AUSTIN, Texas — Sex trafficking continues to grow in Texas, but the way we pay to save people caught in the web may be broken.

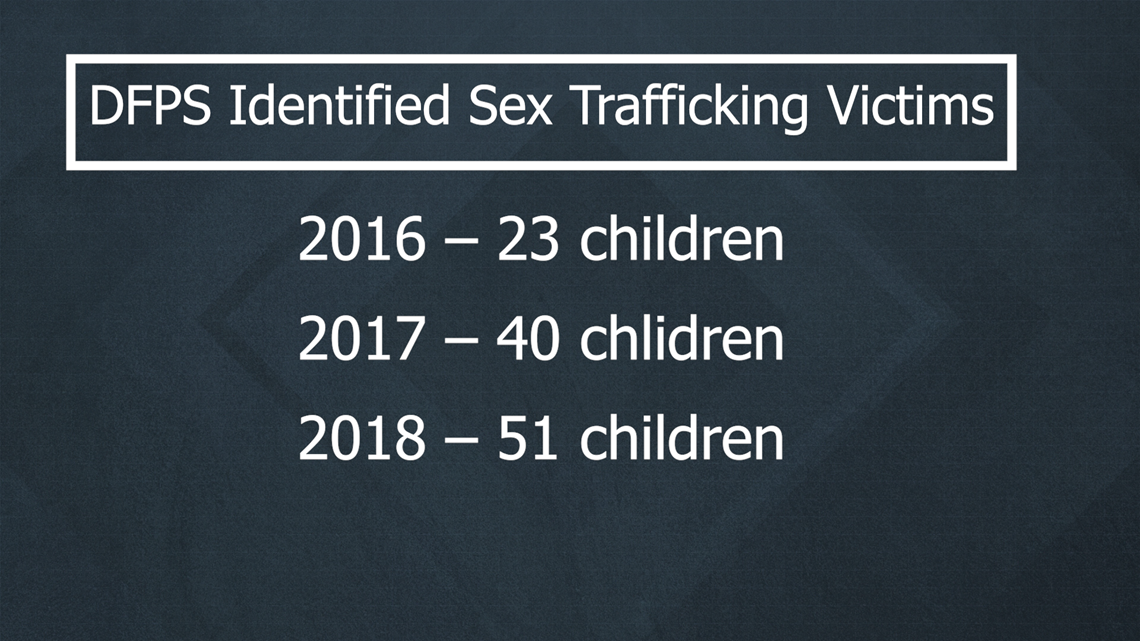

“We’ve found that approximately 50 to 60 children are in fact victims of trafficking,” said Blanca Denise Lance, director of the human trafficking and child exploitation division at the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS).

Lance leads the human trafficking efforts for DFPS, which includes Child Protective Services.

“One of the things that we do is we have the responsibility jurisdictionally (sic) -- we are able to investigate cases of familial trafficking. This is when human trafficking is happening within a family setting usually perpetrated by someone who is traditionally a caregiver of a child in their household,” said Lance.

Tony McKinley, a child sex trafficking survivor, spoke with the KVUE Defenders in 2017.

“You just feel stuck as a kid," McKinley said. "You don't know how to get your way out of it."

She now works with the state, helping youth who are trafficking victims.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton each launched initiatives to combat trafficking.

Those initiatives provide grants such as the one paying Lance’s salary.

“Children who have been exploited are — either labor or sex — are not readily disclosing their own victimization, and so there is a lot of work that has to be done within the community across the nation on recognizing it as a victimization status,” said Lance.

It’s that silence that makes it hard to treat a victim.

LURED BY THE PROMISE OF FAME AND GLAMOUR: A SEX TRAFFICKING VICTIM'S STORY

“It was (my trafficker’s) dream to build his own record label,” said Kathy McGibbon, sex-trafficking survivor in Houston.

“I started to fall in love with the lifestyle, first more than anything. Being invited to the VIP parties and backstage and concerts,” said McGibbon.

KVUE is withholding her trafficker's name because he is not convicted of any crimes.

“He used words like 'us' and 'we' and 'our future', so I really believed that he had my best interest at heart,” said McGibbon.

McGibbon said she grew up in a supportive family, made good grades and attended college and church. She said she and her trafficker dated for a year. Then, he asked her to move.

“He said he needed to go to Dallas for about three months because he had some investors there,” said McGibbon. “But when we got to Dallas he just turned into a different person.”

McGibbon said she was taken to a store to buy risqué clothes and coerced into taking pictures to lure clients.

“I was just hoping he would make the money for the record label — to get the focus, get the picture, keep the picture,” said McGibbon. “I remember it was all a blur, men coming in and out of the room. I remember him saying, ‘Hey, this is just temporary. I’m keeping you safe and I’ll never put you on the street ... I still felt like I was special to him for some reason, until he came to me and said we’re not making the money fast enough and that I was going to go on the street — the very thing that he said that he would never do.”

McGibbon said she and other girls slept for an hour or two between clients. They were given ecstacy (MDMA) to stay alert.

McGibbon said fear kept her trapped.

“I knew the power he had. He took a year to learn where my family lived, the people that meant most to me -- my friends, my church. He knew every detail of my entire life,” said McGibbon.

She said she was beaten when she didn’t make enough money. She trained other women how to sell themselves on the streets.

Then, McGibbon said a miracle happened.

“It was by the grace of God. The young lady that groomed and trained me while we were out there. She had a mental illness and she got really sick. She had a mental breakdown while we were out there. To the point that he couldn’t handle her,” said McGibbon.

She said she convinced her trafficker to bring them back to Houston to get treatment.

In Houston, reality hit McGibbon. She said she also panicked.

“I lost total track of time, because there you don’t pay attention to time. In that life you don’t pay attention to time and all that stuff, it’s just money, money, money —go," said McGibbon. "I think I had a mental block to keep me safe from reality, and that’s how I survived it. I just acted like it was all a dream and it was just going to be over and we were all going to be fine."

McGibbon thought she was away for three months. She learned she was gone for nine months.

“I started having an anxiety attack … I convinced him to call someone for help. That moment turned into freedom for me,” said McGibbon.

She went to her brother's and eventually gained enough courage to cut communication with her trafficker.

Shamed, she lived in silence about what happened for seven years.

“Rescue is a process. So, I had to come to terms first with (the notion) that I wasn’t to blame,” said McGibbon.

McGibbon is building a trafficking case against the man she said enslaved her.

WHY VICTIM REHAB MUST BE A PRIORITY

In KVUE's special report, “Selling Girls,” we told you how sex traffickers in Austin often get away with the crime.

“A lot of times they won’t tell us the whole story,” said Abbey Fowler, Travis County assistant district attorney in 2017.

Survivors become re-victimized in court. Their crimes, committed under someone else’s control, are often used against them.

“Unfortunately, because of that history though, some people look at that them not as victims, but as willing participants,” Fowler said.

Prosecutors, counselors and survivors all told us this: Rehabilitation for the victim must happen before prosecutors can build a case.

“The detectives have been working really hard at trying to form relationships and really making sure that they can build a trust, so slowly, they can find out what's been happening,” Fowler said.

HOW TEXAS CARES FOR SEX TRAFFICKED CHILDREN

“There’s reluctance to identifying themselves as victims. We professionals may be able to see it faster than the actual victim depending on the length of time of the situation; it may be a long treatment plan for a child or an adult depending who it was that was victimized,” said Lance.

The way the state pays for long-term residential treatment may not be structured to give the best care for human trafficking victims.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) developed payment rates for residential child care. Designed for foster care, these are the same levels used for long-term residential care for child trafficking victims.

Any child victim of human trafficking is automatically given a service level of “Intense Plus,” paying providers $400.72 per day for specific, individualized care.

It’s enough money to cover services, but it’s temporary.

The payment decreases once a third party, Youth for Tomorrow, determines the child’s well-being requires less treatment.

But counselors and survivors who spoke with the KVUE Defenders said the levels decrease too quickly.

“Everything is stripped away from you when you’re trafficked,” said McGibbon, the sex trafficking survivor.

Note on graphic above: This is for familial trafficking and does not include runaways.

While McGibbon stayed silent about what happened for seven years, rehabilitation took another two.

“Rescue is not an event. It’s a process,” said McGibbon.

Why the state doesn’t guarantee children long-term residential treatment, is a catch-22.

DFPS needs “empirical evidence”: evidence based on observation or experience.

But to get that “observation or experience,” someone must pay.

“It’s a specialty. We’re learning in how this plays out, what the long-term effects are, how long and what the right treatment plans are,” said Lance.

Which will take time.

Time victims don’t have.

AUSTIN-AREA CHARITY AIMS TO BE A MODEL FOR LONG-TERM RECOVERY SERVICES

“It’s an epidemic,” said Brooke Crowder, founder and CEO of The Refuge for Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking (DMST).

The charity houses and rehabilitates girls 11- to 19-years-old. The children are referred to them by governmental bodies such as certain juvenile courts, and by the community. It’s the largest residential treatment facility in the country with housing available for up to 48 girls.

“We did start receiving girls in August and have been adding girls ever since. Usually one or two a month and now it’s escalating to like one a week,” said Crowder.

The Refuge for DMST currently has a contract with DFPS for $127,750. It was signed to pay for one girl, who therapists said needs treatment for at least two years. But the contract expires October 2019. The Refuge for DMST will use donated money to pay for the remaining therapy.

PHOTOS: A 'refuge' for child sex trafficking victims in Austin

Crowder is in negotiations with DFPS for funding for ensure long-term specialized care.

Meanwhile, they rely on community donations and work with researchers at the University of Texas to study the impact of long-term specialized residential care.

“Until we are able to get the right kind of funding from the state, we have gaps,” said Crowder. “It’s hard to place a dollar amount on recovery.”

Crowder said The Refuge will never discharge or transfer a child due to a lack of state funding.

"We are getting calls from all over the U.S., and we're looking at other sources for placement, including federal placements. To benefit these children, we really want to work with child-centric entities," said Crowder.

HOW TEXAS LAWMAKERS HAVE -- AND HAVEN'T -- OFFERED HELP

So, the challenge to pay for services falls on lawmakers, who are in legislative session.

At a rally in January, people on both sides of the aisle agreed to help tackle human trafficking issues this year.

“We need monies for mental health. We need monies for housing. They need a multitude of services and until we are able to provide those services. We’re not really doing much to scratch the surface there,” said Texas Rep. Senfronia Thompson, District 141.

Rep. Thompson authored three bills so far, HB403, HB292, and HB1216. None includes rehabilitation services.

“This is a battle. This is a war and it does take the legislature,” said Texas Sen. Joan Huffman, District 17.

“The reality is this is a mark of shame on our state,” said Texas Rep. Tan Parker, District 63.

Parker has not authored any bills relating to human trafficking yet, but his office told the KVUE Defenders he is working on a non-disclosure bill which would allow victims to seal their criminal records incurred while being trafficked.

A similar bill is already filed in the Texas House by Rep. Thompson.

“We are going to shut this thing down in the state of Texas,” said Texas Rep. Matt Shaheen, District 66.

Rep. Shaheen authors one bill, HB934, relating to the prosecution of trafficking. He has filed nothing for rehabilitation services.

So far, Texas lawmakers have 25 bills filed regarding trafficking. Three —HB1113, HB 1698 and SB 781 — are designed to improve services for sex trafficking victims.

HB 1113, authored by Rep. Sarah Davis, District 134, creates a treatment program for sex trafficking prevention and rehabilitation.

HB 1698, authored by Rep. Ben Leman, District 13, creates a quality-based payment system to “promote the provision of high-quality services by residential treatment centers.”

SB 781, authored by Sen. Lois Kolkhorst, District 18, is identical to HB 1698, also creating a quality-based payment system.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: