equipment that detects wavelengths invisible to the human eye, so astronomers added color to convey the ferocious heat of the gas and dust, glowing at a temperature of perhaps millions of degrees. But if a person were to somehow get close to this black hole, it might not look quite like that, astronomers said.

The black hole is about 6 billion times the mass of our sun and is in a galaxy called M87. Its "event horizon" — the precipice, or point of no return where light and matter get sucked inexorably into the hole — is as big as our entire solar system.

Black holes are the "most extreme environment in the known universe," Broderick said, a violent, churning place of "gravity run amok." Unlike smaller black holes, which come from collapsed stars, supermassive black holes are mysterious in origin.

Despite decades of study, there are a few holdouts who deny black holes exist, and this work shows that they do, said Boston University astronomer professor Alan Marscher, a co-discoverer.

The project cost $50 million to $60 million, with $28 million of that coming from the National Science Foundation. The same team has gathered even more data on a black hole in the center of our own Milky Way galaxy, but scientists said the object is so jumpy they don't have a good picture yet.

Myth says a black hole would rip a person apart, but scientists said that because of the particular forces exerted by an object as big as the one in M87, someone could fall into it and not be torn to pieces. But the person would never be heard from or seen again.

Black holes are "like the walls of a prison. Once you cross it, you will never be able to get out and you will never be able to communicate," said astronomer Avi Loeb, who is director of the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard but was not involved in the discovery.

The telescope data was gathered two years ago, over four days when the weather had to be just right all around the world. Completing the image was an enormous undertaking, involving an international team of scientists, supercomputers and hundreds of terabytes of data.

When scientists initially put all that data into the first picture, what they saw looked so much like what they expected they didn't believe it at first.

"We've been hunting this for a long time," Dempsey said. "We've been getting closer and closer with better technology."