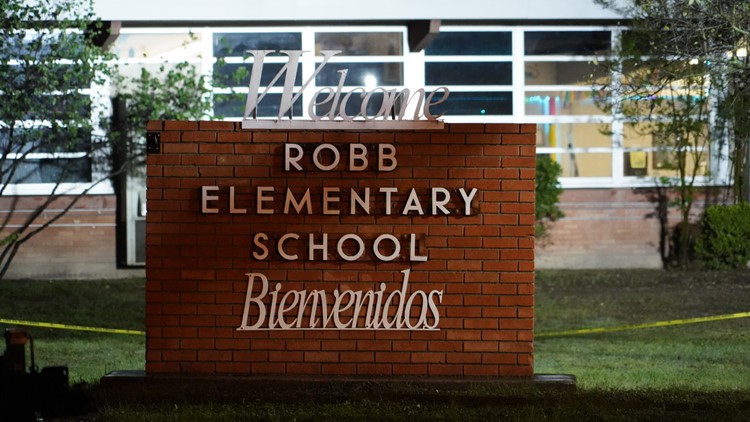

THE TEXAS TRIBUNE – After more than a year of pressure to file criminal charges against some of the Texas law enforcement officers responsible for the botched response to the Robb Elementary School shooting, local prosecutor Christina Mitchell last month convened a grand jury to investigate.

But even after that monthslong review is complete, law enforcement officers may not face criminal charges, legal experts say. That’s because police officers are almost never criminally prosecuted — and charges for failing to act are even more rare.

Grand jury proceedings in Texas are kept secret and it’s not typically known how cases are presented to jurors who decide whether there’s enough evidence to formally charge someone with a crime or proceed to a trial.

It’s unclear whether Uvalde’s District Attorney plans to present evidence to grand jurors that some victims would have survived had medical responders started treatment earlier. Hundreds of officers who responded to the shooting waited 77 minutes to breach the classrooms, where a gunman used an AR-15 rifle to indiscriminately shoot students and teachers in two adjoining fourth-grade classrooms. Nineteen students and two teachers died in the May 24, 2022 shooting.

The Texas Rangers in August 2022 asked Dr. Mark Escott, medical director for Texas Department of Public Safety and chief medical officer for the city of Austin, to look into the injuries of the victims and determine whether any victims could have survived. Four of the victims are known to have had heartbeats when they were rescued from the classrooms.

But one year later, Mitchell’s office told Escott it was “moving in a different direction” and no longer wanted the analysis to be performed.

“It’s unclear to me why they would not want an analysis such as this done,” Escott said.

Escott said he was never given access to the autopsy reports or hospital and EMS records. Based on the limited records he did review, he believes at least one individual may have survived had police officers intervened earlier.

U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland visited Uvalde last month to present findings from a scathing 575-page federal report. He said lives could have been saved if officers had confronted the shooter earlier, instead of ignoring established mass shooting protocols.

The DOJ report also noted that at least one deceased victim was alive at 11:56 a.m., 20 minutes after officers entered the school.

Mitchell has not responded to The Tribune’s multiple requests for comment. It therefore remains unclear why she halted the survivability study, which could have provided critical information to the grand jury.

State Sen. Roland Gutierrez, D-San Antonio, said the Uvalde families deserve accountability and clarity on victims’ survivability.

“That they halted the study is very disturbing to me,” Gutierrez said. “It seems to me that there is some unwillingness to tell the truth.”

Gutierrez called the shooting response “the worst law enforcement response in the history of the United States” and said he believes victims could have survived had police acted more quickly.

A DUTY TO PROTECT

Even though police training instructs officers to confront a shooter, hundreds of officers responding to Robb Elementary waited over an hour to confront the gunman

The U.S. Supreme Court has consistently held that officers do not have a constitutional “duty to protect,” even if they have been trained to do so. And even if the Uvalde grand jury decides to indict officers, prosecutors would then have the difficult burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the officers were under a specific legal duty to act and that in failing to act they caused a specific harm.

“There’s a big difference between what is morally right and what the law actually requires,” said Seth Stoughton, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law and former police officer. “I’d be very surprised if there was a straightforward path to criminal prosecution.”

The U.S. Justice Department’s report found failures in leadership, command and coordination at the scene of the shooting. The biggest error, the report stated, was that officers wrongly treated the situation as a barricaded subject incident instead of an active shooter, despite evidence to the contrary.

Several officers resigned or were fired in the months following the shooting. Pete Arredondo, former chief of the school district’s police department, was fired by the school board in August 2022. He was one of a handful of officers named in the DOJ report.

Kirk Burkhalter, a professor of law at New York Law School, said he suspects that law enforcement officers could face three possible criminal charges: manslaughter, criminally negligent homicide, and abandoning or endangering a child.

Those first two charges would require the prosecution to prove that the officers “caused the death of” an individual. Evidence that any victims may have survived the attack had officers intervened more quickly could support the charge. It’s not clear if Mitchell’s office had someone pursue such evidence after scrapping the survivability report.”

Similar studies have been done following other mass shootings, such as the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando. In that study, researchers reported that 16 of the 49 victims had potentially survivable wounds had they received faster medical care and made it to a hospital within an hour. Still, the officers who responded to the Pulse shooting in 2016 weren’t criminally charged.

RELATED: Uvalde grand jury to examine if law enforcement could face charges for Robb Elementary mass shooting

Even if the prosecution could prove victims would have survived with a faster police response, they will also have to demonstrate that the officers acted either “recklessly” or “negligently” through their inaction.

Lawyers said they are not aware of previous cases where police officers have been successfully prosecuted for failing to act.

Last year, a jury acquitted a former school resource officer who stayed outside during the February 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The officer faced seven counts of felony child neglect, three counts of culpable negligence and one count of perjury. The state’s argument that the officer had a duty to protect students failed to win favor among the jury.

Some legal experts speculated that community pressure played a role in the convening of a grand jury in Uvalde.

“I think the DA may be trying to create some goodwill in the community and maybe address her political concerns for her future,” said G.M. Cox, a former chief of police and lecturer at Sam Houston State University. “The reality is that it’s going to be tough to file a criminal case.”

Disclosure: Sam Houston State University has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune.