AUSTIN — Editor's note: In light of the deaths of George Floyd, Austin's Mike Ramos and others, KVUE is recirculating this 2018 piece which highlights Austin's history with gentrification.

The City of Austin is often seen as one of the best places to live.

With a thriving tech industry, enviable landscape and crowd-pleasing amenities, it's where locals like to keep things weird and where live music lives. But there's a less appealing phenomenon happening in Austin. Mayor Steve Adler described it in a news conference in February.

"We are losing people and we are losing communities," Adler said.

Decreasing diversity and economic segregation are the side effects of Austin's affordability crisis; fueled by gentrification. While it may seem this problem is getting worse, it's certainly not new.

"The gentrification, the displacement -- all of these things are legacies that were orchestrated from the 1928 plan," said Stephanie Lang, a community curator.

Lang is a fifth generation Austinite who's working to preserve the history of Austin's black communities. Her latest project, "Seen and Unseen: A Sunday Afternoon in Clarksville," is housed in the John L. Warfield Center at the University of Texas at Austin. She's also training students to give walking tours of Clarksville, one of Austin's freedmen communities. She took KVUE's Ashley Goudeau on a tour.

"A lot of the houses that were built in these freedman communities look very much like the slave cabins," Land said. "Which would make sense because that's what they knew."

Clarksville is named after freed slave Charles Clark.

"He bought up a plot of land and divvied it up -- pieces up -- and sold it and that's kind of how the community started," Lang added.

Unlike other cities, Austin's 15 freedman communities were spread out all over the city. This attracted freed slaves to Austin.

"They felt because of the way Austin was set up versus a lot of other towns, Austin was more condense. And so they felt like they had a police presence so they could feel safer and more protected. You know there was certain work that they would do that would be considered like in the hub of the city," Lang said.

But a lot of that changed with the City Plan of 1928. Consulting engineers devised a land development plan for the city. They noticed black people were living "in practically all sections of the city" on land that was "valuable." And in a time when separate but equal was the law of the land, this presented a "race segregation problem." So the engineers suggested all facilities for black people -- including schools and parks -- be located in a "Negro District" to eliminate duplicating services.

The consultants recommended creating the district east of East Avenue, which is now Interstate 35. They chose this area because the population there seemed to be all black and the "value of the land was very low."

"It wasn't like an automatic thing like, 'OK, we'll move, we'll give up our land and our way of life and our communities and our history to come over to this other side.' It didn't happen that way. And they deployed all kind of tactics to try to make that happen," said Lang.

The city cut off services for black people who refused to move and -- if that wasn't enough -- Lang said families were harassed. Their schools were moved to the other side of town, their roads weren't paved, street lights were installed and people even started dumping trash in some of the freedmen communities.

Despite the harsh tactics, not everyone left.

"We cannot come to Clarksville without going to Sweet Home Missionary Baptist Church," Lang said, smiling as she walked toward the all-white building. "The fabric of kind of this idea of hope and resilience stemmed from the church and I think that you know, in the question before, what kept folks going, I'd say the church."

Sweet Home is still in Clarksville today and so is the house Lang's great grandparents lived in.

"I wished that my family still owned this home," she said with a sigh, standing in front of the home.

Lang's family, like so many others, left their freedman community for the East side.

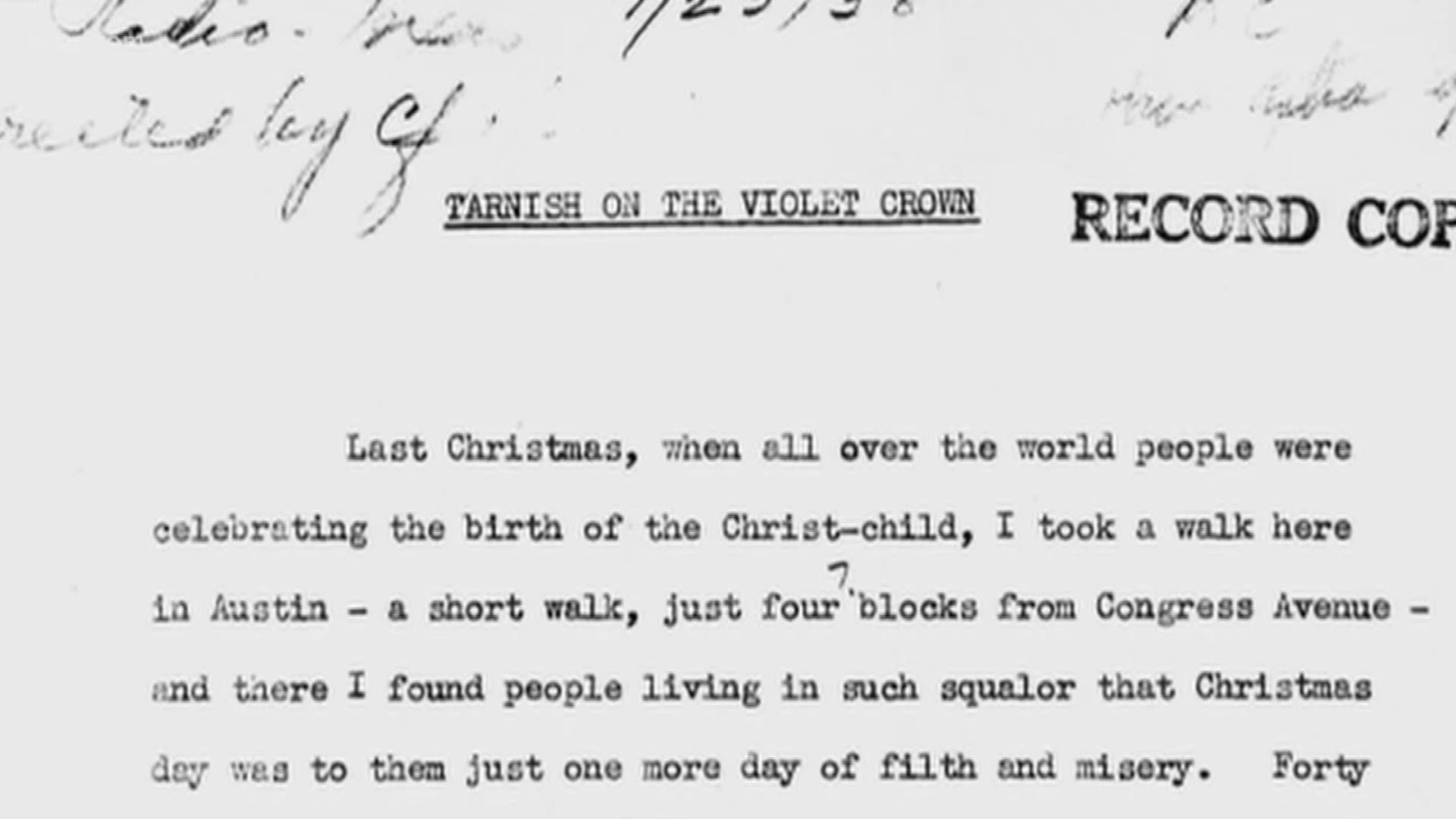

Ten years after the City Plan of 1928, then Congressman Lyndon Baines Johnson penned the "Tarnish on the Violet Crown." It's considered his first major address and was put into the congressional record.

"That address was essentially him talking about walking around Austin on Christmas Day and seeing the absolutely devastating poverty," said Brian McNerney, archivist at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

Johnson fought for fair and affordable housing. As a result, Austin was one of three cities to get the first federally-funded housing projects in the country: Rosewood Courts for Blacks, Santa Rita Courts for Hispanics and Chalmers Courts for Whites.

"Lyndon Johnson appeared before the Austin City Council on Dec. 27, 1938 and addressed them about the project. You know, about these three projects, and his determination to get the ball rolling and that this would be the beginning," said McNerney.

In his final days as president, Johnson came back to Austin for the groundbreaking of the Austin Oaks housing project which was a result of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The act banned housing discrimination.

"In the 188 years of our government, I would list the Housing Act of 1968 as one of the 10 most important," Johnson said in his address.

"This act provides the machinery and the inducements and the incentives to build, not in the next 30 years -- but in the next 10 years -- 26 million housing units," he added.

Through the years, as Austin changed and grew, its black community largely remained on the east side, building a strong sense of community. But residents said crime was a problem and there was a lack of city resources.

"I remember my family's church and other churches saying, 'What can we do?' Let us try to create some resources and businesses to revitalize East Austin," said Lang. "And the city denied that. You know that was not something that happened. And then it was like things people were fighting for them to do never happened until it was time to gentrify."

Just like today, people continued to flock to Austin and the housing stock couldn't keep up. So developers started building east. Those new developments raised property values and high property taxes stifled homeowners, leading many to sell their homes to developers who would build more new homes and businesses, gentrifying the neighborhoods.

RELATED:

"The irony of you force everybody to come over here and now they're being forced out of here," said Lang.

While gentrification hit Austin's black community first, experts said it's only starting there.

"It's a bell weather for issues of affordable housing and displacement for all Austinites. It's really a trend that you see in every neighborhood," said Eric Tang, PhD, who teaches African American studies at UT Austin.

City leaders are working to address affordability. This year, the city council formally recognized the damage the 1928 plan caused and Mayor Adler created a gentrification task force.

And a new land development plan is in the works. It's called Code Next. It will greatly impact housing. The process is happening now and everyone in Austin has a chance to weigh in to shape the future of Austin.

RELATED: