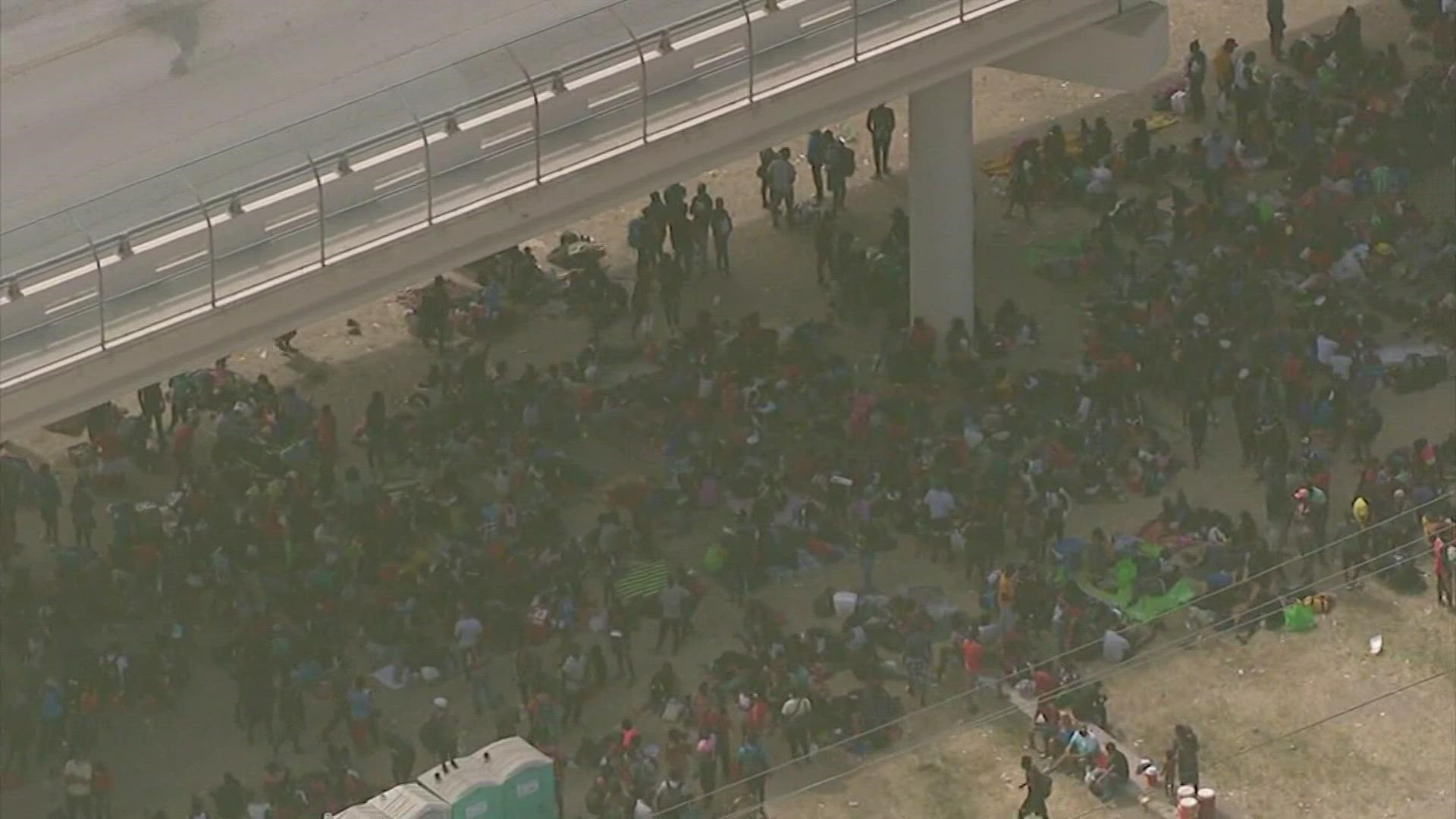

DEL RIO, Texas — Thousands of Haitian migrants assembled under and around a bridge in a small Texas border town as chaos unfolded Friday, presenting the Biden administration with a new challenge as it tries to manage large numbers of asylum-seekers who have been reaching U.S. soil.

Haitians crossed the Rio Grande freely and in a steady stream, going back and forth between the U.S. and Mexico through knee-deep water with some parents carrying small children on their shoulders. Unable to buy supplies in the U.S., they returned briefly to Mexico for food and cardboard to settle, temporarily at least, under or near the bridge in Del Rio, a city of 35,000 that has been severely strained by migrant flows in recent months.

Migrants pitched tents and built makeshift shelters from giant reeds known as carrizo cane. Many bathed and washed clothing in the river.

The vast majority of the migrants at the bridge on Friday were Haitian, said Val Verde County Judge Lewis Owens, who is the county's top elected official and whose jurisdiction includes Del Rio. Some families have been under the bridge for as long as six days.

Trash piles were 10 feet wide, and at least two women have given birth, including one who tested positive for COVID-19 after being taken to a hospital, Owens said.

Val Verde County Sheriff Frank Joe Martinez estimated the crowd at 13,700 and said more Haitians were traveling through Mexico by bus.

About 500 Haitians were ordered off buses by Mexican immigration authorities in the state of Tamaulipas, about 120 miles south of the Texas border, the state government said in a press release Friday. They continued toward the border on foot.

Haitians have been migrating to the U.S. in large numbers from South America for several years, many of them having left the Caribbean nation after a devastating earthquake in 2010. After jobs dried up from the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, many made the dangerous trek by foot, bus and car to the U.S. border, including through the infamous Darien Gap, a Panamanian jungle.

It is unclear how such a large number amassed so quickly, though many Haitians have been assembling in camps on the Mexican side of the border, including in Tijuana, across from San Diego, to wait while deciding whether to attempt to enter the United States.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment. “We will address it accordingly,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said on MSNBC.

The Federal Aviation Administration, acting on a Border Patrol request, restricted drone flights around the bridge until Sept. 30, generally barring operations at or below 1,000 feet unless for security or law enforcement purposes.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican and frequent critic of President Joe Biden, said federal officials told him migrants under the bridge would be moved by the Defense Department to Arizona, California and elsewhere on the Texas border.

Some Haitians at the camp have lived in Mexican cities on the U.S. border for some time, moving often between them, while others arrived recently after being stuck near Mexico's southern border with Guatemala, said Nicole Phillips, the legal director for advocacy group Haitian Bridge Alliance. A sense of desperation spread after the Biden administration ended its practice of admitting asylum-seeking migrants daily who were deemed especially vulnerable.

“People are panicking on how they seek refuge,” Phillips said.

Edgar Rodríguez, lawyer for the Casa del Migrante migrant shelter in Piedras Negras, north of Del Rio, noticed an increase of Haitians in the area two or three weeks ago and believes that misinformation may have played a part. Migrants often make decisions on false rumors that policies are about to change and that enforcement policies vary by city.

U.S. authorities are being severely tested after Biden quickly dismantled Trump administration policies that Biden considered cruel or inhumane, most notably one requiring asylum-seekers to remain in Mexico while waiting for U.S. immigration court hearings. Such migrants have been exposed to extreme violence in Mexico and faced extraordinary difficulty in finding attorneys.

The U.S Supreme Court last month let stand a judge's order to reinstate the policy, though Mexico must agree to its terms. The Justice Department said in a court filing this week that discussions with the Mexican government were ongoing.

A pandemic-related order to immediately expel migrants without giving them the opportunity to seek asylum that was introduced in March 2020 remains in effect, but unaccompanied children and many families have been exempt. During his first month in office, Biden chose to exempt children traveling alone on humanitarian grounds.

The U.S. government has been unable to expel many Central American families because Mexican authorities have largely refused to accept them in the state of Tamaulipas, which is across from Texas' Rio Grande Valley, the busiest corridor for illegal crossings. On Friday, the administration said it would appeal a judge's ruling a day earlier that blocked it from applying Title 42, as the pandemic-related authority is known, to any families.

Mexico has agreed to take expelled families only from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, creating an opening for Haitians and other nationalities because the U.S. lacks the resources to detain and quickly expel them on flights to their homelands.

In August, U.S. authorities stopped migrants nearly 209,000 times at the border, which was close to a 20-year high even though many of the stops involved repeat crossers because there are no legal consequences for being expelled under Title 42 authority.

People crossing in families were stopped 86,487 times in August, but fewer than one out of every five of those encounters resulted in expulsion under Title 42. The rest were processed under immigration laws, which typically means they were released with a court date or a notice to report to immigration authorities.

U.S. authorities stopped Haitians 7,580 times in August, a figure that has increased every month since August 2020, when they stopped only 55. There have also been major increases of Ecuadorians, Venezuelans and other nationalities outside the traditional sending countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

___

Spagat reported from San Diego. Associated Press writers Paul Weber in Austin, Ben Fox in Washington, David Koenig in Dallas and Maria Verza in Mexico City contributed to this report.

Some Haitians at the camp have lived in Mexican cities on the U.S. border for some time, moving often between them, while others arrived recently after being stuck near Mexico's southern border with Guatemala, said Nicole Phillips, the legal director for advocacy group Haitian Bridge Alliance. A sense of desperation spread after the Biden administration ended its practice of admitting asylum-seeking migrants daily who were deemed especially vulnerable.

“People are panicking on how they seek refuge,” Phillips said.

Edgar Rodríguez, lawyer for the Casa del Migrante migrant shelter in Piedras Negras, north of Del Rio, noticed an increase of Haitians in the area two or three weeks ago and believes that misinformation may have played a part. Migrants often make decisions on false rumors that policies are about to change and that enforcement policies vary by city.

U.S. authorities are being severely tested after President Joe Biden quickly dismantled Trump administration policies that Biden considered cruel or inhumane, most notably one requiring asylum-seekers to remain in Mexico while waiting for U.S. immigration court hearings. Such migrants have been exposed to extreme violence in Mexico and faced extraordinary difficulty in finding attorneys.

The U.S Supreme Court last month let stand a judge's order to reinstate the policy, though Mexico must agree to its terms. The Justice Department said in a court filing this week that discussions with the Mexican government were ongoing.

A pandemic-related order to immediately expel migrants without giving them the opportunity to seek asylum that was introduced in March 2020 remains in effect, but unaccompanied children and many families have been exempt. During his first month in office, Biden chose to exempt children traveling alone on humanitarian grounds.

The U.S. government has been unable to expel many Central American families because Mexican authorities have largely refused to accept them in the state of Tamaulipas, which is across from Texas' Rio Grande Valley, the busiest corridor for illegal crossings. On Thursday, a federal judge in Washington blocked the administration from applying Title 42, as the pandemic-related authority is known, to any families.

Mexico has agreed to take expelled families only from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, creating an opening for Haitians and other nationalities because the U.S. lacks the resources to detain and quickly expel them on flights to their homelands.

In August, U.S. authorities stopped migrants nearly 209,000 times at the border, which was close to a 20-year high even though many of the stops involved repeat crossers because there are no legal consequences for being expelled under Title 42 authority.

People crossing in families were stopped 86,487 times in August, but fewer than one out of every five of those encounters resulted in expulsion under Title 42. The rest were processed under immigration laws, which typically means they were released with a court date or a notice to report to immigration authorities.

U.S. authorities stopped Haitians 7,580 times in August, a figure that has increased every month since August 2020, when they stopped only 55. There have also been major increases of Ecuadorians, Venezuelans and other nationalities outside the traditional sending countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

___

Spagat reported from San Diego. Associated Press writers Paul Weber in Austin, Ben Fox in Washington and Maria Verza in Mexico City contributed to this report.