When Franklin County rancher Bruce Hunnicutt discovered that the Texas Department of Agriculture had approved the use of the poison warfarin to control feral hogs, he had a lot of questions.

The biggest was: What would happen if someone ate the meat from wild pig that had consumed it?

Hunnicutt, 58, operates a hog hunting business on 30,000 acres — he owns 600 and leases another 24,000 — in Northeast Texas. He regularly sends the meat of the pigs they kill home with his clients.

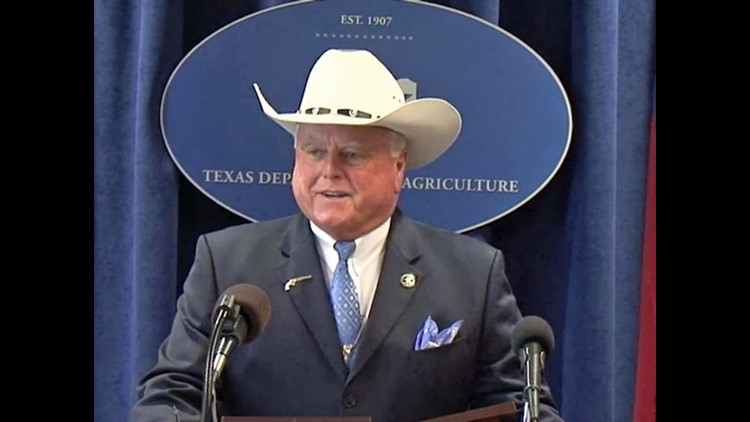

When he couldn’t find answers online, he called the agriculture department to get more information. To his surprise, he got a return call from Commissioner Sid Miller, who assured Hunnicutt the poison would be safe to humans and other wildlife, and directed him to his Facebook page for more information on the poison that’s marketed under the name Kaput.

When Hunnicutt found the product’s label, he was so alarmed he called his state representative.

“That label didn’t look anything like what the man [Miller] told me on the phone —I thought, 'My god, that can’t be right — people can’t eat this,' ” he said. “How in the world can you put something in the human food chain that can kill somebody, to kill an animal that people eat?”

When he traveled to Austin to meet with Rep. Gary VanDeaver, he got the chance to address Miller in person.

In the March 3 meeting set up by VanDeaver’s office, which was recorded with Miller’s permission, the commissioner responded to some of Hunnicutt’s safety concerns by saying that his agency could change the poison’s federally approved label to eliminate an important warning — as well as a requirement to bury the carcasses of poisoned hogs, which Miller said simply wasn’t “doable.”

In the recording, which Hunnicutt provided to The Texas Tribune, Hunnicutt says: “That product label right there says ‘all animals’ … every one of them has to be recovered and put 18 inches under the ground. How you going to do that? … How you going to find all of them, Mr. Miller?”

“I guess we should take that off the label, it’s not doable,” Miller says. “We’ll take it off.”

Hunnicutt then referred to the label's warnings about the dangers of the poison to other wildlife and domesticated animals.

“Animals that feed on those carcasses are going to die. It can kill them,” he told Miller. “Whether you say it or not, the label says it will.”

Miller responded: “We can adjust that too.”

The meeting lasted about 30 minutes, growing increasingly tense, before Miller finally stood up and walked out.

“It’s like he wasn’t listening to me, he had his mind made up, he had his little dog and pony show he’s been putting on this whole time,” Hunnicutt said.

VanDeaver said the meeting was impromptu, and that he understood that Miller may not have been prepared to answer all of Hunnicutt’s questions.

But the New Boston Republican said he was troubled by the suggestion of changing the label and Miller’s indication that some of the poison’s use restrictions were not enforceable.

Miller, a Republican, has publicly championed the poison, which he has called a vital weapon against the state’s population of more than 2 million wild hogs and the damage they do to crops, wildlife and the environment.

For months, the Texas Department of Agriculture has responded to concerns by citizens and businesses that opposed using the warfarin-based poison to control hogs by highlighting a long list of safety requirements: special feeders with weighted lids so other animals couldn’t get to the poisoned feed; carcasses of hogs that consume it had to be buried at least 18 inches underground; warnings on the label against allowing livestock grazing or hunting in areas around baited feeders for at least 90 days after removing the poison.

It is unclear from the recorded conversation whether Miller understood that the label includes federal restrictions for the poison’s use that the Environmental Protection Agency approved in January — or that tampering with the label could be a violation of federal law.

Miller spokesman Mark Loeffler confirmed that the meeting had happened, and that Miller had consented to the recording.

“Mr. Hunnicutt was clearly upset by the feral hog bait issue. Nevertheless, the commissioner stayed cool and made every attempt to answer the gentleman’s questions in a professional manner,” he said in a statement.

Loeffler said Miller had “transposed the term ‘label’ and ‘rule’ in attempting to answer Mr. Hunnicut’s very emotional line of questioning.”

When the EPA approves a pesticide, its manufacturer must then apply for registration at the state level. States then have the authority to deny registration or create their own rules for use.

Loeffler said that the state agriculture department could also contact the federal agency with “suggestions or edits” to EPA-approved labels.

Asked whether Miller believes that the restrictions on the poison’s use are unenforceable, as he appeared to suggest in his conversation with Hunnicutt, Loeffler declined to answer the question. Since the bait was no longer registered in Texas, Loeffler said, the point was moot.

Shortly after a bill requiring further study of the hog poison passed the state House of Representatives in late April, Scimetrics, the Colorado-based manufacturer, announced that it had withdrawn its request to operate in Texas, citing the threat of lawsuits.

"Our family-owned company cannot at this time risk the disruption of our business and continue to compete with special interests in Texas that have larger resources to sustain a lengthy legal battle," the company's statement said.

Opponents of the poison fear the move may be an effort to wait out the legislative session, which ends May 29.

The bill has so far stalled in state Sen. Charles Perry’s Agriculture, Water and Rural Affairs committee. It received a hearing there last Monday, but has yet to be called for a vote. Perry, R-Lubbock, did not return a request for comment.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune.

Texas Tribune mission statement

The Texas Tribune is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.