A look at historical Austin contributions by Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders

KVUE honors AAPI Heritage Month in part two of our three-part series.

Editor's note: This story is part of a three-part series airing this week. Tune in tonight and Wednesday at 6 for more. For part one, click here. For part three, click here.

In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, we're continuing our series of special reports about the fastest-growing minority segment in Austin.

On Monday, we looked into how the first AAPI's settled in the Capital City and the racism they faced.

On Tuesday, we focused on the contributions and the impact of this community.

Austin's Chinatown

Chinatown Center in Austin is filled with dozens of Asian American and Pacific Islander restaurants and stores.

AAPIs and fellow Austinites have been flocking to the 180,000-square-foot outdoor center since its opening in 2006.

With the exception of 2021 because of the pandemic, the center off Lamar Boulevard is the site of the annual Lunar New Year Celebration – one of the biggest holidays for AAPIs.

The center's developer, Alex Tan, makes sure it's a big to-do, because keeping these traditions alive is important for him.

"It's for the community ... we got to know where we come," Tan said.

He said it's a way for AAPIs living in Austin to remember their cultures, especially since his own path to the U.S. was a complicated one.

Forced out by a violent regime

"And I remember in 1975 when the Khmer Rouge was coming," Tan recalled.

Tan was just a boy when the Khmer Rouge invaded Cambodia, a regime responsible for the genocide of more than 1.7 million people.

"All you hear is the bomb and the shooting and all that," he said.

He remembered how he and his family were forced from their home at gunpoint. In an instant, they lost their house, their business, everything. Barely escaping with their lives.

"I remember when my father, you know, when we get out, my father went and locked the door there and [he] pointed a gun to my father. He said, 'You still want to lock the door. This belongs to the government now.' And my father, like, 'OK, we go,'" Tan said.

The Tans made it out of Cambodia, escaping to Vietnam, and eventually made their way to refugee-friendly France, and then to the U.S.

He isn't the only Austinite with such haunting memories.

"No education, no family, no language, no culture, no country, no mother, no father. Nobody," said Channy Soeur, a fellow Cambodian refugee.

Like Tan, Channy Soeur was forced out of the country by the Khmer Rouge.

At 15 years old, he nearly lost his life defending Cambodia.

"Somebody threw a grenade and exploded next to me and I got hit by both legs and I bled from two o'clock in the morning until about 9 a.m.," Soeur said.

Just one day before the Khmer Rouge took over, Soeur escaped. And thanks to the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975, Soeur said he was one of 130,000 refugees allowed into the U.S.

At the time, he only knew three English words.

"Oh, I know three words real well – yes, no, OK," Soeur said.

Acceptance into the University of Texas brought Soeur to Austin. And after a stint with the City of Austin in the '80s and '90s, he started his own civil engineering firm.

Building representation in Austin

Along the way, Soeur noticed a lack of AAPIs in positions of power.

"We didn't have any Asian American public officials, we didn't have anybody in the management ranking in the city, we didn't have any Asian Americans participate in the commission anywhere. There is no Asian American in the board of directors of anywhere at the time," Soeur said.

That's when Soeur's activism started. He has launched organizations for AAPI business leaders, like the first Asian Chamber of Commerce in Austin.

Soeur is credited as one of the driving forces behind the Asian American Resource Center on Cameron Road.

He's now focusing on another initiative: stopping Asian Hate. It's a vision Austinite Evan Taniguchi shares.

"I think it's really appropriate right now that we talk about this kind of stuff," Taniguchi said.

As the third-generation Japanese American makes his voice heard on social issues, millions have enjoyed his family's contributions for decades.

"So there's a lot of history," Taniguchi said.

Evan Taniguchi is the architect behind one of Austin's most recognizable buildings: the Palmer Events Center near downtown.

His father, Alan, designed one of Austin's most iconic landmarks: the hike and bike trail. And Evan's grandfather, Isamu, designed and built a three-acre garden as a gift to the city for educating his two sons.

"He didn't get paid anything here. In fact, he had to pay for most of the materials himself," Evan said.

After 18 months, and doing most of the work himself, the Isamu Taniguchi Japanese Garden opened in 1969.

Isamu Taniguchi's gift, despite losing his home, business and freedom after World War II, speaks volumes, according to Austin History Center Archivist Ayshea Khan.

"So that we can remember how important it is for us to build solidarity with one another, even through these really painful times in our history," Khan said.

Contributions paving the way for the future

AAPI contributions in Austin are leading the way to the future as well.

"I devoted my life to preserving and maintaining vision," said Dr. Mitchel Wong.

After more than 50 years as an opthalmologist, Dr. Wong is retired, but not before donating more than $20 million to create the Mitchel and Shannon Wong Eye Institute at the Dell Medical School with one of his four sons.

"So by establishing the Department of Opthalmology, this is something that will benefit the city locally, it'll benefit the state," said Dr. Wong.

In 2005, Jennifer Kim made history as Austin's first AAPI to be elected to the city council.

Kim said she's proud to be part of the council that got the Asian American Resource Center up and running, among other accomplishments.

"And so now we have a lot of seniors who get their meals, their children who get their summer camp there. All the great programming. I mean, last time I checked, it was the most it was the busiest parks facility in terms of reservations and bookings," Kim said.

In 2021, Jerry Bauzon also made Austin history when he became Austin's first assistant chief of police of Asian heritage.

"So both of my parents were born in the Philippines," said Bauzon.

He added, "I saw numerous AAPI cadets coming through the academy, graduating and becoming sworn officers. So I was really proud to see that."

But with the surge in hate incidents against the AAPI community, Assistant Chief Bauzon and other community leaders know there are still hurdles to overcome.

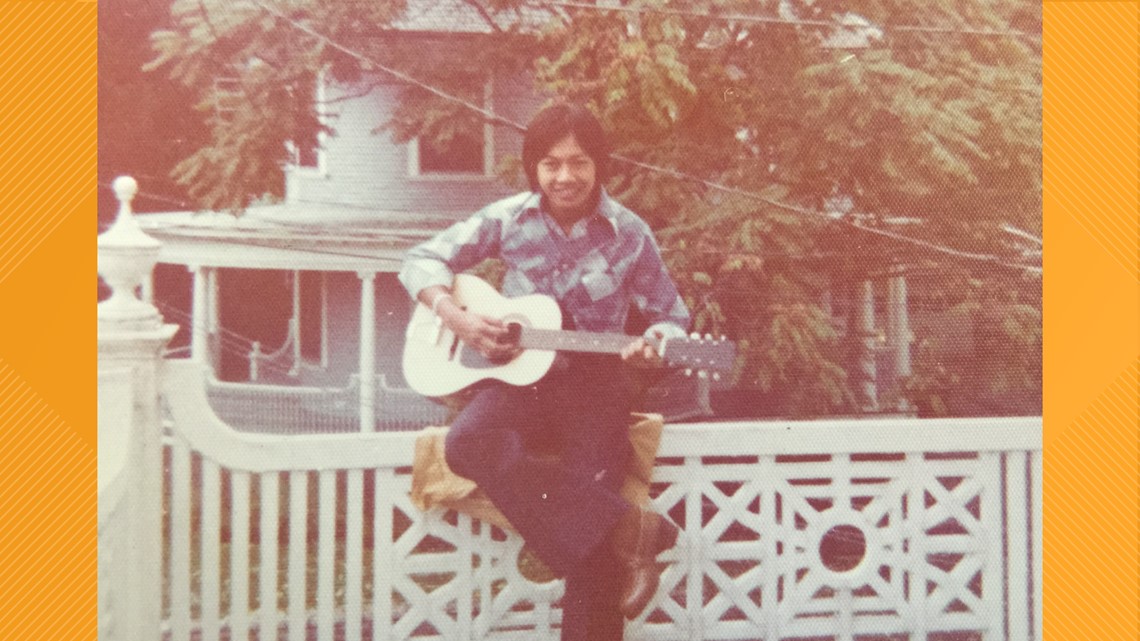

PHOTOS: AAPIs talk history, racism, Austin influence

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: