AUSTIN, Texas — "They told me that if I continue to protest or march, their words were, 'We will make you disappear," Reynaldo Serra said.

Serra loved where he grew up in Venezuela, but he said he could not stay there.

He was beaten and jailed for protesting against the Venezuelan government. He said a group of Venezuelan government contract workers also threatened his daughter.

Venezuela is dangerous, according to the U.S. Department of State. Travel advisories state that Americans should stay out of the country. A recent United Nations resolution shows human rights violations, extrajudicial killings and a concern for the lives of those sent back to Venezuela.

"I had to leave my country. I was very afraid there. I was very afraid, afraid something would happen to me," Serra said.

The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website shows, "You may apply for asylum if you are at a port of entry or in the United States."

Serra went to an international bridge in Laredo, Texas. There, he said he asked for asylum. He said he was told to stay in Mexico and wait for a court hearing.

"I cried every day," Serra said.

He joined 70,000 other asylum seekers forced to wait across the border.

Crowded shelters in Mexico took in families and children who were alone. But Serra said he couldn’t find any shelters.

He ended up cleaning a school's pool. He slept in the janitor’s closet.

"It was hard," Serra said.

Months passed. Then Serra heard about a group of attorneys who help migrants waiting in Mexico.

Now Dicky Grigg, a personal injury attorney, helps Serra for free.

"You're making a difference in somebody's life," Grigg said.

"My guardian angel was born," Serra said.

Grigg does not have a history of working immigration court claims, and he does not speak Spanish. So Grigg offers his help through a nonprofit called VECINA.

The organization was founded to help recruit attorneys like Grigg. The volunteers pair recruiters with pro-bono immigration attorneys and translators.

"It takes that work off of the shoulders of the on-the-ground legal services providers and says, 'We'll take these cases,'" said Kate Lincoln-Goldfinch, an Austin-based immigration attorney and the president of VECINA's board of directors.

Lincoln-Goldfinch said VECINA has a lot of work ahead of it.

In 2019, then-President Donald Trump created the Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP). It’s known as the "Remain in Mexico" policy. MPP ordered those seeking asylum to stay outside the U.S. border as they await court hearings.

President Joe Biden ended the program and allowed migrants to cross into the U.S. A temporary shelter in Donna, Texas, houses migrants until they can be placed elsewhere.

Unaccompanied children are turned over to Health and Human Services. Adults and families may go into Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody as they work their asylum claims.

"Taking an immigration case, especially an asylum case, can be really daunting for someone," Lincoln-Goldfinch said.

She said MPP case backlogs and COVID-19 shutdowns may delay an asylum case for years.

"It's like you literally have someone's life in your hands," Lincoln-Goldfinch said.

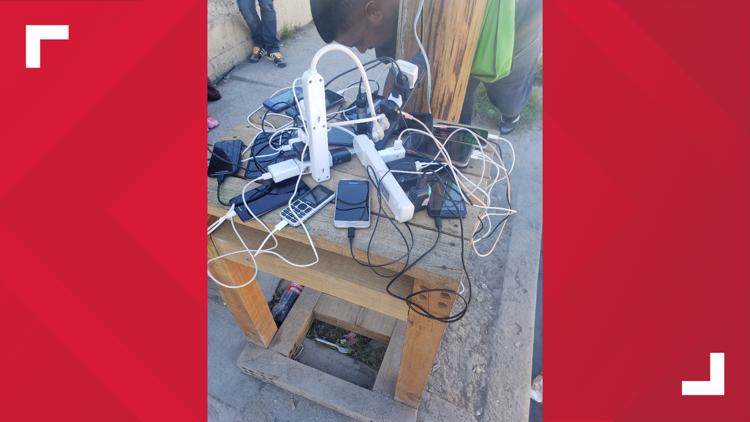

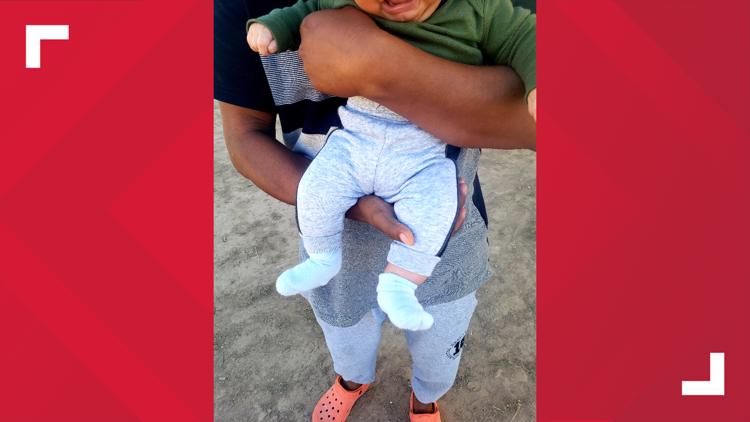

PHOTOS: Conditions at the border as seen by an immigration attorney

VECINA started with helping adult asylum claims. Once MPP ended, they also focused on migrant children’s rights.

"What's supposed to happen under the Flores Settlement is that if a child is apprehended or if they come to the bridge, then within three days, they should be transferred into the Office of Refugee Resettlement," Lincoln-Goldfinch said.

The Refugee Act of 1980 established the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). The government agency works with private companies and nonprofits.

The Texas Tribune and the Center for Investigative Reporting show more than two dozen ORR shelters in Texas. The shelters house migrant children until caseworkers can place the children with family members or in foster homes.

Lincoln-Goldfinch said the process should work quickly but it doesn’t.

"The system has atrophied because everything was shut down," Lincoln-Goldfinch said.

In April, the average stay for an unaccompanied child in U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) custody had plummeted to about 20 hours, below the legal limit of 72 hours and down from 133 hours in late March.

Lincoln-Goldfinch said part of the delay was due to the migrant childrens’ shelters being closed.

"The facilities have to be reopened. They have to be staffed. Caseworkers have to be assigned to these kids. And so, the resulting chaos is a natural consequence of having shut off the system," Lincoln-Goldfinch said.

Lincoln-Goldfinch said migrant child center closures go back to January 2019. The MPP policy included children.

Then the pandemic hit.

The Department of Justice reviewed how the government handled immigration court cases. The active migrant shelters closed to outsiders. Pro-bono attorneys were kept out, the review showed. Immigration courts stopped hearing certain cases, including those remaining in Mexico.

"They may have been out of sight, out of mind for many of us, but they've been in danger this entire time," Lincoln-Goldfinch said.

When the courts could resume all cases in June 2020, federal investigators noted in the Pandemic Response Report, "many immigration courts were still not holding non-detained hearings."

Those under MPP did not have cases resume immediately. Analysis from Syracuse University’s TRAC Reports shows 85% of MPP cases have not been transferred to immigration court.

The latest government statistics show most children and adults are still turned away at the border due to the COVID-19 threat.

Under Title 42, CBP prohibits, "the entry of certain persons who potentially pose a health risk, either by virtue of being subject to previously announced travel restrictions or because they unlawfully entered the country to bypass health screening measures," the CBP’s website shows.

Translation errors on Serra’s paperwork could have put his case in jeopardy, but Grigg and his team caught it.

"Everything was wrong. So, if it wasn’t for them..." Serra said.

As the nation moves beyond the pandemic, Lincoln-Goldfinch said more attorneys need to work together to help reduce the immigration backlog and help those waiting for legal migration.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING:

- Texans get millions of robocalls every day, per national data

- Austin's housing boom pushes people to buy Hill Country land at record pace

- Monica's Law: How a tragedy changed the protective order search process in Texas

- A Texas soldier reported sexual harassment. Then, she became the subject of a potentially career-ending investigation

- Defenders: Why Central Texas development may be partly to blame for toxic blue-green algae