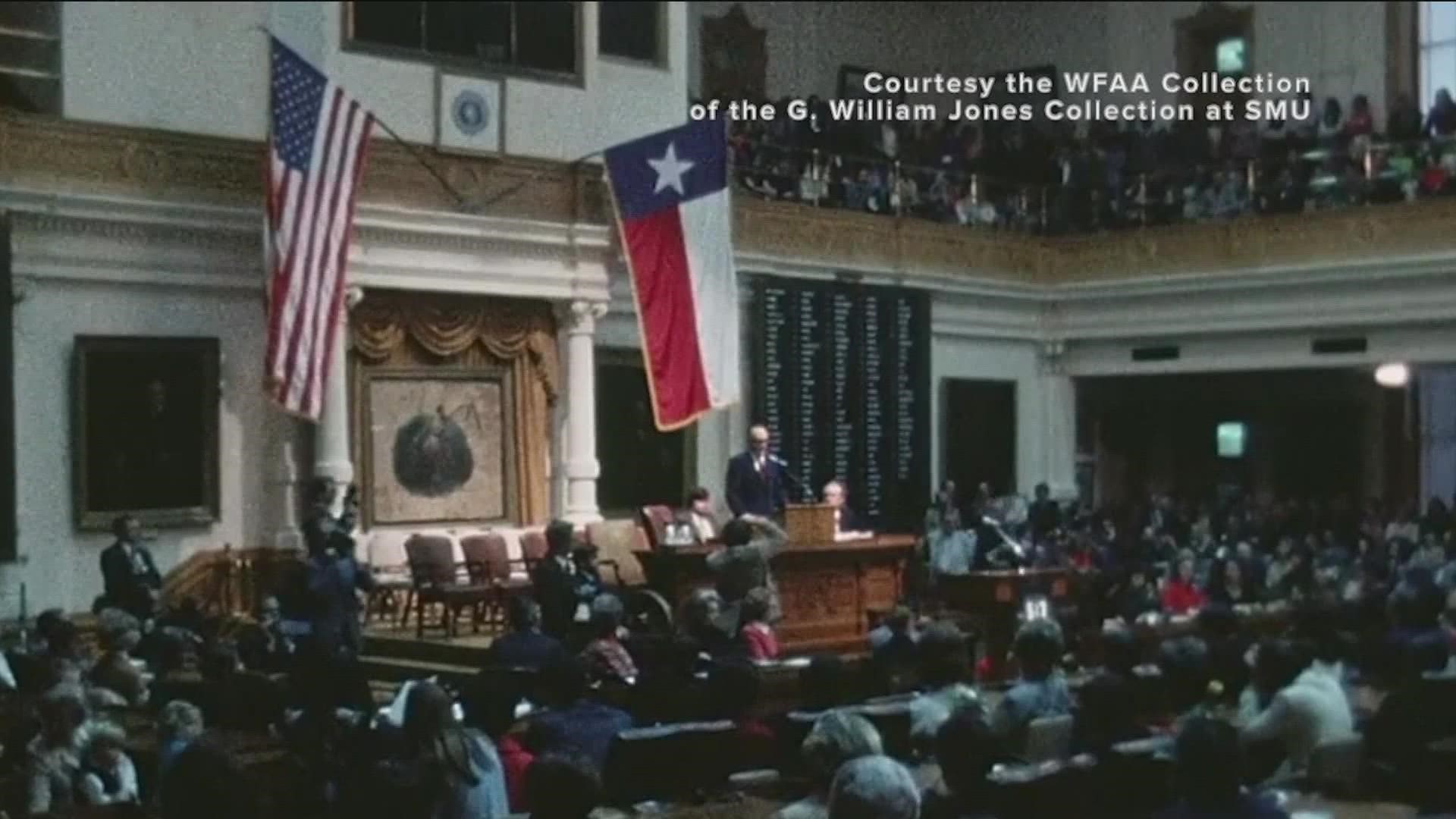

AUSTIN, Texas — It was a classic Texas showdown in 1971. On one side was the powerful speaker of the Texas House, Gus Mutscher (D-Brenham). On the other, 30 members of the Texas House of Representatives unofficially led by State Rep. Frances “Sissy” Farenthold (D-Corpus Christi).

The “30” was made up of a coalition of reformers: Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, who didn’t like the way legislation was handled under Mutscher’s leadership.

They called Mutscher a dictator. But a lobbyist who was a friend of the speaker coined the name for Mutscher’s opponents: “The Dirty 30.” It wasn’t meant as a compliment.

Those 30 lawmakers had also grown concerned that Mutscher was the target of a bribery investigation that involved the Sharpstown Bank of Houston, which had given stock certificates in the bank to Mutscher and others after Sharpstown got favorable legislation approved under Mutscher’s guidance. The fallout was known as the "Sharpstown Scandal."

The “Dirty 30” wanted Mutscher to resign, but he refused. Mutscher retaliated by blocking most of the legislation that the “30” had introduced.

But in September 1971 at the Travis County Courthouse, a bombshell dropped. A grand jury indicted Mutscher and others on a charge of bribery and conspiracy.

The trial was moved from Austin to Abilene and, after 14 days of testimony, the jury found them guilty. Mutscher and the other defendants received five years of probation. The former House speaker was later cleared on appeal.

But the scandal and the work of the “30” led to reform at the Texas State Capitol. Today, lawmakers hold open meetings and operate under a Public Information Act – changes that might not have happened had it not been for the “Dirty 30.”