CLEVELAND — The old tree hangs tough -- standing its ground even in the face of whatever nature tosses its way. The sturdy old oak known for strength has lived up to its billing for eighty-four years.

It was not sprouted from an acorn in its Cleveland location, but from one in the sprig hand-carried here by a Clevelander who performed on the world stage of the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

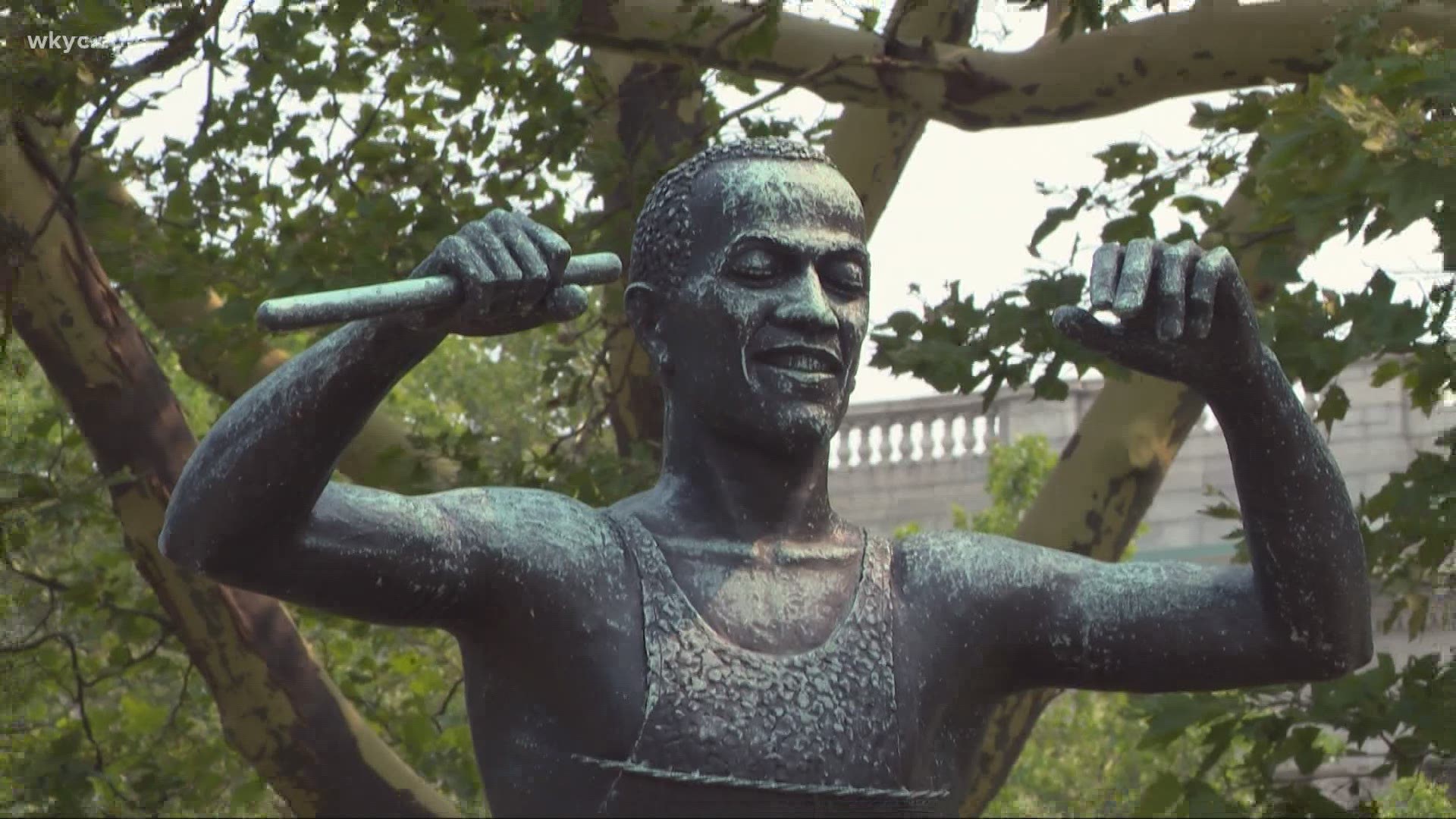

The story of a Cleveland man awarded the tree when it was a sapling and he a sprinter. With four Olympic victories, Jesse Owens brought the trees home to be planted.

Only one remains.

On the Cleveland West Side, the old oak at James Ford Rhodes School track – where Owens often practiced – still grows.

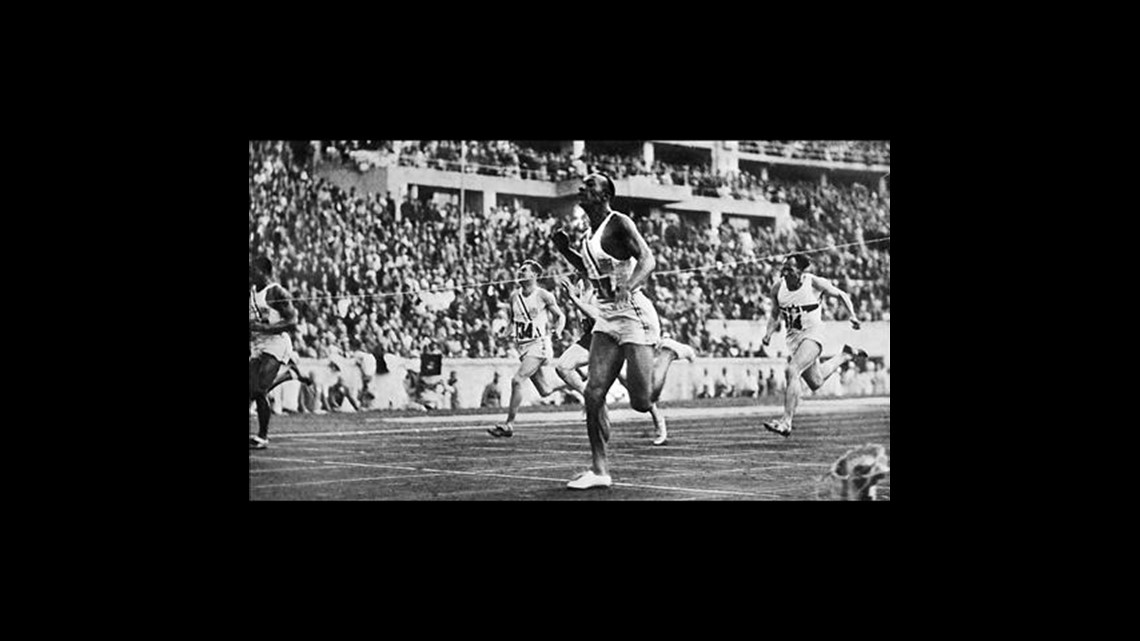

Owens was the champion sprinter from Cleveland East Tech High School and later Ohio State University. He won the 100 meter, 200 meter, one of the relay races, and the long jump at the ‘36 Olympics where he was snubbed by Adolph Hitler, whose myth of Aryan supremacy was destroyed by African American Owens.

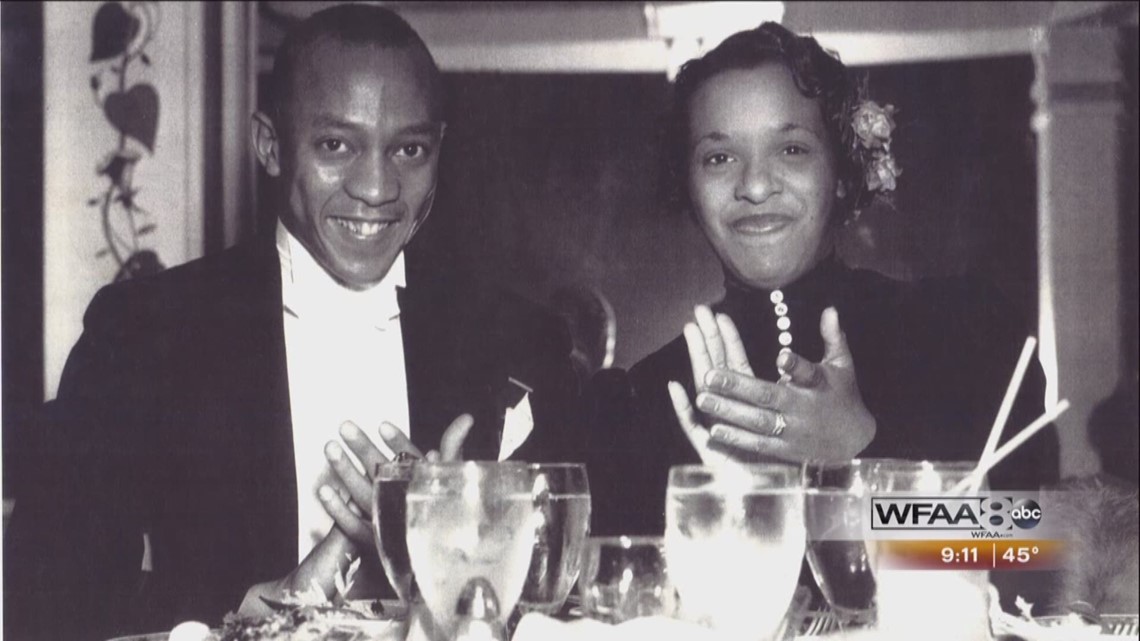

In New York, Owens was welcomed as the Olympic champion. But even back in the United States, the hotel where Owens was honored required him to take a freight elevator to reach the event.

Owens and the other Black American medal-winning Olympians received no invitations to the White House to shake hands with President Franklin Roosevelt. That honor was for white Olympians only.

There was a big parade at home in Cleveland, followed by a job with Cleveland's Parks and Recreation department. Owens began a dry-cleaning business that didn't do well, forcing personal bankruptcy. To make a living, Jesse was forced to put on running exhibitions such as racing a horse.

He needed money.

"I couldn't eat gold medals," he said. This Olympian who was the best in racing on a track could not run from racist ideas.

Six years later, he was given the job of Director of National Fitness for African Americans. He eventually moved into public relations, but that was twenty years after the Olympics.

Long after the Olympics, I met Jesse Owens. I was so young I don't remember. My parents said I looked at him with wide eyes. Of course, later I grew to fully understand his fame. I did know Jesse’s nephews and his brother, who married my cousin. So, Jesse Owens and I were kind of family... sort of.

Throughout his life, he supported this nation and did what he could in the civil rights movement. I think of him like his old oak tree, as strong both physically and in his character.

Recently, a sprig of the surviving original Owens tree was grafted and planted in Rockefeller Park in University Circle. It was as if Jesse had passed a baton to the next branch of family.

This year, I will especially reflect on 1936 when Cleveland's-own won gold for the 100 and 200 meters, relay, and the long jump.

I will think of the house at East 100th Street and Carnegie where Jesse lived, his East Tech High School, and the oak saplings the Olympics awarded him with his gold medals. He died in 1980, but in his life, he ran the good race on and off the track even in the face of racial obstacles. For me, there are memories.

Jesse Owens, striding for America in the Olympics. There is something golden in what he achieved-- especially at the time he did it.

MORE OLYMPICS COVERAGE:

- RELATED: How to watch the Tokyo Olympics Opening Ceremony

- RELATED: Tokyo Olympics COVID cases reach 91 as 2 more athletes test positive

- RELATED: Suni Lee’s road to Olympics paved with sacrifice and tragedy

- RELATED: VERIFY: No, Olympic athletes are not required to get vaccinated before the Olympic Games

Editor's note: The video in the player above is from an unrelated story, published on July 21, 2021.